The Year of Lear

i present to you: Presentism

In academic circles there is a form of historical fallacy whereby a certain kind of interpretation incorporates, or encourages, a comparison of history with similar events in the present, especially on the moral compass. This fallacy is sometimes called “Presentism.” It presumes to cast a shadow of our current ideas upon events in the past.

A typical example of this fallacy is slavery. Today slavery is universally acknowledged as abhorrent, though still practiced by criminals. But there was a time when it was considered by many nations to be the right of a conquering people. Ancient history is jam-packed with such people. The all-too-Christian Spain was well-known for this in the conquering of the New World, as well as of Africa. Certainly this was how the Koran perceives slavery too—from the point of view of the victor.

The same goes for Homer and Epic of Gilgamesh, etc. On the other hand, slavery wasn’t so wonderfully portrayed in the Bible. Why? The point of view was reversed, and mostly that of the conquered: Jews were captured by Syrians or Egyptians; Christians, not exactly slaves, but oft-times prisoners, were captured by Romans.

A Presentist might say, no, no, no. Slavery was BAD even then. Well, certainly the slaves of the time would not disagree, if we could rouse them from their graves and take a vote. But on the other hand, hundreds of years later, those same slaves, or rather their issue, might themselves become conquerors, or at least revolutionaries. In that case, they could do what they will with their own captured prisoners. It was a kind of universal “preference right” of conquering people if you will, as long as the conquerors had enough warriors and priests to enforce the precept.

Thus, depending on the era, you could be a Christian and your ideas about slavery were really not universal—or consistent with Biblical perspectives—but rather attached to those of your social unit and your time in the sweep of history. In some cultures, the life of a slave was superior to having one’s head lopped off and stuck on a pole in a public square. Or being thrown away on an island prison. Or maybe not. It seems to depend on the quality of a particular slave’s life. In the Middle Ages, some European nations began crafting laws allowing for the freeing of slaves and “indentured servants” by their masters, for a variety of virtuous and not so virtuous reasons. These laws coincided with the development of complex judicial systems. They did not exactly attend to “slaves rights” so much as allow for the lawful purchase-out as well as freeing of slaves by masters who did not want to be sued or imprisoned for unjust slave treatment, and usually handled on a one-by-one basis.

James Shapiro “The Year of Lear” (2015)

So where are we going? Back in time to a very strange era indeed, the time of one of my favorite authors, William Shakespeare. I just finished reading a new James Shapiro book, “The Year of Lear” which specifically lands us in 1606 but really takes in the several years preceding and succeeding that particular date.

In the first place, Shapiro’s book has nothing to do with the idea of slavery. But as I tried to explain in my opening paragraphs, when we go back in time, it does take us to a world of assumptions about which we are no longer much accustomed. A world of rules that have since been unlearned. London of 1606 is not an alien world exactly—it is still a world of petty politics, a world of intrigue and treason, a world not unlike our own in some ways—but a world whose moral conqueror’s compass points in a different direction than ours.

Shakespeare is not what I want to share with you this morning. That said, the Shakespeare I know is a lot more accessible than most people think. While I’ve read most of the plays and seen a number of performances and films, I can’t utter the word “Shakespeare” without seeing THE LOOK come over the face of the person I’m talking to. The reason I think most people think that he’s inaccessible is that he’s poetic, and for the people of the 17th century, that may have been more like the frosting on the cake. He knew, as did all the playwrights, that their livelihood depended on entertainment, and he served it up in spades.

To prove that “The Bard” is, first and foremost, entertaining, nothing can substitute for seeing a play in person. Especially by the likes (in Atlanta) of our terrific Shakespeare Tavern, a downtown netherworld where you can eat and drink and fall under the spell of a troupe of fantastic actors who truly know their craft and carefully attend to the audience’s every possible point of confusion. The intent is to make you feel like you get this—and you are back there, of course, in the pit of The Globe, enthralled by tales of princes and kings, intrigues and battles, of captains and maidens, of fairies and slaves and humble servants galore. There are murders aplenty, and comedies aplenty. The theater has balconies and drop floors and aisles wide enough for swashbuckling sword fights. So it is that the actors—in both beards and big bosoms, and colorful period costume—take us tripping into that world, if only for a time.

About Shakespeare himself, hardly anything is known. Much more is known about the London in which he lived. Thus, scholars are apt to write long speculations, in the form of books—like “The Year of Lear”—about what he might have been thinking when he wrote such-and-such a play, or sonnet, or scene, or monologue, or (dear me) couplet. Well, that’s fun too. But Shapiro takes it even further. He immerses the reader in one of the greatest revolutionary intrigues of that century, the Gunpowder Plot uncovered on Nov. 5, 1605, and it’s wide-ranging effects, not only for the speeches in Macbeth, et. al., but for the impact on the average citizen as well.

More tomorrow. It is Saturday in these woods, and the wind howls. It is early and dark out. The yard is dusted with new snow. Our dog sleeps in, as it is 25 degrees out. My fingers are too cold to remain still typing at my desk when palace duties call. It is not, methinks, unlike the “weird sisters” who I just spied, from behind the curtain, visiting Macbeth prophetically:

Fair is foul, and foul is fair;

Hover through the fog and filthy air.

I must to my duties.

Exeunt.

The Gunpowder Plot

So it’s OK if you know nothing about 1606 or the later works of Shakespeare—”Lear” (c.1605), or “Macbeth” (c.1606) or “Antony and Cleopatra” (as yet to be written). Shapiro’s book is just as much about the intrigues of England and King James—and the beliefs of the Protestants the Catholics—and the culture of the theater, and the complaints of the common man—as it is about the great stories of ancient history.

And that is what I’d like to share. The theater was always in trouble, and had been for years. The puritan ethic had been building for many decades and, like Prohibition in this country, there was always a trend toward banning theater entirely. Playwrights were wont to be serving up romances too lascivious, and satires too delicious—if not for their audience, at least for the King and the Church. By force of law, the troupes had to show a degree of discretion. It was all-too-easy to offend—Ben Jonson was not the only writer to be thrown into prison, in his case many times over, for his indiscretions and howling at political stupidity or religious dogma.

So it was the players and troupes walked a fine line that changed each year in response to some law or other in Parliament, or some archly sniffle in the King’s Court. Their fortunes rose and fell at the Parliament’s and the King’s whim. The troupes were immensely popular among the average Englishmen, and they not only played London audiences, but toured England and Scotland aplenty—especially the case when bouts of the Plague scourged London and the theaters were temporarily shuttered—sometimes for months. The theater was the radio play, the movie house, and the weeknight TV thrown into one. On the other hand: Sermons, Proclamations and (on occasion) Broadsides were their Fox News. When needed, couriers on horseback were the “wire-copy” keenly awaited.

There was a hunger for facts, even if “news”—word-of-mouth, for the most part, as newspapers had not evolved into being—was borne on the back of gossip and rumor, to an even greater degree than today’s Twitter. Facts were harder to come by back then, but eagerly lapped up. Still the common man was as likely to clothe his facts in a suit of superstition as in a suit of armor. He believed in ghosts and evil spirits, and God and the Devil, as surely as he did the English warship.

You can see I do not have in mind an Elizabethan England as a kind of idyll encouraged by films like “Shakespeare in Love” (which, by the way, is a fiction, but I do love). In actuality it was a fearful place for some. It is a tribute to the long-living Queen that we still think of the first Jacobean (post-Elizabeth) years as somewhat Elizabethan. Her influence on the culture was all-embracing, and for a time she had the backing of the population, but nonetheless Kings and Queens were always subject to possible overthrow, and had to be mindful of such. They (and their courtiers) drew up laws that today seem Draconian, but were probably needful if they intended to keep their heads along with their crowns.

King James ascended to the throne of England in 1603 upon Elizabeth’s death. His regency was noted in the early years as one leaning toward international accord. Eventually we would know him as a scholar and provider of the great Biblical translation, and though getting a late start, ships would soon be departing establishing Jamestown as the first permanent English settlement in the New World. His mission, also, was Unification of the Kingdoms. Really a pie-in-the-sky idea at the time. A sort of, ahem, liberalism.

In his world, though, the Protestants ruled. They were intransigent and intolerant enough, but the Puritan element was, if you will, their “right wing”. Theater and drink was not enough for their bile. They had, in their sights, Catholics. Being a Catholic per se was not a crime, but it was—hard to believe—illegal to practice the Catholic religion. Obviously people believed deeply in the religion they were born into. The relics of communion were hidden away. Jesuit priests were smuggled into England and occasionally disguised or closeted away in “hiding holes”—this is, by the way, four decades before the Puritans took over England under “Lord Protector” Oliver Cromwell in 1649.

So James was was not only a Scot, and King already, but as a consequence, a Protestant through-and-through. In that way he represented a real threat to the Catholics, and the seriousness with which Catholics were taking this threat was unknown to the authorities. Of course the antipathy went both ways. The Protestants had become incensed by a particularly galling policy the Catholics and their Jesuit priests had come up with to help avoid prosecutions. It was known (officially by both sides) as “equivocation”, the practice of answering questions at a religious inquest either not quite fully, or ingenuously, so as to avoid punishment. There were several varieties of it, and treatises written on it. One type was called “mental reservation”:

This sort of equivocation meant saying, for example, “I didn’t see Father Gerard . . .” while finishing the sentence in your head with the words “hide himself in a well-concealed priest’s hole.” It wasn’t a lie, exactly, if you believed that God knew your thoughts, even if the person questioning you could not.

Shakespeare, knowing his audience was hungry for contemporary allusions, ingeniously and famously worked equivocation into “Macbeth,” a play where hardly anyone says anything that isn’t misleading. All shades and stripes of his audience were keenly thrilled.

As the few years went by since the coronation of the King, gradually things only worsened for the Catholics, especially in the way of law enforcement tactics which had attempted to rout out the “poison” of equivocation. Plots had been uncovered in Elizabeth’s time as well. A sort of war had begun being waged, both above and below ground if you will, and it came suddenly and horrifically into light at the end of October of 1605. A certain Lord Monteagle, who had previously renounced his Catholicism following some previous plots, had received a secret letter warning him to be out of London on Nov. 5, the first day of the convening of Parliament that season. To make a long story short, the authorities uncovered a stash of barrels of gunpowder in a great vault underneath Parliament.

Thus the Gunpowder Plot was multi-pronged. There were discovered enough explosives to blow up Parliament, and to kill everyone in it. A secondary plot was to kidnap the King’s daughter Elizabeth, in a town not far from where Shakespeare lived, Stratford-Upon-Avon. And this plot was actually attempted, the kidnappers found out, and eventually dragged from their hideouts.

Months passed as the prosecution of the accused, including Guy Fawkes, went forth through the courts. The punishments went “beyond Guantanamo,” beyond no-defense-lawyers, beyond interrogation and mere torture. In May, Guy Fawkes and all the “recusants” as they were known stood up in court, unrepentant, and pled not guilty. They were subjected to what follows, and what must seem to rival the wrath of God and the fires of hell itself. First they were dragged on the street by horses to the place of execution. And here Shapiro summarizes, citing several quotes from attorney general Sir Edward Coke’s description:

. . . each traitor was to be hanged, then cut down before strangling to death. While still alive, he was then “to have his privy parts cut off and burned before his face” and his bowels “taken out and burned,” before his head would be “cut off”. Lastly his body was to “be quartered, and the quarters set up in some high and eminent place, to the view and detestation of men and to become a prey for the fowls of the air.”

In the countryside, where the kidnappers were killed—but inadvertently buried—their bodies were dug up and their heads were hung on poles strategically placed about the neighboring towns.

Recusant Sir Everard Digby, was:

. . . eloquent to the end. After asking forgiveness he prayed quietly for a quarter hour, “often bowing his head to the ground,” before ascending the scaffold. He was only hanged for a very short while before being cut down and butchered. It was said that when the executioner plucked out his heart and exclaimed to the crowd, “Here is the heart of a traitor,” Digby in his dying breath cried out “Thou liest!” True or not, it was reported that common folk gathered there “marveled at his fortitude” and talked “almost of nothing else.”

Be not a Presentist, my friends! This was a Godly cruelty, and London was the stage for it. But that was not the end. The pressure on the Catholics only grew. The Puritans saw their opening, and went—over time, over the next few decades actually—for the jugular.

Unlike our 9-11, the Gunpowder Plot was an event that did not actually happen, though it was going to, and it would have, if only a naive sentimental Catholic had not tried to warn his friend. Was this not divine wrath on a scale of the great Khan?

If the plot had come to pass, life would not have been the same. A hell-bent civil war seems likely. And would Shakespeare have written Macbeth? The thought leaves us wondering if life in the New World might have tilted. Would Jamestown have become Spanish after all?

Today our nation and voters look back to an era when “America was great.” Curiously a similar nostalgia came over people for the reign of Elizabeth a few years after the plot—when rules tightened, and censors led a the charge against profanity and godlessness in the public theaters. There was a growing nostalgia for the reign of Queen Elizabeth, which was a time of imperialism abroad, victory over the great Spanish Armada, etc. James did not get his much longed-for United Kingdom, fighting Parliament over an issue that had failed for centuries. But it would come, eventually—unification that is—and with the barbs of Catholicism fully in tact.

A final note

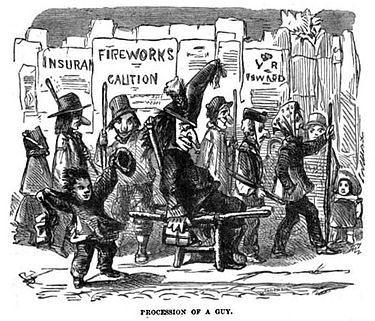

“Guy” was short for Guido, a name Fawkes had taken on while fighting the Spanish. This is actually the source of the name “guy” in English—yes, the one that we use today—which more directly descends from the tradition of children toting a “guy” figure around town on “Guy Fawkes Night”—a stupendously ugly character of evil intent, held up on sticks and dressed as a street person in long hair and tatters. Guy Fawkes’ Night was an event celebrated by bonfires and fireworks. Over time the word “guy” took on the meaning of “oddly dressed person”. It’s still with us today. Oddly enough.

Leave a Reply