Montezuma’s Sweet Revenge

Montezuma meets Cortés in this painting from the “Conquest of Mexico”

Unknown artist, c.1660, Kislak Collection, Library of Congress, Painting 3 of 8

On November 8, 1519, two warriors, utterly unknown to each other, faced off in solemn greeting and mutual distrust. At the time neither of them could fully grasp the consequences, but their names would one day make history: Montezuma II, emperor of the Aztecs, and Hernán Cortés, Spanish conquistador.

Over a period of weeks and months “the Meeting,” as it has come to be called, devolved into a desperate collision between two alien cultures—literally two superpowers from opposite ends of the earth. While each side may have felt some curiosity, some itch of fascination, within two years a ghastly war would ignite, consuming tens of thousands of lives, innocent and otherwise.

Next year will mark the 500th anniversary. A miniseries is in the making. Javier Bardem wants to play Cortés. Steven Spielberg has said he will direct. Originally a movie script by Dalton Trumbo, Amazon Prime is angling to bring it on as a miniseries. What could go wrong?

The unknown factor, that’s what: Montezuma himself—now, as throughout history, the ghostly enigma, the legendary question mark. Who was he really?

Here’s hoping they don’t screw it up.

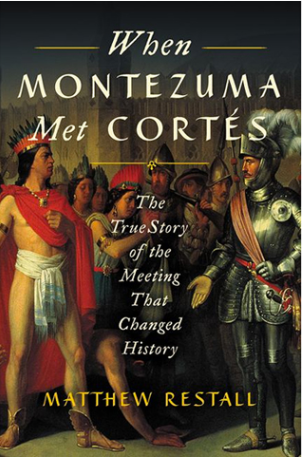

MATTHEW RESTALL

“WHEN MONTEZUMA MET CORTEZ” (2018)

The Spanish had stumbled upon the Indies just twenty-seven years before the Meeting. But it is fair to say that things had begun to stall out for the Crown. Was the discovery of a new world getting to be old news?

Today we might say the return on investment was not yet close to its advertised potential. Sure, the Spanish had finally taken control of the ports of Cuba. Sure, they were seeking real estate, booty and precious metal in every nook and cranny of the Caribbean. And sure, they had discovered not just one, but many “new worlds” to the amazement of Europe.

Today we might say the return on investment was not yet close to its advertised potential. Sure, the Spanish had finally taken control of the ports of Cuba. Sure, they were seeking real estate, booty and precious metal in every nook and cranny of the Caribbean. And sure, they had discovered not just one, but many “new worlds” to the amazement of Europe.

It’s just that, due west, there was a mysterious land said to be teeming with gold and silver, a realm of sparkling gems and sea-green turquoise. In its midst was a fabled city built on lakes, of all things, with fearless warriors who secured the frontiers. This continent, if indeed it was a continent, was all the buzz among the natives of the Caribbean.

Curiously, however, the new landmass remained virtually unexplored by 1519. Those same conquerors who had arrived triumphantly on great ships, who had clad themselves in armor, and who rode horses—what the natives called “people-bearing deer”—yes, those warriors had somehow come up short. What was the problem? It might’ve had something to do with Diego Velázquez, a man who held not one job but two: Governor of Cuba and the colonial adelantado, “holder of the conquest license.” Velázquez had already authorized, organized and outfitted a couple of underfunded expeditions to the Mesoamerican mainland. Each one of them had turned out badly.

Back home in Spain the throne was getting antsy, and for that reason, the adelantado desperately needed a win. But deep in the forests of the outlying Caribbean colonies, the truth of the matter was becoming evident. In the hinterlands, the Spanish were under attack.

Hernán Cortés

Furthermore, there was no conquering hero at the ready. In fact, the task of making a successful landfall to the west fell to an upstart: a brash 34-year-old Captain Cortés. Sailing from Havana, his shortest route would be across the Caribbean to the Yucatan peninsula. But his outfit was meager. He arrived in thirteen lesser vessels. His contingent of roughly 300 soldiers, 100 slaves, a small supply of cannons and 13 horses was not exactly overwhelming.

Lacking any significant military intel, Cortés could not possibly know what awaited him. Outmanned and not well provisioned, this brash young leader was nonetheless possessed of something far more useful: a crafty military mind. Officially he was simply to strive for a successful landfall, cut his way through mountains and alien territory, sweep inland and map and explore all that he could. Privately, he seems to have modified the plans a bit.

Sensing intrigue, Velázquez tried in vain to cancel the voyage. But Cortés was two steps ahead. He landed in Yucatan with his own conquest mission in mind. Eventually he would commandeer local tribes, he would make pacts with unhappy allies, he would bribe or intimidate—even torture or kill—any enemies that crossed his path.

The Aztecs had already heard tell of the bearded, light-skinned conquerors. The leaders had gleaned a good bit about what might be coming through scouting reports. It appears that preparations were already underway at the Great Temple Pyramid in the heart of their cherished capital city, Tenochtitlán (pronounced “ten-OHSH-tit-LAHN”).

By their own estimation, the Aztecs were top dog. The Aztec people called themselves “the Mexica” (meh-SHEEKA), and in their stories of origin they had arrived in the high plateau as if it were a promised land. They felt a connection to rulers of a former time, the Toltec, with whom they shared a “pantheon of divine forces” that ruled over everyday life. Like the Maya and the Inca, the Aztec culture was infused with art, sculpture, and architectural wonders. Their books were painted on deerskin, bark, and maguey paper. And just as in the ancient history of other advanced cultures—yes, even the Chinese and the Greek—they appeased their god or gods with human sacrifice. Their society was based on agriculture. Their union was forged from a loose knit structure of farm workers, commoners, artisans, merchants, traders, nobles, teachers, warriors and priests.

Certainly in Central America in 1500 they were the advanced civilization. Over the previous two hundred years they had carved out a jewel of a city, enjoyed a metropolitan culture, ruled both allies and enemies with an iron fist for decades. Supremely confident in their achievements and military prowess, they had even forged a “Triple Alliance” with two surrounding city-states. They believed their world was utterly impregnable—nestled between two volcanoes, bounded by mountain ranges, and trenched off from invaders behind a maze of lakes and fortifications.

But dire prophecies hung in the air. The high priests and astrologers had serious misgivings. For ten years running, oracles had been predicting the “end of days” based on celestial events. There were comets, said to be apocalyptic. A fire across the sky had boiled water in the lakes. Magical snakes and other beings had been reported, visions of men with two heads—and on and on. Many wondered what earth-shattering event awaited them just over the horizon.

As if that weren’t enough, there may have been a particularly salient prophecy. The Aztecs especially revered Quetzalcoatl, “feathered serpent,” god of wind and  wisdom. Tradition also held that two hundred years in the past a great Toltec priest-king, Topiltzin, chose to become “Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl,” essentially declaring himself to be the earthly incarnation of the beloved god. He brought peace and prosperity to his reign. And when an uprising forced Topiltzin to flee to the east, the legendary king promised one day to return.

wisdom. Tradition also held that two hundred years in the past a great Toltec priest-king, Topiltzin, chose to become “Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl,” essentially declaring himself to be the earthly incarnation of the beloved god. He brought peace and prosperity to his reign. And when an uprising forced Topiltzin to flee to the east, the legendary king promised one day to return.

It was a weighty prophecy, one that hung over the head of this King of the Aztecs who ascended the throne at age 34 in the year 1502. Scholarly transliterations have never quite agreed whether “Motecuhzoma” or “Moctezuma” or “Moteçuma” should be used—spellings that have been derived from both pictographic writing and the spoken language Nahuatl. For us, spelling and pronunciation is not at issue. It is the man, the mystery, who in our era is widely known by the name Montezuma.

The Spanish would hear much of him. The Aztecs would say, proudly, that he had 300 servants, 44 conquests, and 200 wives. He was also reputed to be wise, a philosopher-king.

But by 1519 rebellions had been on the rise for the Aztecs. Unrest and yearly wars were not uncommon. The human sacrifice thing was getting a bit out of hand, and the kingdom was under assault from many quarters. What to make of signs from on high? Was ancient prophecy at long last upon them?

The Plan. In those glorious days of old, conquest was in the air. But so was wonderment. Tales of weird and alien peoples, inhabiting these strange new worlds, were all the rage.

Velázquez implored Cortés to determine the truth behind reports “that there are people with broad and massive ears, and others who have faces like dogs,” and to find out “where the Amazon women are.” – Restall, p. 78

The single-minded Cortés frankly couldn’t be bothered. His luck had turned, and his focus shifted entirely to the conquest ahead, the gold and the glory.

Now … do what, Diego? Poke around for Amazons? Surely you jest?

On his now-infamous march to the Aztec capital, Cortés ingeniously made himself out to be whatever the occasion called for: a diplomat, a partner in detente, an uncompromising victor. While he hadn’t the resources to seize land or take control, he made a great show of swords and gunpowder and he eagerly offered to make pacts and treaties with local tribes. He acted as both confederate and victor, even riding horseback into the lesser city of Tlaxcallan as if it were ancient Rome, in triumphal style. He showed off the power of his cannons. He raised an army of local tribes resentful of the Mexica. Near the end of his journey, he even callously massacred something like four thousand civilians in Cholula, whom he said were ready to rise up against him.

Cortés’ trajectory was set, his time was now, his path forward uncompromising. The reward, if he succeeded, would be to pierce the defenses of the heavily fortified Tenochtitlán, the locus of Aztec wealth, as bustling and densely populated a city as ever there was—compared by some contemporary writers to the Paris of their day.

The Meeting took place 27 years and 27 days after Columbus first set foot on American soil. This surprising confrontation turned out to be … well, actually, we don’t know for sure: a surrender? a deception? a Mexican standoff?—it depends on who you believe. In recent years a variety of questionable accounts and contradictory details have been gathering like clouds that now dot the historical horizon.

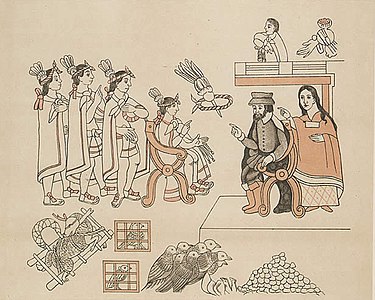

The Meeting, with Cortés in charge.

But assuming it happened as Cortés said it did—facing each other across the timeline of history—each man was no doubt mulling his options. Cortés, fresh from his military victories on his march to Tenochtitlán, would likely have cast about for clues on how to make his next move. Montezuma certainly would not have blinked, but no doubt weighed his uncertain future. Malinche, the native woman captured by the Spanish—who to this day is revered by people of Mexico as Doña Marina—assisted in translation, speaking Mayan as well as the Aztec language, Nahuatl.

Conflicting tales are numerous. Even of that initial greeting, we have more than one account. Cortés claimed that he reached for the hand of the emperor, which was accepted. Another story has Montezuma, or one of his attendants, refusing the courtesy, with Cortés privately taking umbrage.

Yes, even the cameo of welcome is suspect. What historians are up against is revealed in just that scene: they really don’t know the truth, either about that encounter or about others.

The Meeting with Montezuma in charge. A modern version containing styles and icons from the era.

But we do know this. Montezuma certainly had them outnumbered. We also know that Cortés later bragged that he had found in the king a weakened spirit, and a surprisingly uncertain and submissive air.

Captain Cortés viewed his destiny through the eyes of God and history. His mission was biblical. He took but a few months to make his way to the promised land, and once there, molded the outcome with his own hands. Upon meeting Montezuma, he wrote, the emperor immediately proffered surrender. In this telling, Cortez accepted graciously, and took rooms at the Royal Palace—a miraculous coup! Montezuma’s confession was penned in Spanish and promptly notarized. Not a drop of Aztec blood had spilled.

But too many questions have arisen over time, and there are no solid historical answers. Did Montezuma actually offer Cortés a number of rooms at the palace? Did he believe, as Cortés maintained, that the bearded visitors were the reincarnation of Quetzalcoatl? Is that really why the conquistadors were allowed to march unharmed into the city? Historians dig into alternate explanations, linguists probe their pictographic texts, archeologists comb and sift every grain of Mesoamerican sand.

The Retelling. To the victor, belong the spoils—and the narrative, of course.

The Spanish later claimed that they controlled the city after the surrender of Montezuma. But as Restall points out from primary sources, the conquistadors had no contact with the native population and little or none with the invading tribes they claim came in with them. Montezuma, in Restall’s account, may well have housed these odd but dangerously armed creatures in the confines of his famous zoo, which was close to the palace, and which contained not only animals from all over the continent but slaves and natives from far flung territories—who, interestingly, the Aztecs considered to be “specimens.”

Whatever the case, we have a hole in the historical record that defies explanation. Historians are now racking up bits of sociological and anthropological evidence to support theories that have a more realistic bite. Restall himself speculates that Montezuma was biding his time, isolating the intruders while trying to figure a way out of a dilemma posed by conflicting military and priestly advice.

Of course we “know” about Montezuma’s supposed surrender but only because Cortés himself said as much—several months later. It was written in his famous “Second Letter to the King”—a somewhat trumped-up version of a victory that had not even occurred yet. Sure, we do know who eventually “won the war”—or, perhaps we should say, the two-year holocaust between the Virtuous Christian Spaniards and the Brazenly Savage Aztecs. After all, such would have been in the headlines had tabloids been invented.

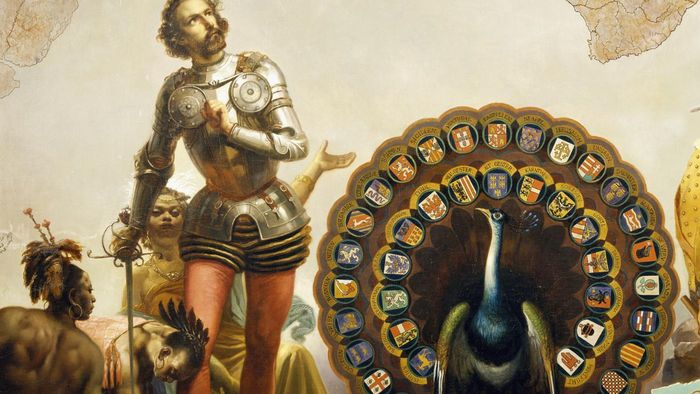

To put it bluntly, Cortés was not a man for all seasons. He is well known to us, even in the modern era: a braggart, a “self-made” tempestuous tyrant prone to ill-advised outbursts, convenient lies, and bloviating self-promotion. Sound familiar? Let’s just chalk it up to the wiles of salesmanship.

Cortés, pacing under a map of the world, takes charge as the natives bow down before him.

In time, the isolated Cortés fled to Veracruz upon fearing that Velázquez had responded with, not reinforcements, but an army sent to arrest and capture Cortés himself. He was right. But somehow, arriving at the coast, the wiley captain convinced the newly arrived contingent from Cuba not to jail him for insubordination, but rather to join him in retaking the city of Tenochtitlán. If there is a genius to be discovered in Cortés, it is this: the Art of the Deal.

The Untelling. Opposing views, even if it takes centuries, do eventually emerge in bits and pieces. But thus arise more questions. Why did Montezuma not have all the Spaniards killed, sacrificed and flayed on the altar of the temple? How could it happen that the stoic, militaristic regime of the Aztecs would surrender immediately, as Cortés later claimed? Was Montezuma duped by the Spaniards into thinking his people were against him?

The arch nemesis, Montezuma, is a mystery. What to make of him? Historians tend to be circumspect, for quite frankly the evidence is scant.

The idealized king,

circa 1600

Certainly Montezuma was not the irascible flesh-and-blood tyrant that Cortés turned out to be. The problem is that the man Montezuma appears to be lost in the clouds of Cortés’ narrative. Many artistic renderings of him are what most historians today regard as fanciful.

Restall offers that Montezuma was playing a waiting game, sensing the military advantage of the Spanish. But for amateur sleuths of history, like ourselves, Montezuma is now and might always be the stuff of legend. Legends are made, not lived. Artists over the centuries piled on, and helped sculpt the image, but in truth they knew only that this emperor comported himself regally, that his ceremonial dress included many-feathered robes, that he “led” his warriors bravely into battle, year after year after year.

Thus, sadly, as a man Montezuma is not even as well known to us as, say, Genghis Khan. Whatever writers and artists and songsters have chosen to say about him, has, over the centuries, been spun from an aura of his tragic vincibility. We too sense this after hearing the tale. Montezuma probably knew the Aztecs could not possibly survive an all-out assault. But we have no letters to prove it, no real signatures, no authorized or even unauthorized biographies. We have only the word of Hernán Cortés, and some secondary and tertiary sources used by the Franciscans.

The Mystery of THE Mythistory

In fact, it may not matter whether there was, or wasn’t, a surrender. What we do know is that two years later, in 1521, there was a fierce battle for Tenochtitlán, followed by a bloodbath of historic proportions.

The devil is in the retelling. Stories accumulate. Day after day, year after year, decade after decade, at first one story validating the next, and from there accruing into modest, wholesale histories, eventually evolving into massive tomes. Retellings come alive with artistic embellishment, newer versions follow from newly discovered evidence. Word-of-mouth becomes a letter, letters become reports, reportage becomes a history—and in time, the great events in history become poetry, poems become dramas, dramas become panoramic paintings and folk songs and statuary … and movies. Not to mention, in our day, trinkets at cruise line destinations.

So what happens next, myth or history? Matthew Restall has a salient question of his own:

Why did the mythistory of the Meeting as Surrender quickly grow deep roots and continue to flourish for half a millennium? Restall, p.54

Let’s start by breaking down this term mythistory, as used by Restall—at first a real head-scratcher for me.

Matthew Restall

I found it defined only after looking in the “Oxford English Dictionary,” where it is succinctly described as “history mixed with myth; a mythologized version of history.” It derives from the post-classical Latin word mythistoria, which is to say fabulous history.

Another historian, reviewing Restall’s book, identified the term as being first used in modern historiography by Dennis Tedlock, translator of the Mayan holy book of creation, “Popul Vu” (1985).

According to Tedlock, the pre-Hispanic epics are “mythistories” because they make no distinction between the factual and the legendary; their function is not to shore up what Westerners define as historical truth, but to supply a foundational narrative that helps a group of people form a collective identity.

– Álvaro Enrigue “The Curse of Cortés” in the New York Review of Books (May 24, 2018)

Around the same time Tedlock was writing, another historian, Robert William McNeill, presented a presidential address to the American Historical Association, entitled “Mythistory.” In his presentation, he sets out to define the concept intellectually, as a way to account for how belief systems can construct a history from both closely held cultural values, and also the subsequent coloring of the facts by myth.

One person’s truth is another’s myth … myths are, after all, self-validating … The price of this achievement is the elastic, inexact character of truth, and especially of truths about human conduct. Effective common action can rest on quite fantastic beliefs … even become a criterion for group membership, requiring initiates to surrender their critical faculties as a sign of full commitment to the common cause.

– Robert William McNeill, “Mythistory and Other Essays” (1986)

The Making of a Legend

Restall refers to “the many Montezumas,” his “multifaceted afterlife,” and his several “posthumous personalities.” In a way, Montezuma was fortunate not to stand witness at the destruction of this, his only world, which of course came to a sudden end with the obliteration of his famous city.

It is as if Montezuma appears as both myth and historical personage all rolled into one big fat enchilada. Certainly to later generations he is a kind of make-your-own hero (or anti-hero) based on whatever ingredients are at hand.

Over the first hundred years of Spanish hegemony, Montezuma was described as either a hero or a coward. If nothing else, gradually he has become respectable. For all we know, he might have remained in power. He might never have surrendered. He appears not to have raised the alarm, or fought back—but he might have had good reason not to kill or jail the Spaniards. As of this writing, all bets are off. Still, educated speculation can be fascinating. It is mostly the pleasure of reading Restall’s book.

An illustration of Montezuma from the Italian edition of Solis’s History of the Conquest of Mexico (1684)

But we do have some facts. Montezuma died in 1521, about 3-4 months before the final Spanish assault, just before Cortés came roaring back to Tenochtitlán with reinforcements from Cuba. Montezuma’s younger brother ascended to the throne.

And that’s it, there’s your facts. As to how Montezuma died, pick a card: suicide, regicide, inside job, a Spanish-assisted assassination, or perhaps some combination thereof. There are stories to back every scenario. The one story most often repeated has him jailed by the Spaniards in a tower during an uprising in the city. As he emerges from the tower to calm the crowd, he is fatally wounded by a projectile. But … was it by his own people, or by the Spaniards? The Spaniards insisted it was his own people.

You would have to say that the folklore of this dude has been his eternal flame. In that regard we have mostly artists to thank.

Epic Poems

There were many poems written for Cortes, not so many for Montezuma. But the first epic begins in earnest with Spanish poet Gabriel Lasso de la Vega in the 1590s, who promoted the legend of the Aztec king in two epic poems. His efforts went hand-in-hand with attempts by other writers to build an edifice to the character of Indians in general, as valiant fighters and skillful at arms.

Opera

Opera today is an art form aimed at the few. But for centuries opera was the hip concert of its day, outlandish, often preposterous, always entertaining. And … perhaps the best art form for an otherwise unknown Montezuma to assume a truly regal and courageous standing.

John Dryden’s “The Indian Emperour” (1665), the earliest of sympathetic renderings, casts Montezuma as tragic star in the heavens. The Conquest was the setting, still a popular topic even after a century and a half since the Mesoamerican invasion. And in Dryden’s world, Montezuma is every bit a tragic hero, if for no other reason than tragedy was a kind of salvation to the audiences of the era. In this sense “The Indian Emperour” (1665) does not disappoint, and a somewhat believably Shakespearean Montezuma emerges. Having been taken prisoner, the former king chooses to take his own life in lieu of a less honorable end.

Kings and their Crowns have but one Destiny:

Power is their life, when that expires they dye.

Tis now a torture worse than all I bore:

I’le not be brib’d to suffer Life, but dye

In spight of your mistaken Clemency.

…

The Shame continues when the Pain is gone:

But I’m a King while this is in my Hand,—[his sword].

He wants no subjects who can Death Command … – Restall p.104

Vivaldi’s “Motezuma” (1733)

Between 1700 and 1900 no less than ten well-known operas are listed online with the title “Motezuma” or “Montezuma.” Among those I must mention is Antonio Vivaldi’s “Motezuma” (1733)—an odd work but nevertheless one of classical plot proportions (Montezuma is also the father of a daughter in a star-crossed relationship). Still, as you can see in the portrait to the left, perhaps this more regal Montezuma had finally taken the next step to eternal respectability.

Another curiosity in this category is Roger Sessions’ “Montezuma” (1964), musically an old-fashioned, hearty offering, but probably best known to hard core afficionados for upgrading its social sensitivity and inclusion of lyrics written in Nahuatl, as well as Spanish, Latin and French. Hats off to the era of multicultural performance.

Art

There are many, many paintings and sculptures of the invasion, the massacre, and the reconstruction, a few of which I have included with this post. But for the sake of brevity and curiosity, let us add two interesting examples that illustrate the evolution of the Montezuma legend: one from the conquering-happy nineteenth century, another from the revisionist-revolutionary twentieth.

The first work shown below is straight out of the mid-19th century, where a noble and superior Cortés receives the surrender of a somewhat chastened Montezuma—this is the classic tale.

In the second work, from the mid-20th, a very modern reframing of the Spanish arrival depicts a twisted Cortés in league with the Church fathers for enslaving the people of Mesoamerica.

Constantino Brumidi “Scene 3: Cortés and Montezuma” (1859)

From the Frieze of American History in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.

Montezuma surrenders, capitulating to superior force.

Diego Rivera “Disembarkation of the Spanish at Veracruz” (1951)

Montezuma is not to be found here, but Cortés is depicted as a hunchback. Death, hangings, slavery and Franciscan rule plague the land.

Song

Song lives in the space where both truth and myth seem to merge into one. If we today possess an art form that comes to us from ancient times, look at song, where an idealistic medium draws historical truth from somewhere above and beyond.

Such is “Cortez the Killer” (1975) by Neil Young recorded with the band Crazy Horse. Played in that raw, gutsy, unapologetic style, Young brings his talent to bear on an event that was seen then as a horrific calamity visited not just on Montezuma, not just the on Aztecs, but undeservedly upon all the people of New World.

Listen here. (The lyrics begin at about 3:20 in the audio clip, and there is a second stanza.)

He came dancing across the water With his galleons and guns Looking for the new world In that palace in the sun On the shore lay Montezuma With his coca leaves and pearls In his halls he often wandered With the secrets of the world And his subjects gathered around him Like the leaves around a tree In their clothes of many colors For the angry gods to see And the women all were beautiful And the men stood straight and strong They offered life in sacrifice So that others could go on ...

And Now: the Miniseries

So here we are in 2018, and I am so looking forward to finally finding out what Montezuma actually looks like. It’s been a long wait, and honestly I am having my doubts. Still, I hope they can pull it off. I really do. I want to see what this new clutch of artists can do with our man, the Montezuma of olde.

That is my enthusiasm talking. My mind says otherwise. My hunch is that Spielberg and team have no clue about the many choices confronting them. The accepted history of the Meeting and the Aftermath has changed too many times of late. Hollywood, which had once been accustomed to picking an ending willy-nilly—and typically a sunny one—now prefers to bask in the dim shadows of dark corridors and the haze of ambiguity. We the audience now demand it. No more sunny endings, no more tidy, bow-wrapped weepies. Give us subversion and intrigues and reasons to believe the answers will all be revealed, just a little way off in the future, perhaps in the next installment, or if not, in the next season.

A concerning omen has been recently revealed, and you should know about it. The original title—from the script written in 2014 for the proposed feature length movie—was “Montezuma.” The working title has now been replaced by what the studio is calling the simpler “Cortes.” Alas.

For the story, read about it here.

Leave a Reply