Walling Off the Hordes

Mankind’s Many Walled Borders

Bukhara Wall, Uzbekistan

Eight hundred years ago, walled cities were many. Among them we think of Paris and London, Jerusalem and Cairo, Babylon and Rome. But in fact, city walls were once de rigeuer. They were so common throughout world history that they actually number in the hundreds, if you count them up. Hey, even Quebec City, of all places! And don’t forget the Vatican (The Donald didn’t)—even though the holy city was never entirely surrounded by walls anyway. For doubters, see the List of Cities with Defensive Walls.

There are many great examples of the remains of walled cities the world over. Tourists flock to them and stand in awe. Wikipedians construct fact-oodles out of them, though historians seem to yawn. But in our travel-guide quest to see, express awe, and find beauty in such ancient monstrosities, we overlook the fact that they all ooze an eerie ooooh-wheee that says “ugly relic” in Swahili. That is because every wall has been defeated, often many times over. Always, sooner or later. The Manchus were finally able to break through the Great Wall of China in 1644. Yep. Don’t hear much about that these days.

But walled countries? Hmm. I am pretty sure that, until now, the distinction goes but to one: China. It took many centuries to assemble the The Great Wall, which defined that country’s northern border and more or less protected the Chinese for nearly two millenniums from the forays of the Mongol tribes.

The Great Wall of China

Today, the hordes have become, not warriors, but various human encampments fleeing a horrid life of either extreme poverty or unbearable hunger and punishing war. So it is that mankind has revived the old tradition of the wall. And due to that, walling off long stretches of border, or whole countries, is certain to become an industry. There will be money in it, even if the architecture has changed. I wonder if the Chinese might bid on our own little project, and buy the concrete from the Mexicans themselves. Actually the most recent concrete wall that I can think of—across the city of Berlin—lasted but 29 years. Eastern European countries have taken to using high-tech barbed wire in lieu of stone, mud or brick. But is wire a wall?

Of course the easiest way to get through a wall is not to go over it. Ask any hacker—you just need help from the inside. This actually happened in London, precisely 636 years ago. In that year, the hackers were not forgers and ransomers, they were a smarmy mess of overtaxed peasants. It was the Very First Tea Party.

Life Inside The London Wall – Peter Ackroyd’s “Chaucer” (2005)

Though London had been conquered by all sorts of invaders over the centuries, the Wall of London had withstood the test of time by, if nothing else, remaining standing.

The Romans built their Wall on “the land side” of Londinium, i.e. at the northern reach of the city in the first century A.D. Eventually, thanks to those pesky Saxon pirates, the Romans had to extend the wall on the riverside as well. The Wall itself did a commendable job of standing up over the centuries, basically just standing there and watching invaders come and go. It even exchanged landlords. When the Romans moved out, the Saxons moved in. Later in the Middle Ages, the Normans were always around to cause a bit of havoc as well. For some weird reason, England and France both thought they should own each other.

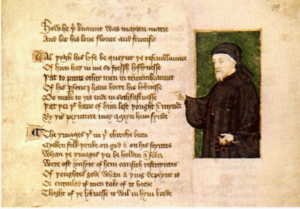

Walls, of course, must be mended. This was done, over and over. And they must have gates. And around those gates they must have neighborhoods—on both sides. You may have heard of Bishopsgate and Cripplegate, the most written-about, but of particular interest to us this morning is the Aldgate, just inside of which was the neighborhood of Geoffrey Chaucer at the time of the Peasant’s Revolt. You see, before he wrote the Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote citations. His title was something like “Customs Official”, meaning the head of the tax office responsible for that particular gate.

Walls, of course, must be mended. This was done, over and over. And they must have gates. And around those gates they must have neighborhoods—on both sides. You may have heard of Bishopsgate and Cripplegate, the most written-about, but of particular interest to us this morning is the Aldgate, just inside of which was the neighborhood of Geoffrey Chaucer at the time of the Peasant’s Revolt. You see, before he wrote the Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote citations. His title was something like “Customs Official”, meaning the head of the tax office responsible for that particular gate.

This was not yet the “modern era” of Shakespeare. Chaucer’s century was near the end of the Middle Ages. By this time England was bound not just by sea, but by a Regency that extended to the utmost of its shores. Richard II, boy king, ascended to the throne at age 11 and was propped up by a massive bureaucracy made up of both aristocracy and landed gentry that ruled by fiat, appointment, and favor. The most amazing thing about this century was the rise of the power of the merchant class and their importance to financing the various kingdoms of Europe. The professional class, of which Chaucer was a member, served the King. It primarily did so in the service of commerce and its many needs for taxes and fees and legal contracts and trade agreements.

Some of the Canterbury tales concern these “new men,” and the pilgrims debate the conflicting claims of noble birth [vs] personal virtue as the guarantors of “gentilesse.” —Ackroyd, p. 29

A mastery of law, contracts, and of rhetoric was needed. It also didn’t hurt that Chaucer, something of a genius and “polyglot” himself, knew Italian and French, which were the languages of court. But English itself was still a poor relation; in London, English substituted for “the vernacular”—yet he chose to write HIS little poems, not in French or Italian, but in his native tongue. This was a first—and he had many years experience at it before he went big-time. He established himself over time as a notable poet of the court.

Though he was not aristocratic, by the 1370’s Chaucer was fast becoming a diplomat of some repute. He kept his official “Customs” position for financial reasons, but he was experienced and much in demand by the King to accompany various envoys abroad, especially in trade negotiations. Several to Europe, indeed to Genoa, led him to an intimate acquaintance with the works of Italian contemporaries such as Dante and Boccaccio—which so influenced his own inclinations: after all, the Divine Comedy was written in “the vernacular”—and the writing of a collection of tales by Boccaccio was proving to be an immensely popular entertainment.

Chaucer inherited the property of his father, and due to that was able to obtain a “career marriage” to Lady Phillipa de Roet. Royal patronages, and a life annuity from the eminent John of Gaunt, followed. Yet for twelve years he remained at Aldgate, looking out for the royal take. He had a nice house, there right near the wall itself. This was a quarter of the city devoted to monasteries and nunneries and the like, as well as official government agencies. But the commercial sector was rising and, with it, new pressures on those who required money to remain afloat.

The Breach

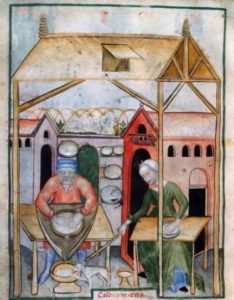

The rise of a dense population on the outskirts of the growing town of London brought with it poverty and crime. In fact, just like today, the unemployed came hand-in-hand with the rise of the merchant class. A growing London also had a rapacious need for masses of peddlers who lived in what we might call the ‘burbs, just outside the walls of the city. It seems so odd now that this burgeoning “life of the city,” as we call it, was forced to advance and retreat each morning and evening, just as it does along the highways of in any great metropolis in today’s world.

The noise of the city began at dawn, when the porter of Aldgate, William Duerhirst, opened the gates. It was the signal for the commercial life of London to begin, with the entry of innumerable pack-horses, carts, wagons and traders on foot bearing eggs and poultry from the suburban farms. A toll was levied on each horse or vehicle, in order to pay for the road leading to Aldgate itself. —Ackroyd, p.58

We know that Chaucer was not aloof from the commoner, from whom he must have had many daily encounters. We know in “The Tales” that he often embellished his beloved middle English with the language of the street. It certainly enabled his comedic style as well. And know we also that he had a window from where he could observe the fearful suburbs—that which we ourselves might call The ‘Hood:

We know that Chaucer was not aloof from the commoner, from whom he must have had many daily encounters. We know in “The Tales” that he often embellished his beloved middle English with the language of the street. It certainly enabled his comedic style as well. And know we also that he had a window from where he could observe the fearful suburbs—that which we ourselves might call The ‘Hood:

From the Eastern window, looking out toward Essex, Chaucer would have known the sprawling and squalid suburb which had grown up beside the wall. Here were cheap lodgings, inns, cook-shops and stalls selling supplies for the the vast army of travelers who made their way in both directions. Chaucer describes such a place with its “hernes” (hidden places) in “The Canon’s Yeoman’s Prologue”:

There was, as in Shakespeare’s day, a certain intolerance (shall we say) for bad behavior. In this pre-Protestant era, however, it was not Puritans but rather “Ricardian” Knights who were the religious reformers, firmly opposed to any effort to reform the church which was the basis of their power. This was well before the Protestant Reformation had reached England, but a certain John Wycliffe was fomenting some craziness of his own.

Yet over the long haul, the financiers and merchants were winning the day. There was an attempt by the crown to fix wage levels of a population seriously reduced by the Great Plague of 1349. Tensions arose with the imposition of a “poll tax” of 3 groats on every individual, rich or poor. A revolt was stirring. A plot was devised. The grumbling was led by a rebellious guy named Wat Tyler. On the day of the massacre, Aldgate itself was covertly opened by an alderman—William Tonge—to allow the rebels access into the city in the wee hours.

They murdered the tax collectors and the most prominent servants of the young king. Geoffrey Chaucer, as collector of customs, was exactly the kind of person the rebels were hunting down. —Ackroyd, p.58

After ceding to some of their demands, the “Peasant Revolt” as it became known was brought to an end by the King’s horsemen who surprised the bunch at Smithfield and beheaded Wat Tyler on the spot. However, just to make sure we have given each side it’s due, one must report that said “Peasants” went most thirstily after just about everyone in a bloody pre-French Revolutionary fervor.

On 13 June, the rebels entered London and, joined by many local townsfolk, attacked the gaols, destroyed the Savoy Palace, set fire to law books and buildings in the Temple, and killed anyone associated with the royal government. The following day, Richard met the rebels at Mile End and acceded to most of their demands, including the abolition of serfdom. Meanwhile, rebels entered the Tower of London, killing the Lord Chancellor and the Lord High Treasurer, whom they found inside. [ . . . ] Their heads were paraded around the city, before being affixed to London Bridge. —Wikipedia “Peasants Revolt”

The rebels had conceived a particular hatred for those foreign merchants in the city who were favoured by the crown and by the tax collectors. On the day after their incursion into Long they besieged thirty-five Flemings who were taking refuge in the church of St. Martin in the Vintry, and removed them by force; it will be remembered that this was the church beside Chaucer’s home…. The merchants and their families were then beheaded in the street and their bodies left to rot. —Ackroyd, p.103

Chaucer survived—luckily for us and for English Literature—but precisely how he escaped, or perhaps simply hid himself somewhere in a secret passageway at Aldgate, will never be known.

The revolt was in a sense a symptom of the final disruption of the feudal system of manorial authority. It represented a break with the past, and was perhaps inevitably accompanied by violence and murder. —Ackroyd, p.99

Chaucer had lived at Aldgate 12 years, but left shortly after the Peasant’s revolt for Kent—which BTW has its own famous wall—thus retiring as a customs official, although he remained in the good graces and lifetime annuity of his sponsor, John of Gault.

Yet by the end of his sojourn at Aldgate he had all the material he needed for the tales told by the Pilgrims in his famous oeuvre. Ackroyd’s book is not a cultural history, but rather a general work that focuses mostly on Chaucer’s poetry and it’s many inspirations. Still, it left me thinking: was this not the beginning of the end of locked city walls?

Epilogue

Perhaps, one day, America will fulfill its own and similar destiny with the much ballyhooed, and soon-to-be infamous, Anti-Immigrant Wall. The wall proposed by Donald Trump and Ted Cruz will be much, much longer and patrolled no doubt by robots with machine guns for arms. It may even extend into the sea. How apropos.

Let’s look far into the future—when Mexican Cartels rule the world—when Austro-Hungarian-Salvadoran tourists clad in sunglasses and bright bikinis will come by to view the remains. The sign will read “Zwarning, Zwatch for Felling Bricke On.”

Within the space of a millennium or two, Americanium will be known as the second great empire to fall to the hordes after a massive fence was truncheoned in the sand. What could be more fitting an epitaph for our land of milk and honey, than the final line of the wonderfully bluesy slave-written spiritual, “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho”. The line will be jack-hammered into the last remaining stones: And the walls came a tumblin’ dooowwwwn.

The countdown clock on it’s demise will commence at the ribbon-cutting. We don’t have to know how the wall will be breached; we need only know that it will be. It kind of makes me think that sociobiologist E.O. Wilson had it right when he proposed that social insects and humans have something seriously in common. I mean, if El Chapo’s guys can do it in a few weeks, why can’t mankind tunnel from Juarez to Albuquerque in a few years? Or better yet, Austin—the future capital of the United States after the current one has been flooded by rising seas?

I have a feeling the hordes will get wise. They won’t need a key. They’ll just go around the wall. Something tells me they’ll start with jet skis. Not long from now, they’ll be arriving by drone.

Leave a Reply