The Great Pandemic

It was the Spanish flu, the Lollapalooza of plagues. It arrived wholly without warning in the closing months of “the war to end all wars.” On the scale of monster epidemics, it ranks as either the biggest or the second-biggest of them all, spanning not just countries, but the world.

The tally of the dead? Roughly 50 to 100 million souls. Only the Black Death of the mid-14th century was possibly worse.

For a few horrific months, the pandemic brought the world to a standstill. The unleashing of the virus was deadlier than the war itself. There was not one but three major waves of flu deaths in 1918-1919, and to many it seemed like world was coming apart at the seams.

Popup Hospitals were set up the world over to treat the victims.

The Spanish flu erupted decades before science cast the beam of electron microscopes upon the mystery. In 1918 we didn’t even know what a virus was. A “flu shot” was developed, based on the mistaken notion that the flu was a bacterial infection. The cure was literally worse than the disease.

Many who contracted the Spanish flu went quickly. Many who did not die suffered mightily. Many were adults, unusual for the typical flu epidemic. Among the nearly-dying were writers who we now extol: Katherine Anne Porter, Franz Kafka, Ezra Pound. Among the dead: French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, aged 38.

In its victims’ honor, some timely new books are about to appear at your local bookseller, accompanied by a documentary or two on television. But is celebrating the right word for this centenary? Let’s just call it a solemn observance.

As we shall see, pandemics humbly remind us that we are first and foremost a species living in the midst of other species.

The LIFE OF a virus

There are thousands of them—SARS, Ebola, Zika, smallpox, yellow fever, the mumps, chicken pox, the common cold—to name just a few of the many viral threats that afflict mankind. But viruses also infect nearly every other life form on the planet, plants as well as animals. They are odd little creatures—and I do mean odd—and I do mean little.

As I read and absorbed the books on this topic, I came to realize that a simplistic understanding of the science might be helpful. So I began to imagine these tiny dudes as parasitic hitchhikers out for a joyride. Upon invading us, they constantly transfer from one cell to another, using each new host cell to replenish and replicate, moving quickly on to the next. Working away like madman squatters, each host cell they temporarily inhabit is pretty much trashed, and often dies.

We learn that our bodies bring on most of our symptoms—an urgent, inborn response to this invasion of the cell-snatchers. The source of our chills and fever and sore throat and mucus and sneezing is, in other words, an escalating war between our immune system and the invading horde. After a number of pitched battles, most of the time our troops pull out a win. But not always. Among the many reasons we might not survive: cellular death of vital organs, and extreme battle fatigue.

Your doctor says she can’t prescribe antibiotics to treat the virus? The reason is that viruses aren’t actually “biotic”—even though viruses are the most abundant “biological entity” on earth.

Unlike standard life forms, viruses have no cells. In fact, most viruses have no DNA, and some have just one strand of RNA, and the RNA is constantly rejiggering its genomic segments (tech term: “reassortment”) in a random process, ultimately resulting in a stronger invasive ability. For this reason, it is believed a virus is one of the smallest forms of evolutionary wiring.

Influenza viruses seem to prefer a constant source of new, unsuspecting victims, and have evolved to fling themselves at outsiders via the microscopic mucus droplets contained in our coughs and sneezes. Not all viruses travel so lightly. Other viruses like it so much inside us that they unpack and bed down for the long hall, taking up residence in less sensitive cells, having evolved to stay the course. Among the latter are unwanted relatives, such as the annoying herpes. Even worse are the life-threatening rogues that just won’t go away, like Hep-C and HIV.

The flu, however, doesn’t stick around. It has one huge advantage. It can infect millions at a time, via the most efficient delivery system imaginable. Which is why when you hang around with a sick person, you get a mouthful of the flu with every breath. The virus actually arrives in your body in the form of infected cells in tiny droplets from their body.

To put this into an aerodynamic context: your next flu infection will most likely be delivered directly to your nasal doorstep by a hefty blow from someone you know, or even some stranger in close proximity. It will arrive in the form of a micro-mucus shower flung at you between 50 mph (coughing) or 400 mph (sneezing). Which is to say, it is pinpoint effective over a distance of about two meters. (Statistics courtesy Jason Socrates Bardi in his article “The Gross Science of a Cough and a Sneeze”).

DAVID QUAMMEN “SPILLOVER” (2010)

Science writer and naturalist David Quammen struck gold with his award-winning book “Spillover” back in 2010. Framed in chapters highlighting the many discoveries of each selected viral or bacterial disease, mostly from the 20th century, he composed a sort of symphony of growing scientific knowledge based on interviews and first-person accounts of the medical researchers themselves.

Science writer and naturalist David Quammen struck gold with his award-winning book “Spillover” back in 2010. Framed in chapters highlighting the many discoveries of each selected viral or bacterial disease, mostly from the 20th century, he composed a sort of symphony of growing scientific knowledge based on interviews and first-person accounts of the medical researchers themselves.

“Spillover” is a non-technical term sometimes used by researchers to describe the safe passage of “zoonotic pathogens”—diseases that are passed from animals to humans. Both Ebola and Zika are zoonotic. Not surprisingly, the flu is just such a beast.

Where do these viruses originate? And how do they get into our bodies? We learn here it is often a multi-transitional process. Similar to many bacterial infections, there is usually a reservoir host, a source organism or animal that acts like a “safe house” to the virus. Most reservoir hosts, such as bats, or rats or field mice, aren’t particularly affected by the virus itself. Which is how viral disease manages to thrive over time.

Flu’s reservoir is most often avian. In particular, wild avian. A typical flu strain is initially picked up from human interaction with domestic fowl, who, in their turn, were previously infected by wild migratory birds. The vector from wild to domestic is thought to be the bits of infected dung left behind in pond water by the wild birds, incidentally ingested by the domestic birds. Want to know where this is likely to occur? Look for massive numbers of chickens and ducks for sale in dense population centers, and there you have ground zero for the next “outbreak.”

The most common flu viruses have evolved some impressive tools needed for spillover from birds to humans, and future strains pose the greatest risk. The tools in question are microscopic proteins that protrude from the outer edge of the “viral package”—proteins known as “H” (hemagglutinin) and “N” (neuraminidase). The “H” protein helps the virus invade the next target cell. The “N” protein helps it escape and move on to another. It is the combination of proteins (there are 144 possible variations) that provide each strain’s peculiar invasive abilities.

So now you know the significance of the common flu designations, H1N1 and H3N1 and so forth. These represent various adaptations that allow some flu viruses to infect birds, others to infect humans, and some to infect both birds and humans. Not to mention horses and dogs and sheep—you name it.

But how do we survive this onslaught? Every time you get the flu, yes, you build up immunity. The same applies to the yearly flu shot, though in a lesser degree (the vaccine itself provides the “H” antigen alone). The more people who are so exposed, the higher our “herd immunity” and the lesser chance of a pandemic … but only for a particular strain.

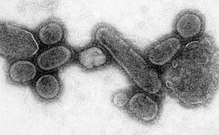

The Spanish flu virus

reconstructed in 2014.

We now know that a plague is not heaven-sent. The science has provided public health officials with a plethora of information. And in 2014, thanks to a flu-bitten body preserved in the Alaskan permafrost, scientists were able to reconstruct the Spanish flu virus. From this and other research we have learned that immunity is predicated on previous exposure to the same strain of virus.

Now here’s the rub. Some scientists think the next pandemic might be one that has already spilled over, but has not yet evolved transmissibility among humans. Such a monster is H5N1, the so-called “bird flu.” H5N1 continues to spillover every few years. When it first appeared in 1997, scientists didn’t recognize it. It initially stumped the CDC. Finally a Dutch scientist took a vial home with him.

The Dutchman informed his international colleagues that it looked like an H5. “And we all said, ‘no, impossible,’” [Robert] Webster recalled. “Since H5 doesn’t affect humans. We thought it was a mistake.” It wasn’t … this was the first case of a purely avian influenza virus—containing no human-flu genes brought in by reassortment—to cause killer respiratory illness in a person. p. 508

For those who get infected with H5 now, it comes directly from birds, either from the virus entering their bodily fluids, or from the consumption of meat. Prepare yourself. Victims have a one-in-three chance of dying.

At this time, the H5N1 strain cannot be passed along from one human to another. But that was also the case with many other viruses. Ebola, once only transmissible from bats to gorillas, over time became transmissible from gorillas to humans—and now, as we know, can jump from human to human.

Any influenza virus that “successfully adapts” and becomes transmissible through cough or sneeze, is to be feared. We can hope for the best, but we must plan for the worst.

LAURA SPINNEY “Pale Rider” (2017)

Against other things it is possible to obtain security, but when

it comes to death we human beings live in an unwalled city.

– Greek philosopher Epictetus

We are reminded every winter how vulnerable we are. At the furthest extreme, our movies and sci-fi novels—“Contagion” (2011), “Outbreak” (1995), “The Andromeda Strain” (1971)—invite us to participate in the unimaginable.

The word epidemic comes from the ancient Greeks. It referred to any major event that propagates throughout a country, from fog to rumor to civil war. Hippocrates was the first to use it in a medical sense. For centuries it was the job of priests and magicians to expel the demons of disease with standard tools of the trade: spells, potions, incantations. But Hippocrates rigorously sought a scientific basis and concluded, rightly, that “bodily humors” went out of balance due to some external influence. He concerned himself with deriving hypotheses.

As the Greeks were aware, viruses surround us, waiting for an opportunity to pounce. We might even bring them along with us. Conquistadores brought disease to the new world and exposed the un-immune Aztecs and other native Americans to all manner of fearful death.

The Spanish flu did not come from Spain, but the country-based naming convention was already well-established. In 1852 there was the Russian flu. In 1918, it depended on where you lived.

In Senegal it was the Brazilian flu and in Brazil the German flu, while the Danes thought it ‘came from the south.’ The Poles called it the Bolshevik disease, the Persians blamed the British, and the Japanese blamed their wrestlers after it broke out at a sumo tournament. – Spinney, p. 64

In some countries it was misdiagnosed as typhus, or tuberculosis. The concern from seasoned public officials was how to limit the damage.

We began to learn about prevention in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Your school, your office, your buses, subways, restaurants and movie houses are the absolute best places to receive the virus. In some countries “Sanitary Brigades” fanned out to ensure water quality, control pests, and ensure clean living conditions. The flu flourished anyway.

We began to learn about prevention in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Your school, your office, your buses, subways, restaurants and movie houses are the absolute best places to receive the virus. In some countries “Sanitary Brigades” fanned out to ensure water quality, control pests, and ensure clean living conditions. The flu flourished anyway.

The best advice at the time? Wear masks and stay away from most other people. Well, it couldn’t hurt.

It is odd that while many people in a pandemic get infected, some don’t. In 1957 and 1968, the most at-risk generations were those who had not been previously exposed to the specific strain of the latest flu. Some researchers now believe the depth and viciousness of the 1918 flu among people in middle-age was caused by a lack of immunity to that strain.

Albert Gitchell, a mess hall cook at Camp Funston in Kansas, was the first-known case. On March 4, 1918, Gitchell reported to the infirmary with a sore throat, fever, and headache. Within hours there were more than a hundred cases reporting. Within a few short weeks, the chief medical officer had to accommodate the sick in an airplane hangar. It is theorized that an avian or porcine vector was at fault, as the Great Plains was becoming the agriculture center of our American civilization.

Albert Gitchell, a mess hall cook at Camp Funston in Kansas, was the first-known case. On March 4, 1918, Gitchell reported to the infirmary with a sore throat, fever, and headache. Within hours there were more than a hundred cases reporting. Within a few short weeks, the chief medical officer had to accommodate the sick in an airplane hangar. It is theorized that an avian or porcine vector was at fault, as the Great Plains was becoming the agriculture center of our American civilization.

This was only the first wave. With troops on the move in America, and mass migrations overland and via trains and ocean-going ships, the disease easily spread about the world. Overseas the first cases cropped up in North Africa, then in China. Soon afterward Germany, Poland, Russia, Japan, and Australia were infected. It disappeared in the early summer.

In August came the second wave: Sierra Leone, Boston, Switzerland, and Brest, France led the way. Quarantines were starting to be enforced at borders. The flu, like a cagey illegal immigrant, kept charging through.

The flu is known among researchers as a “crowd disease.” Historians and scientists have identified several major flu epidemics since the middle ages in which the flu devastated armies. With the advent of germ theory in the late 19th century, vaccination programs (as controversial then as now) had in some cases helped stem the tide.

Eventually a third wave arrived, the most virulent. After just a few days there were no more coffins available. Families were instructed to leave their dead on the doorways so that trucks and carriages could canvas the streets, and pick up the corpses. In many urban areas officials had been loath to close public spaces, and there the carnage was particularly intense—11,000 in Philadelphia alone. Mass graves had to be dug. In the month of October the official count exceeded 195,000 in the U.S.

Hundreds of deaths occurred aboard transit lines. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt took sick on the SS Leviathan. All African ports, and ports of call along the coasts of India, Persia, China and Great Britain were stricken, as were military transports and supply routes along the Trans-Siberian rail. Real suffering occurred on board ships and trains between ports, as if the intensity was strengthened by the closeness of the inhabitants. In the cities, in the trenches, in hospitals and gymnasiums and aircraft hangars turned into wards—the people were simply too close. In Rio de Janeiro, the veneer of civilization collapsed in the face of food shortages and “thieving mobs.”

While normal flu affected only upper respiratory organs, the Spanish flu had a tendency to commandeer the lower extremities as well. You could spot a dying victim by the color of his skin:

Slight changes in tint were informative about the patient’s prognosis. It was ‘an intense dusky, reddish plum’ … but as long as red was the dominant hue, there was room for optimism. Blue darkened to black. The black first appeared at the extremities—the hands and feet, including the nails—stole up the limbs and eventually infested the abdomen and torso. As long as you were conscious you watched death enter at your fingernails and fill you up. -Spinney p. 46-47

People said the Spanish flu had a smell, as of musty straw. “I never smelt anything like it,” recalled one nurse. Teeth fell out. Hair fell out. Delirium was common. Many deaths, they say, occurred not from flu but the rush of pneumonia.

As the flu subsided, one newspaper triumphantly cried out: “Only 63 Deaths Yesterday.” People felt heartened, but Armistice parades were held with masks. Billy Sunday took some credit—he had held a three-month long revival meeting in Washington, D.C., to “pray down the flu” just like he had done with the “German threat.” Camphor balls, mints, turpentine, and all manner of quackery were consumed in abundance, and for years afterward some patients credited these elixirs for their miraculous recovery.

KATHERINE ANNE PORTER

“PALE HORSE, PALE RIDER” (1939)

Of the many new and engaging writers who emerged in the ’teens and 20’s, nearly all experienced the horror. But only one, the southern-born writer Katherine Anne Porter, who nearly died from it, devoted an entire novella to exploring the tragedy and gripping terror of the event.

Porter despised the word novella. It was, she thought, a term of belittlement. Her preference was for “short novel” or “the long story”—a form that was perfectly suited to her gift for nuance and southern ambiance—and that gave a pulse to those salt-of-the-earth Louisiana folks struggling to cope, living lives that tend at any moment to reel out of control.

This collection, published twenty years after the pandemic, is comprised of intersecting stories. The first two (“Old Mortality” and “Noon Wine”) are vintage Porter: vividly Gothic, deeply southern, graced with dark humor, pitted with poverty, whiskey, cruelty, early death. Stories, in other words, that are both faithful to the era and deliciously scandalous.

But it is the first and third stories that are linked by the early life and later young adulthood of one Miranda, who is the heart and soul of an earlier version of Porter herself—a bit like Hemingway’s Nick Adams. The mysterious goings-on in “Old Mortality” are seen largely through the eyes of this young, hapless Miranda, a wide-eyed lass earnestly desirous of a more thrilling life. The unending object of her curiosity was her once-vivacious Aunt Amy who died at a young age from what appears to have been the effects of a bad marriage. On the mantle, Aunt Amy’s picture haunted her:

There was a kind of faded merriment in the background, with its vase of flowers and draped velvet curtains, the kind of vase and the kind of curtains no one would have anymore. The whole affair was associated, in the minds of the little girls, with dead things: the smell of grandmother’s medicated cigarettes and her furniture that smelled of beeswax and her old-fashioned perfume, Orange Flower. p. 4

It is the 1890’s. Miranda endures a long winter at a convent school, spends a day at the race track, meets the uncle with a “drinking problem,” and the uncle’s new wife Honey who is stricken with depression. In the end Miranda encounters a grownup cousin Eva who, in the course of a carriage ride, reveals the decade-old mystery behind Aunt Amy’s sudden departure.

But it is the final story, “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” that breaks new ground. We are transported to the new century with a frightfully grown up Miranda, in a world without answers to any mysteries. It was an era of castaways.

Miranda arrives—and we return—to that fateful year, 1918. She is ensconced in Denver, having relocated “out west” like so many other Americans to take advantage of the ever-present sun and bone-dry air. She is somewhat restless and freewheeling, curious but sarcastically inclined, and a bit of a pessimist, having been “funneled” along with her girlfriend Towney into one of the two routine female jobs at the local newspaper.

Which is to say Miranda was the theater critic and Towney the society page editor. The resentment stings. But also gradually dawning on Miranda, now about 30, is that sense of old mortality, a sense accompanied by physical unease. She felt occasionally disoriented—perhaps a bad cold?—as well as discouraged. Three years is too long to be hanging around the grizzled old newspaper editors waiting for an exciting life to materialize. Why had she not left?

Miranda is diminished, disillusioned, stuck in a drab existence, derelict in her patriotism, scornful of war. And the charities!—all that “wallowing in good works.” She volunteers out of obligation. In her frumpy Red Cross “head dress” she delivers flowers to the recovering soldiers. She refuses to shell out for even one of those Liberty Bonds—it isn’t so much she can’t afford the five dollars a week, but she has her principles. She despises politicians. She loathes the war. She abhors the nonstop anti-German propaganda. She refuses to buy in.

Yet day after day there was this nagging uneasiness, and those bizarre headaches. A kind of prickliness overcomes her: “even her hair felt as if it had decided to grow in the other direction.”

But there’s this guy, Adam, who throws a wrench of fateful passion into her mess of a life. Ironically, if it weren’t for the soldiers at the base and the hospitals—soldiers recovering from both wounds and flu—she would never have found Adam.

Miranda is a character so quirky and true-to-life you are immediately drawn into her tentative and uncertain romance with this young soldier on leave for a few short weeks. He is being shipped out to the front for the first time. He is “infinitely buttoned, strapped, harnessed into a uniform as tough and unyielding as a strait jacket”—but oh so romantically anonymous. They have only a few days. He looks every bit as delicious to her as “a fine healthy apple” … “his eyes pale, his hair the color of a haystack” (p. 157). They go dancing late at night, after her obligatory review outings at the theater.

Still she finds herself growing feverish and smitten at the same time, so often falling into a woozy swoon. She aches for Adam but her body aches as well … flu symptoms? Flu was popping up everywhere. For the first time in ages people are dying on the streets, dropping like flies on the glorious “home front.” Miranda banishes the thought. She chooses to ignore the fleeting suspicion—in fact, she purposely pays no attention. She could hold on to one thought only, the thought of Adam, of being with him every free minute of whatever life was left them.

Such floundering was widespread. Do you have it, or don’t you? There was really nothing anyone could do. You get the bug, you endure. You hold on. Her fellow journalists were riveted by any and all news of the disease. Even Towney falls into a swoon of her own—infatuation with the current conspiracy theories.

“They say it is really caused by germs brought by a German ship to Boston … maybe it was a submarine … somebody reported seeing a strange, thick, greasy-looking cloud float up out of Boston Harbor and spread slowly all over …” p. 162

Towney gradually goes batty. Miranda begins bumping into reality. On her outings with Adam, the two lovers regularly have to stop and stand in honor … of the dead. What a reality check. On the streets, ambulances pass. Trucks are given right-of-way on their rendezvous with death. The hearses are so much more in evidence. The daily counts soar.

Miranda wants to flee the unreality of this reality. Flee because these two impossible lovers cannot get enough of each other, talking, picking over snacks and coffee at the greasy spoons. They go out dancing late into the night, hiking in the mountains, always leaning into each other and laughing and drinking in all the sights and the great views.

She knows in her marrow that something is coming on. “I can’t smell or see or hear today,” she tells Adam. “I must have a fearful cold.” On an outing to one of their midnight dance hall haunts, Miranda and Adam have to stop and wait again. A funeral procession passes.

Yet she is becoming unmoored. More and more these moments slide this way and that. The next night, reeling from too little sleep and too much dancing and way too much beer and cigarettes, the pains in her chest and her heart are getting too much to bear. She worries about her lover going off to war. She beseeches him.

“I am in pain all over and you are in such danger as I can’t bear to think about, and why can we not save each other?” p. 178

Then, within what seemed only moments … as if no time had passed … Miranda wakes up.

She is in bed … Adam is standing at the door … she senses that she had not gone in to work … a doctor had apparently been dispatched by the office … a prescription left on the table. The flu? Her landlady Miss Hobbe is horrified. Miranda slips in and out of consciousness … dreaming … with glimpses of Miss Hobbe and Adam and Bill, her editor, going in and out of her room …

Adam tries to find a hospital but beds are not to be had in the city. Miranda is forced to drink orange juice and eat ice cream—two of the “antidotes” routinely recommended to flu patients. Over and over Miranda falls into feverish delirium. The newspaper office finds her a place in a sanatorium. She hardly wakes. She dreams of jungles and of ships sailing away in the dark:

A secret place … creeping with tangles of spotted serpents, rainbow-colored birds with malign eyes … screaming long-armed monkeys tumbling among broad fleshy leaves that flowed with sulphur-colored light and exuded the ichor of death, rotting trunks of unfamiliar trees sprawled in crawling slime. -p.183

When she does wake, she tells Adam about a song she recalls from her Louisiana youth.

Pale horse, pale rider

done taken my lover away …

They are the words, she says, sung by sharecroppers … long ago … in the fields. But she slips back into seeing feverish apparitions, again and again, ever more often. She has visions of flight and falling, delusions and dreams of approaching death.

The two living men lifted a mattress standing hunched against the wall, spread it tenderly and exactly over the dead man. Wordless and white they vanished down the corridor, pushing the wheeled bed before them. … A pallid white fog rose in their wake insinuatingly and floated before Miranda’s eyes, a fog in which was concealed all terror and all weariness, all the wrung faces and twisted backs and broken feet of abused, outraged living things, all the shapes of their confused pain and their estranged hearts; the fog might part at any moment and loose the horde of human torments. p. 196

Visions repeat upon themselves, she feels the movement of her life rushing toward an end-life.

Death is death, and for the dead it has no attributes. Silenced she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body, entirely withdrawn from all human concerns, yet alive with a peculiar lucidity and coherence … and there remained of her only a minute fiercely burning particle of being … itself composed entirely of one single motive, the stubborn will to live. p. 199

Katherine Anne Porter

Porter herself was deathly ill with the Spanish flu. She suffered the effects for many months, and her physical, mental and spiritual recovery lasted many more.

During her bout, she lost all her hair. When her hair finally grew back, it was white, all of it, and remained so the rest of her life. We are fortunate she lived to make literature out of an event that was rarely discussed.

It is an amazing, almost surreal book. Once Miranda recovers from the flu, after weeks and weeks go by, she learns that her Adam has succumbed. While that is not quite the end of the story, it is poignantly delivered in the matter-of-fact punch of Porter’s style, injecting this great “long story” with a tragic denouement.

She was asked about Adam in 1956.

“It’s in the story.” At the sudden memory she fought back tears—and won gallantly. “He died. The last I remember seeing him . . . It’s a true story . . . It seems to me true that I died then, I died once, and I have never feared death since . . .”

– reported by Charles Mercer, Denver Post, March 22, 1956

A Brief Gloss

on Pandemic, War, and Apocalypse

In those days most readers would have recognized the figures in Porter’s title—the pale horse and its rider—as these two creatures were made manifest in the “Book of Revelation.” There, they ride forth as the last of the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.”

From ancient times to the present day, at each new eruption of the catastrophic, people still ask: have we at long last arrived at the final chapter of our life on earth? Is this now the prophesied end?

In the Bible, this fourth horseman ushers in a terrifying era of the world’s last days. The horse is indeed “pale” and eerily lifeless, a symbol of decay. Its rider—darkness or Death—is usually taken to be the Devil himself. Sickness, devastation, natural disasters and pestilence simultaneously ensue—coming together in one great tsunami of misery. All God’s creatures are helpless to prevent it.

Such grand biblical symbolism was not out of the ordinary in twentieth century art. I am reminded of Ingmar Bergman who broke into the mainstream with “The Seventh Seal” (1957), also a nod to the apocalypse. That movie’s title refers to the final “seal” of biblical prophecy from the Book of Revelation. It is a span of end-time when heaven goes silent, and God turns away from the suffering on earth.

In this dark, cold, brutal world, Bergman conjures a medieval knight, fresh from the Crusades, returning to Sweden in the midst of the Black Death. In the course of his journey he settles in for a game of chess with a sullen and deathly pale monk who has arrived to reap his harvest.

In this dark, cold, brutal world, Bergman conjures a medieval knight, fresh from the Crusades, returning to Sweden in the midst of the Black Death. In the course of his journey he settles in for a game of chess with a sullen and deathly pale monk who has arrived to reap his harvest.

It is the end game. The monk is confident he can retrieve his clutch of victims. The knight is in it for a chance to live. Both are sorely tested.

Leave a Reply