An All-New Moby-Dick

A Lookingglass Night at Alliance Theatre

In October of 2016, Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre hosted a new adaptation of “Moby-Dick” that wowed the crowd. The play was forged in Chicago, at the home of a regional powerhouse called Lookingglass Theatre. Stunning in its presentation, wildly sensational in its special effects, it certainly had a number of critics chattering.

In October of 2016, Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre hosted a new adaptation of “Moby-Dick” that wowed the crowd. The play was forged in Chicago, at the home of a regional powerhouse called Lookingglass Theatre. Stunning in its presentation, wildly sensational in its special effects, it certainly had a number of critics chattering.

Having myself feasted on the book “Moby-Dick” over 30 years ago, I bounded out of the Alliance Theatre that night with a mind to take a step back to the original, and read it yet again. I wanted to know more about what moved me in the performance, to explore what makes a great story continue to impress. I wanted to check out the movie adaptations, all of them. And in the end, I wanted to leap beyond the bounds of that movie realism, and back into the ethereal air of this new kind of symbolic spectacle.

But how meaningful is all this hubbub? Why should it be earth-shaking that in one little theater our dusty old Herman Melville was successfully transformed to sparkling relevance?

It is good to ask the obvious. Is the foundational work itself still a living and breathing thing? How does this latest adaptation compare to the original, or to other adaptations? Will it surpass the motion picture efforts of recent years? Can the theater itself be a new starting point for this classic, this heart-stopping descent into one man’s madness, with a backward glance to the tragic vision of old?

Lots of questions, not many answers. Not yet.

A Plethora of Adaptations

A somewhat dated but useful article in Wikipedia (Adaptations of Moby-Dick) lists numerous “Moby-Dicks” in the form of plays, operas, musicals, graphic novels, ebooks and, of course, motion pictures—all, in a sense, adaptations, lifelines to the great work. And it may very well be that adaptations are the reason we remember classics like “Moby-Dick” at all—we exalt them not because we read the book or the abridged version or the Cliff Notes—but rather because we’ve all seen the movie versions or otherwise heard of them. In the days of my youth, movies with epic stories like “The Grapes of Wrath” and “The Old Man and the Sea” recalled a lost culture, and were as much a part of our heritage as juke boxes and Model T’s.

Nowadays each generation hearkens back to its great writers and artists for inspiration, and carves out any number of new ways to present classic works to a modern audience. But know this: back when it all started, book authors complained bitterly. They thought of adaptations as something nefarious—soul-stealing doppelgangers, unfaithful, overly sentimental, mere imitations—bowdlerized was the word they used. But then came movie options and franchises and spin-offs and tie-ins and sequels. Today we are scarfing down more adaptations than ever.

The accepted wisdom is that classics such as “Moby-Dick” no longer make for the best commercial adaptations. The golden days of popcorn and a “Jane Austen movie” seem quaint next to the onslaught of the clever and sassy originals and un-originals we are subjected to now. Out of this adaptation frenzy, a new field of study has arisen: Adaptation Theory, which aims to explore the creative and commercial process of every manner of artistic restyling.

A plethora of popular adaptations, like those of Sherlock Holmes, now live in the ever-growing space of television and motion pictures. But why restrict our options? We also happen to live in a brand new era of the arts, daring and innovative and stylistically imaginative. To survive, theater and opera and modern dance have no choice but to transcend the relentless emphasis on visual realism which applies even to special effects created for, and judged by, the realist model.

Herman Melville “MOBY-DICK, OR THE WHALE” (1851)

To begin, why that name Moby-Dick? Turns out, it was a writerly knock-off, originated from the handle of a well-known whale of the 1830’s in a widely disseminated account in newspapers and magazines of the day:

Mocha Dick: or The White Whale of the Pacific recounted the capture of a giant white sperm whale that had become infamous among whalers for its violent attacks on ships and their crews. The meaning of the name itself is quite simple: the whale was often sighted in the vicinity of the island of Mocha, and "Dick" was merely a generic name like "Jack" or "Tom". – Melville.org

Mentioned, in Chapter 45 of Melville’s novel, are the whales Timor Jack and New Zealand Tom. You might say that for every Tom, Dick, and Jack there was a notorious whale to go with the name. To the reading public, Mocha Dick himself loomed larger than life: a sort of Bigfoot of the early 19th century. Melville took this legend and married it to another phenomenally well-known incident, the sinking of the Essex in 1820, purportedly by a whale of similar instinct.

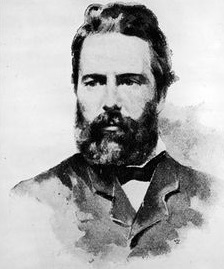

Herman Melville c. 1840

The book “Moby-Dick,” often presumed to be on the all-time Greatest Hits of American Literature, was not so popular in its day. Melville’s early writing career was somewhat meteoric. His first book was a big bang—“Typee” (1845)—and several books thereafter also did rather nicely. But over an amazingly short outburst of creativity, from the 1840s to the early 1850s, his book sales actually declined. He nevertheless stuck steadfastly to sea adventure, his first passion. He exercised no restraint in the pursuit of artistic excellence, publishing three sailing books in the space of three years—“Redburn” (1849), “White Jacket” (1850), and “Moby-Dick” (1851).

As such, Melville’s fortunes at the roulette wheel of popular taste diminished rather than multiplied. It may not have helped that the novel was 600 pages plus. Nathaniel Hawthorne argued it was fine book, a noble book, but critics were unmoved. Still, reviews alone are not killer harpoons. It may have been that the fickle reading public had simply lost interest. Serials were fast becoming all the rage.

It was actually the “Melville Revival” of the 1920’s that catapulted “Moby-Dick” into the literary sensation that we think of it today. We have 20th-century readers and scholars, and even the general public, to thank for Melville’s earthly resurrection. Melville, himself an author thoroughly immersed in Biblical references, would have relished the irony.

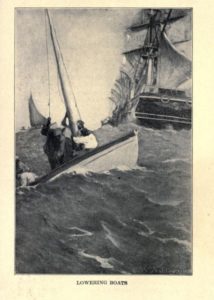

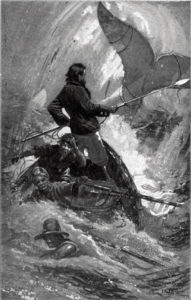

Whaling SCENES OF THE ERA

In one of his more notable novelistic innovations, Melville steps in for his narrator now and then, speaking directly to his readers. The topics range widely. As he pauses to elucidate, he might for example offer up a topic or two of clarification: here a natural history of whales, there a disquisition or two on types of whales, and so forth.

One such topic is on pictorial whaling scenes, and in typical fashion Melville is anxious to correct common misconceptions. In Chapter 55 (“Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales”) Melville takes on misleading representations, and in Chapter 56 (“Of the Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales, and the True Pictures of Whaling Scenes”) he makes note of two of his favorites, which he had seen at museum at Versailles, both of them raucous and visual depictions the masterful work of French illustrator Ambroise Louis Garneray (1783-1857).

In our era we need not voyage to France to see them. The pictures are meant to be what we might call photorealist. Melville, himself a one-time whaler and now eager to share his stamp of approval, testifies enthusiastically not only for their realism but their “living and breathing commotion on canvas.”

In the first engraving a noble Sperm Whale is depicted in full majesty of might, just risen beneath the boat from the profundities of the ocean, and bearing high in the air upon his back the terrific wreck of the stoven planks. The prow of the boat is partially unbroken, and is drawn just balancing upon the monster's spine; and standing in that prow, for that one single incomputable flash of time, you behold an oarsman, half shrouded by the incensed boiling spout of the whale, and in the act of leaping, as if from a precipice. – “Moby-Dick” Chap. 56

Ambroise Louis Garneray, “Peche du Cachalot,” colored aquatint engraved by Frederic Martens, 1834

In the second engraving, the boat is in the act of drawing alongside the barnacled flank of a large running Right Whale, that rolls his black weedy bulk in the sea like some mossy rock-slide from the Patagonian cliffs. His jets are erect, full, and black like soot; so that from so abounding a smoke in the chimney, you would think there must be a brave supper cooking in the great bowels below. – “Moby-Dick” Chap. 56

Ambroise Louis Garneray, “Peche de la Baleine,” colored aquatint engraved by Frederic Martens, 1835

The Achievement

“Moby-Dick” now ranks among the greatest stories ever told that almost no one has ever read. In a few short years Melville had been driven to ever greater heights by a new vision of the possible. In so doing, he had made it to a very solitary mountaintop.

Lowering the Boats

What set this book apart was its synthesis of formal style and exotic storytelling, as well as a new conception of the novel itself. As steeped in the Bible as any writer of his day, by the time he was writing “Moby-Dick” Herman Melville was also devouring Shakespeare’s plays and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essays. He had recently made friends with one Nathaniel Hawthorne who lived close by. And he had begun to feel himself a part of the new romantic sensibility of American writers—a groundswell of literary output that would, a century later, be dubbed the American Renaissance.

In the book “Why Read Moby-Dick?” Nathaniel Philbrick says Melville wrote in a “mesmeric state”—a fact that could not have been lost on his few readers. Melville took aim at the highest achievement imaginable: the epic. He created a new kind of novel, indelible characters, and a mystical-mythical story (based on a well-known event) that somehow still lives and breathes today.

Ishmael

Ishmael is narrator and witness—naïve and gullible, but cast of a hearty mettle. Ishmael is our eyes and ears to the unfolding of the story. Ishmael is sailor—but still green-horned enough to be wide-eyed and wowed by a new adventure at sea. Ishmael is spirit—“I am tormented by an everlasting itch for things remote” (Chap. 1). We believe in this story because Ishmael delivers it with unabashed excitement, and in believable and finely drawn detail.

The Pulpit, The Sermon, and Father Mapple

Though staying at New Bedford’s Spouter Inn for but a fortnight, Ishmael discovers Sunday is for church-goers. Father Mapple climbs a rope ladder to the “deck” of the pulpit, pulls the ladder up to his feet, turns to the congregation, stands with both hands astride the great leather-bound Bible behind the “paneled front in the likeness of a ship’s bluff bows”, and delivers his great monolog, a sermon on Jonah. (Chaps 8-9).

Queequeg

Strapping Peloponnesian harpooneer, sculpted and muscular, bald but for a top knot, sometimes called a “cannibal” or “a pagan” whose “heathenish ways” include tattoos galore, a tomahawk pipe, and a tiny black figurine named “Yojo”. He is Ishmael’s friend, mostly quiet and self-contained, utterly accurate in his harpoon aim, his father a king of Kokovoko, his uncle a high priest. Queequeg admits he had once wanted to become Christian but was disabused of that idea after having seen his fellow whalers as “wicked as all his father’s heathens.” (Chap. 12). All the harpooneers on the Pequod, by the way, were non-Europeans: Queequeg (from the South Seas), Tashtego (an American Indian), Daggoo (an African sailor who calls Nantucket home), and Fedallah (a “Parsi” from China) dedicated to Ahab’s personal boat. One of the great joys of Melville is his unfettered egalitarianism.

Starbuck, Stubb, and Flask

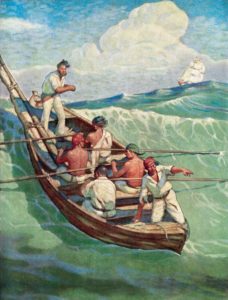

Starbuck and crew

First, second, and third mates aboard the Pequod, each his own man, Starbuck the anguished Quaker and pragmatist, alone in opposing Ahab; Stubb the high-flying lowbrow whose zest for whale hunting and much-enjoyed patois is a favorite subject of Ishmael’s; Flask the loyal kniver and opportunist. Starbuck stands alone in confronting Ahab: “I came here to hunt whales, not my commander’s vengeance …. vengeance on a dumb brute that simply smote thee from blindest instinct! Madness! To be enraged with a dumb thing, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous.”

Ahab

The menacing Captain of the Pequod, who hobbles about on his ivory leg (“fashioned from the polished bone of a sperm whale’s jaw” – Chap. 28) and upon his visage wears a lightning bolt scar with the aspect of a crucifix—and has but one goal, to wreak vengeance upon the storied white sperm whale who on a previous voyage robbed him of his leg and rightful honor. Revealed later are his own private boat crew, including four Chinese stowaways (Chap. 43), one of whom is Fedallah. Ahab retorts to Starbuck: “It was Moby-Dick that dismasted me; Moby-Dick that brought me to this dead stump I stand on …. He tasks me, he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. … I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

The Whale

Moby-Dick was a sperm whale, and an albino, and … found ’round the globe? At regular intervals such was rumored amongst the many whaling shipmates the world over. To the whaler, a whale was but a kind of fish—even so, there is a power and prestige to the animal; there is a universality. Whalers ranked themselves by the type of whale and deathly differences between Right Whale hunters and Sperm Whale hunters were in very different categories, politely put. But the whales themselves? All God’s creations … except maybe a few.

The First Lowering

Although we are focused on adaptations, no better place than here for a taste of that man vs. nature thing and a sample of Melville’s grandeur.

Let us take but a few sentences from Chapter 48, “The First Lowering”. Here is Stubb, calling out to his boat crew as they dip their oars into the lapping waves and head out for battle.

“Three cheers, men—all hearts alive! Easy, easy; don’t be in a hurry. Why don’t you snap your oars, you rascals? Bite something, you dogs! So then softly, softly. That’s it, long and strong. Give way there! The devil fetch ye ragamuffin rapscallions; ye are all asleep. Pull, will ye? Why in the name of gudgeons and ginger-cakes don’t ye pull?”

Comes a squall. Suddenly from the dark sky, a rousing sea rears up as the boats approach their whale closest by.

The vast swells of the omnipotent sea; the surging, hollow roar they made, as they rolled along the eight gunwales like gigantic bowls in a boundless bowling-green; the brief, suspended agony of the boat, as it would tip for an instant on the knife-like edge of the sharper waves, that almost seemed threatening to cut it in two; the sudden profound dip into the watery glens and hollows; the keen spurrings and goading to gain the top of the opposite hill; the headlong, sled-like slide down its other side—all these with the cries of the headsman and harpooneers, and the shuddering gasps of the oarsmen, with the wondrous sight of the ivory Pequod bearing down up on her boats with outstretched sails, like a wild hen after her screaming brood.

Then—nearly a disaster, narrowly averted.

A short rushing sound leaped out of the boat; it was the darted iron of Queequeg. Then all in one welded commotion came an invisible push from astern, while forward the boat seemed striking on a ledge; the sail collapsed and exploded; a gush of scaling vapor shot up nearby; something rolled and tumbled like an earthquake beneath us. The whole crew were half suffocated as they were tossed helter-skelter into the white curdling cream of the squall. Squall, whale, and harpoon had all blended together; and the whale, merely grazed by the iron, escaped.

The Destination

The Pequod’s destination, alas also its destiny, is set by Ahab from the beginning. Around Cape Horn it must sail, and across the Indian Ocean to the islands of the South Seas. This is “equator country,” the waters where Moby-Dick is known to thrive. On this journey there are many things for Ishmael to remark upon, not least of which are signs of the gradual coming-apart of the crew.

Ahab confronts his nemesis

Granted, the book is greater than its lone antihero, but for purposes of adaptation there is no one quite like Ahab in the American canon. He is a unique American creation. He’s not royalty, not privileged, not wealthy. He is a captain, true, but of the Pequod, a creaking old whaling ship with weathered sails and rotting decks and leaking casks of oil.

Ahab has a fearsome reputation but is not himself a man of the upper echelons, or even of the merchant class. He is a tragic figure that does not fit the tragic mold: he has not fallen from grace; he has made no pact with the Devil.

Simply put, Ahab and the gradual coming apart of the crew makes great drama. There is in him a deeply human cry of righteous indignation, of blind vengeance not only against nature, but caused by powers of nature that cannot be tamed and will not be conquered. He focuses all his mind and raging soul to devising an ingenious plan, which—against all odds, even against all devious reason—actually begins to take shape. As Ahab forcefully brings the fight to his nemesis, Melville imparts both fatalism and destiny as the crew is slowly at odds and going mad too. Having set sail, there’s no stopping the Pequod. Ahab and the whale are fated to meet again.

Ahab’s grandiose impiety may not be in the normal sense “sympathetic,” but it is our human touchstone to that warped vision we feel in the depths of our souls. His first mate, Mr. Starbuck, is the Greek Chorus we hear beckoning, piously pleading. Sure, we empathize with Starbuck’s agony as well, but it is Ahab who ultimately captures our fascination, and keeps this wonderful book aloft on the sea of famous stories.

MOVIE ADAPTATIONS (1930 – 2014)

It is doubtful that Melville—goose quill in hand, inkwell at the ready—would have considered any of this “adaptation stuff” of much importance. Melville went far beyond the facts of the case. But as indicated above, what keeps us coming back for more is the story, the characters, the dissolution of the crew under the autocratic and demented captain, the inability of loyal mates to mutiny when they had the chance, and the inevitable terror and chaos that result. Throw in a seagoing adventure and a big whale, and you have yourself a movie.

Lloyd Bacon “Moby Dick” (1930) – Motion Picture

Basically a corny remake of the 1926 silent film—the first adaptation of the book— both of which starred John Barrymore in the role of Ahab and Joan Bennett as his … uh, love interest? Well yes, the movie takes a stab at backstory. And because the tale is told objectively in the way movies used to be conceived, there is no need for Ishmael. Oddly Queequeg, depicted here as Ahab’s right-hand man, is every inch a white man “done-up” to look black. Also Ahab eventually kills Moby-Dick, and returns to his fiancée just in time for a happy ending. And yet two things stand out: (1) a maleficent and horrifying scene in which Ahab’s mutilated, severed limb is seared shut by the blacksmith; and (2) the introduction of women into the story—a theme that future generations will also reprise.

Basically a corny remake of the 1926 silent film—the first adaptation of the book— both of which starred John Barrymore in the role of Ahab and Joan Bennett as his … uh, love interest? Well yes, the movie takes a stab at backstory. And because the tale is told objectively in the way movies used to be conceived, there is no need for Ishmael. Oddly Queequeg, depicted here as Ahab’s right-hand man, is every inch a white man “done-up” to look black. Also Ahab eventually kills Moby-Dick, and returns to his fiancée just in time for a happy ending. And yet two things stand out: (1) a maleficent and horrifying scene in which Ahab’s mutilated, severed limb is seared shut by the blacksmith; and (2) the introduction of women into the story—a theme that future generations will also reprise.

John Huston “Moby Dick” (1956) – Motion Picture

Huston and writer Ray Bradbury’s valiant attempt to get it right—to faithfully and accurately depict all the major scenes of the novel. Ishmael and Queequeg and life aboard ship don’t disappoint. Gregory Peck is dark and foreboding as Ahab, but always said later that he came up short in the portrayal—needing what a New York Times reviewer called “a little more tempest, a little more Joshua in the role.” The whale himself is a stagey artifact of a movie era not yet technically adept. But still, in this movie, Moby-Dick is one of those creatures we want to believe in. A lot of real-life whaling footage from the English seas is effectively cut into the scenes … and Orson Welles as Father Mapple, the whaler’s preacher, cannot be topped.

Huston and writer Ray Bradbury’s valiant attempt to get it right—to faithfully and accurately depict all the major scenes of the novel. Ishmael and Queequeg and life aboard ship don’t disappoint. Gregory Peck is dark and foreboding as Ahab, but always said later that he came up short in the portrayal—needing what a New York Times reviewer called “a little more tempest, a little more Joshua in the role.” The whale himself is a stagey artifact of a movie era not yet technically adept. But still, in this movie, Moby-Dick is one of those creatures we want to believe in. A lot of real-life whaling footage from the English seas is effectively cut into the scenes … and Orson Welles as Father Mapple, the whaler’s preacher, cannot be topped.

John Aranson “Moby Dick” (1978) – One-Man Play (Video taping)

If you’re partial to both Melville and one-man plays, this performance is definitely worth a look—if nothing else just to see the Shakespearean John Aranson tackle all the major characters, like them or not, each with his own facial expressions, each his own stance and pitch of walk, each his own accent. Just for kicks Aranson throws around a Scottish brogue here, and an Irish or English dialect there, to say nothing of his halting Queequeqese. Not a showing that you’d want to experience without actually having read the book, however.

If you’re partial to both Melville and one-man plays, this performance is definitely worth a look—if nothing else just to see the Shakespearean John Aranson tackle all the major characters, like them or not, each with his own facial expressions, each his own stance and pitch of walk, each his own accent. Just for kicks Aranson throws around a Scottish brogue here, and an Irish or English dialect there, to say nothing of his halting Queequeqese. Not a showing that you’d want to experience without actually having read the book, however.

Franc Roddam “Moby Dick” (1998) – Movie Made for TV

Dramatically, this may be the best of the Ahab film adaptations. Patrick Stewart, as expected, plays as deranged a whaling captain as the big screen will allow, and Ted Levine supplies his opposite, the morally-disgusted, spiritually agonized Starbuck, with a sympathetic and believable depth of despair. But an oversized Stubb, XX-Large? A Queequeg who roars with backslapping laughter? And a majestic whale three times the size of any real animal since the precambrian? I jest you not. I guess, as with most adaptations, you must expect a regular squall of exaggeration from scene to scene—but must the stereotypical always come with the territory?

Dramatically, this may be the best of the Ahab film adaptations. Patrick Stewart, as expected, plays as deranged a whaling captain as the big screen will allow, and Ted Levine supplies his opposite, the morally-disgusted, spiritually agonized Starbuck, with a sympathetic and believable depth of despair. But an oversized Stubb, XX-Large? A Queequeg who roars with backslapping laughter? And a majestic whale three times the size of any real animal since the precambrian? I jest you not. I guess, as with most adaptations, you must expect a regular squall of exaggeration from scene to scene—but must the stereotypical always come with the territory?

“Moby Dick” (2011)— Movie Made for TV (Drama)

Scenically, this is by far the best realistic movie, but dramatically an odd turn as modernist actors Ethan Hawke (Starbuck), Donald Sutherland (Father Mapple), and William Hurt (the method actor’s Ahab) attempt to bring a fresh new interpretation and irony to the classic tale. I kind of got used to Hawke’s dispirited Starbuck, but Hurt’s underplayed performance is a bit of a swallow. For me that aligns with way too many rewritten scenes revised for modern sensibility (example: cabin-boy Pip’s backstory is as a beaten Negro servant rescued by Ishmael on the way to Nantucket). And yet British actor Eddie Marsan does Stubb to perfection, well worth the price of admission. This movie also has the best cinematography bar none, and the most realistic whaling ship and seafaring scenes you’ll ever see, especially the skinning and cutting and boiling of the blubber. Sometimes boring isn’t bad.

Scenically, this is by far the best realistic movie, but dramatically an odd turn as modernist actors Ethan Hawke (Starbuck), Donald Sutherland (Father Mapple), and William Hurt (the method actor’s Ahab) attempt to bring a fresh new interpretation and irony to the classic tale. I kind of got used to Hawke’s dispirited Starbuck, but Hurt’s underplayed performance is a bit of a swallow. For me that aligns with way too many rewritten scenes revised for modern sensibility (example: cabin-boy Pip’s backstory is as a beaten Negro servant rescued by Ishmael on the way to Nantucket). And yet British actor Eddie Marsan does Stubb to perfection, well worth the price of admission. This movie also has the best cinematography bar none, and the most realistic whaling ship and seafaring scenes you’ll ever see, especially the skinning and cutting and boiling of the blubber. Sometimes boring isn’t bad.

Ron Howard “In the Heart of the Sea” (2015) — Motion Picture

This is the tale of The Essex, the true story behind “Moby-Dick.” With all good intentions, but a cast more suited for old cowboy movies, Ron Howard leans into the narrative with purpose, humanity and a tragic sense. Add to that a pretty cool whaling ship. But the story is not well served by depicting a whale that is way too big to believe, and constitutes the mark of all the truly lesser movies and stories and illustrations which undercut a needful empathy. “Moby-Dick” would never scale to the tragic if the whale himself was a monster.

This is the tale of The Essex, the true story behind “Moby-Dick.” With all good intentions, but a cast more suited for old cowboy movies, Ron Howard leans into the narrative with purpose, humanity and a tragic sense. Add to that a pretty cool whaling ship. But the story is not well served by depicting a whale that is way too big to believe, and constitutes the mark of all the truly lesser movies and stories and illustrations which undercut a needful empathy. “Moby-Dick” would never scale to the tragic if the whale himself was a monster.

David Catlin “Moby Dick” (2015) – A Drama

One day not so long ago, David Catlin found himself enthralled by a book he had never managed to find the time to read. Catlin’s professional home is Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre which has become renowned for innovative, acrobatic and viscerally exciting performances. The book he was immersed in was “Moby-Dick”—and “with the help of espresso and NoDoz, I stayed up for 48 hours and read it straight through in an over-caffeinated haze.” Awestruck by the power and the poetry of it, he Moby-binged for days, sleeping not at all.

One day not so long ago, David Catlin found himself enthralled by a book he had never managed to find the time to read. Catlin’s professional home is Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre which has become renowned for innovative, acrobatic and viscerally exciting performances. The book he was immersed in was “Moby-Dick”—and “with the help of espresso and NoDoz, I stayed up for 48 hours and read it straight through in an over-caffeinated haze.” Awestruck by the power and the poetry of it, he Moby-binged for days, sleeping not at all.

When he closed the book, the director came away with a vision of pure dramatic adventure. Construct a whaling ship in his little theater? Why not, my rapscallions? Taking an audience on a whale hunt? Avast, ye maties, let’s give it a go! Imbue the play with witches and fates, waves and towering masts? Take the rudder, Mr. Starbuck!

Indeed, in an era of touring theatrical spectacles such as “Spiderman” and the “The Lion King”—of mind-blowing cinematic CGI and the daring muscle of Cirque du Soleil—what’s a theater director to do? Can a modern audience still be grown and nurtured solely in the ancient soil of proscenium drama? Must a metropolitan theater become little more than a museum of colorized classical plays? How can a director stir up fear and awe and catharsis in a mere modern playhouse, especially in this, our age of eye-opening 3D and ear-popping Surround Sound?

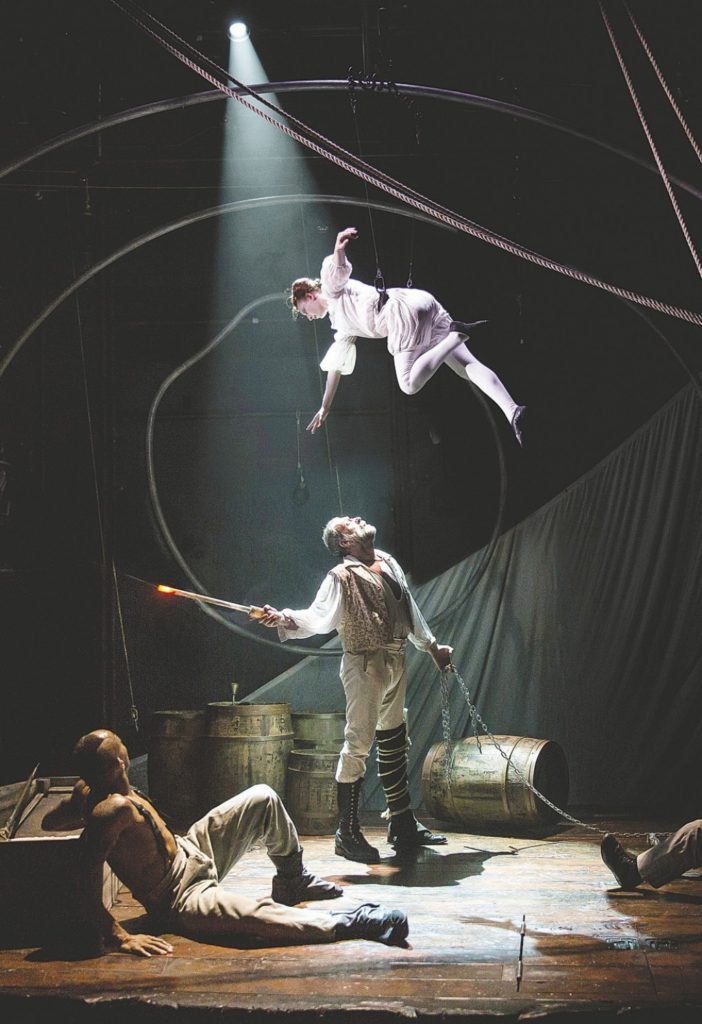

A long period of development ensued. Three Chicago theaters proposed a triad of Moby plays in a summer internship program. Northwestern University agreed to an exploratory production. In the end, for his first release, Catlin partnered with the locally-renowned Actor’s Gymnasium for high-wire choreography of mast-and-rope trapeze work and special acrobatic effects.

A long period of development ensued. Three Chicago theaters proposed a triad of Moby plays in a summer internship program. Northwestern University agreed to an exploratory production. In the end, for his first release, Catlin partnered with the locally-renowned Actor’s Gymnasium for high-wire choreography of mast-and-rope trapeze work and special acrobatic effects.

From the beginning this play unfolds in new and exciting ways. Even before the opening lines, the stage stares eerily across the backlit ship into the darkness of the proscenium. Set upon it are great towers of white that ascend concentrically from each side into the darkness of the upper reaches of this little world—a sort of abstract sculpture that immediately calls to mind the ribs, and the great inside of a whale. Riggings and heavy rope and sails in the form of great silks appear before us also, and descend from the heights as if the stage were also the deck of a decrepit ship.

But the adventure must be told, not simply seen, for it is the story that anchors the drama. Ahab himself has been given a new dimension not seen in the movie adaptations: he is older, facing a confrontation with not only his nemesis Moby-Dick, but in the twilight of life itself. Played with Lear-like pathos and outrage by Christopher Donahue, mercifully all the novelistic elements are adhered to through the characters: the cool majesty of the warrior Queequeg, the spritely naivete of Ishmael, the anguish of the Quaker Starbuck, the sheer blarney of the 2nd mate Mr. Stubb.

The play is part dance, part drama, but also captures the essential Moby-Dick, the muscular prose-poetry of Melville, and the sheer Shakespearean aura of the men aboard the Pequod. The whale hunt is brought chillingly to life, along with the dangers of men overboard, and squalls that arise. The hunting boats swing from rear stage to well over the audience. The towering whale ribs act as great masts upon which the riggers climb like dancers.

And yet the outstanding innovation here might well be the use of women in the cast. Catlin keeps the crew itself all-male, a nod to the novel, but he ingeniously imagines three females in the cast, who mutely represent, in the early scenes, women whose husbands have lost their souls at sea, then fates or harpies or witches that drive Ahab’s ghostly visions, then again the wind and waves in a squall, and, in the final scene druids and spirits of a sea that consumes the whalers, all except Ishmael. As described by one reviewer, this may just be the “feminine tonic” that Lookingglass applied for modern audiences.

And in a masterstroke of adaptation ingenuity, the women also become the whales, floating through the space above, glancing helplessly at the boats, swimming not in the sea but as if in a rhythmic dance of free spirit, high above. This aerial ballet of whales—in stylized hoop skirts, suspended from above—morphs into a whale’s harpooning and slow death. Gradually losing its life in a slow spinning dance, then twirling over and over as the skin is shred, layers of its fabric unfurling, falling upon the Pequod at first in white, then pink, then red—the whale thus gives up its blubber, gathered and boiled in a vat of red-hot burning whale oil, stirred by sailors. Look above, and but a skeleton of hoops remains.

At the end, the horror of plunging into the sea is palpable. Their fates decided, sailors on the masthead dangle helplessly upon the riggings. The sea arrives. The stage disappears. There is nothing but watery silk as each of the men is embraced by the spirit of the sea taking him down with her.

Performances

“Moby-Dick” played several venues over the past two years: Chicago, Atlanta, Washington D.C. and Costa Mesa, California, accompanied by considerable buzz and breathless surprise. Even more amazing is that this memorable adaptation is to be reprised again this year in Chicago—not in one short run, but all summer long. Something tells me word is getting around.

Videos

Lookingglass—Moby Dick

David Catlin

Paintings

A PERSONAL EPILOGUE: THE BOOK

Final question: Is there a possibility today of a parallel between Ahab and a certain vengeful public personage? Is there a sense, as there was on the Pequod, of doom and fatalism amongst the loyal crew? Or perhaps, worse: is there a common zeitgeist in this not-quite-so-fictional, perilous world, a ship cut anxiously adrift, a determined but helpless crew in search for reason in the hands of a demagogue?

Let everyone make their own judgment. The Book is the thing. And it is not a book to crack open when you are young like Ishmael. In our early years it must seem a tome, the rough going ponderous. Fortunately, yours truly was way too busy in his youth reading everything else, and not until my late 30’s did I dare to delve. This past few months, I was on my second voyage.

For a mature reader, the book’s meaty romantic breadth and Shakespearean style can be a thrilling and sumptuous delight. The book is an epic, and it is a tragedy, as well as sort of modern proto-impressionist work, a style I might call digressionist.

So if you have the fortitude for going on this longer voyage, you may wish to consume in small quantities. Melville actually makes that easy. There are exactly one hundred and thirty-five chapters, mostly bite-sized miniatures, meted out as self-contained essays and musings, explanations and meditations—and stories of whaling and sea adventure. It recalls other great epics and tragedies.

- Think “The Iliad”—the story of a great historic battle, but, in form, more of a great quilt made of many stories, many gods and heroes, and what, at the beginning, would appear to be an impossible task.

- Think “Paradise Lost”—the grand design, its many gods and angels of oh-so-human constructs, and most especially its anti-hero Satan, who conceives a plan to rend God’s creation apart in lieu of his own fall from grace.

- Think “Macbeth”—the would-be King whose course is driven not by his instincts but the by machinations of power and the many superstitions and dreams and mysteries that entrance and drive his fellow miscreants to madness—and over which he slowly loses control.

One Response to “An All-New Moby-Dick”

Ironic, the play was so true to the book, compared with the movies/mini-series. It was a stunning production.