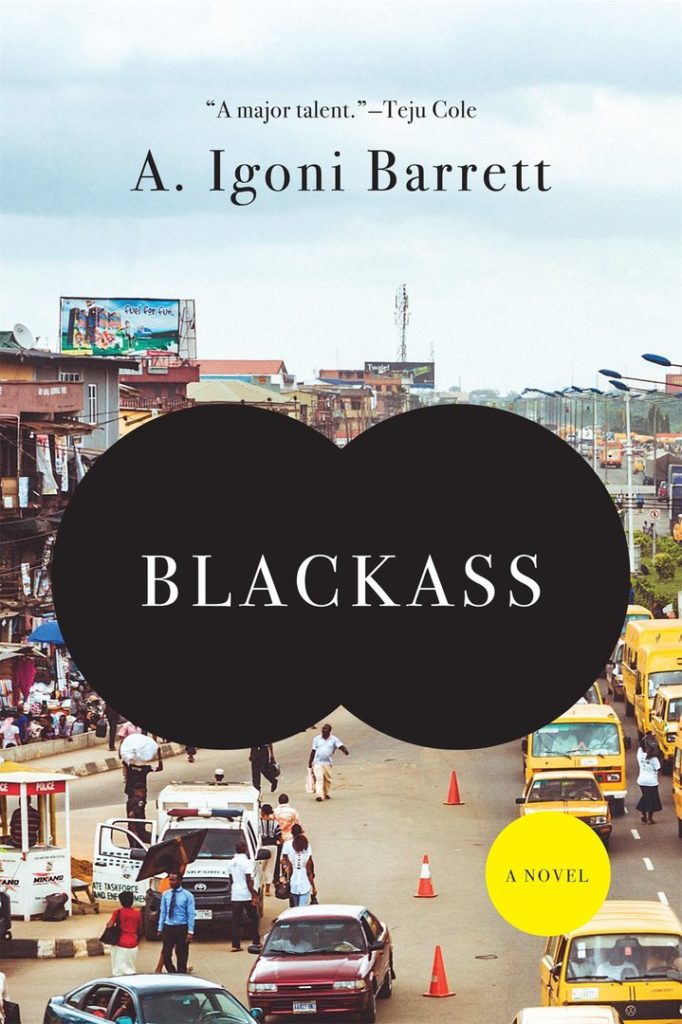

Metamorphosis Redux

A. Igoni Barrett

“Blackass: A Novel” (2015)

Arrrrggghhh! That title!

I know, I know. It explodes in your face. And it begs explanation. For now let it ride. In due time, all will be revealed.

Let us begin, then, as does the storyteller, recounting the dream.

Furo Wariboko awoke this morning to find that dreams can lose their way and turn up on the wrong side of sleep. He was lying nude in bed, and when he raised his head a fraction he could see his alabaster belly, and his pale legs beyond, covered with fuzz that glinted bronze in the cold daylight pouring in through the open window. He sat up with a sudden motion that swilled the panic in his stomach and spilled his hands into his lap. He stared at his hands, the pink life lines in his palms, the shellfish-coloured cuticles, the network of blue veins that ran from knuckle to wrist, more veins than he had ever noticed before. His hands were not black but white … same as his legs, his belly, all of him. p.3

Stay calm, Furo thinks, straining for sanity. Am I still dreaming? He hears the “unruffled buzz of traffic, the whale honks of trailers, the urgent beeping of a reversing Coaster bus …”—then suddenly he is “startled back to alertness” by his phone alarm, and sits up at the edge of the bed.

The pallor of his feet was stark against the rug’s crimson. He was white, full oyibo, no doubt about it. p.4

It is no dream. Everything remains the same as yesterday, and the day before, and the day before that. Except this: it is Furo Wariboko’s first day as a white guy.

Naturally upon Furo’s waking we are immediately reminded of the opening of Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis.”

When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin. He was lying on his back as hard as armor plate, and when he lifted his head a little, he saw his vaulted brown belly, sectioned by arch-shaped ribs, to whose dome the [bed]cover, about to slide off completely, could barely cling. His many legs, pitifully thin compared with the size of the rest of him, were waving helplessly before his eyes. – Translation copyright © 1972 by Stanley Corngold

A stunner for sure, but in this new book we soon realize that Furo is no Gregor Samsa. He, like Gregor, might be a little slow on the uptake, but Furo is a modern, twenty-first century opportunist, and in that sense, he is like everyone else in his home town—the Egbeda quarter of Lagos, Nigeria—a survivor bee in the economic hive of the megacity.

As we turn to page 4 of this book, we might also recall “The Twilight Zone,” which would probably have offered up something like this in the intro:

Meet Furo Wariboko—a hapless, clever, perpetually out-of-work Nigerian—who wakes up in his own bed with the realization that he is now white. To make matters worse, he is running late for his next job interview. In short order, Mr. Wariboko will soon come face-to-face with his past, his present, and his future. For he is about to take his first step … into the Twilight Zone.

I confess that’s a bit underdone—me, your trusted guide, channeling the inimitable Rod Serling—but that’s what we readers do, is it not? We scan our memories for corresponding tales. We seek comfort in the familiar. We superimpose our preconceptions.

Granted, there is a bit of both influences in this opening. Furo lives with his family, his mother and father and sister, in a cramped, modest working-class house—sort of like Gregor Samsa. And yes, he tries unsuccessfully to shake off the transformation as if it were a dream—as he might well have done in “The Twilight Zone.”

Yet we too feel the shock. We read frantically on, as we experience with Furo the nightmarish quality of his transformation. The panic mounts as he gazes into the mirror.

We also discover that the fellow is way ahead of us.

For Furo quickly comes to terms with his possibly-permanent full-body makeover. He wastes no time mulling his fate or his existence. He immediately concludes that he cannot be seen by anyone in the house. That is out of the question. He must sneak out in a mad dash, thinking only to survive, and arrive well-dressed and on-time at his much anticipated job interview. He is late already.

Furo is much more than possessed. He is on a mission. We dive in with him, headlong into his world, into what the normal everyday reality is for Nigerians, navigating the noisy streets of Lagos, scanning for any advantage—all the while sporting a gleaming white facade with a head of auburn hair.

Mind you, Lagos in our century is no sepia-toned photo, no memoirist’s notion of a quaint colonial seaport. Lagos is a roiling mass of economic ferver—pedestrians, buses, cars, litter, smog—a land of traffic tributaries flowing into a great river of people on the move. It is clogged with bodies and noise, not to mention the incessant cacophony of horns and hawkers.

Furo must steer himself along these riverbanks of vendors, the steaming basins at food stands, the myriad displays and canteens and bukas.

The bus stop was crowded with heads and limbs in a swirl of motion, and jostling for space on the motorway were all types of vehicles from rusted pushcarts to candy-coloured mopeds to sauropod-sized freight trucks, all of them vying with pedestrians for right of way. p.11

It is here, in the maelstrom, where Furo’s nightmare transforms itself into contest: tackling obstacles, somehow hurtling the many miles to his destination, and to arrive decently composed and not too sweat-stained at his blessed interview—it is all he can think about—which, by the way, is for a job he suspects he won’t even qualify for. Still, he must soldier on, the opportunity cannot be missed. In some ways, he is thinking: well, if I am destined for a time to be a black man trapped in a white man’s body, so be it.

That, in fact, is the trick of this wonderful book: a kind of literary breathlessness.

* * *

A. Igoni Barrett is a first-rate literary cut-throat. His first book was “From Caves of Rotten Teeth” (2005) and his second, “Love is Power, or Something Like That” (2013). I began reading his stories sometime back, with the same excitement I did long ago, with another line of authors at an earlier time in my life—Balzac, Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Steinbeck, Bukowski—and so many, many others—who might be said to have attempted a breakthrough in their time, as well. Writers making visible a world that is invisible and unseen, and all too often called the underbelly of society.

Word pictures in Barrett’s work are interleaved into the little everyday struggles and sometimes horrors of life on the bottom rung, stories exactingly detailed and at the same time lovingly drawn—even some that are sonically infused with pop and street music. But it is the lives of the people that pick away at our attentions, characters who stay with you. A kind of Pidgin English predominates the dialog. A stench of decay pervades their lives. A ray of dignity might also slip through.

In “The Worst Thing that Happened,” Ma Bille, an aging woman must struggle to navigate the city’s streets to find her way across town to see her grandchildren. On returning, when confronted by an attack dog, she is revisited by a memory that has never left her, when once she accidentally killed five dogs of her own, all together at the same time, with a thoughtless poisoning. In “The Shape of a Full Circle,” Dimié Abrakasa, a boy, has to roam the streets for his mother’s next bottle of whiskey, and returns with nothing for his siblings—as the little bit of money he had was stolen while he secretly hung out for a time with a gang of neighbor kids, kids he had come across standing in a circle, and as he approached, noticing them stoning a “crazy-mad” woman in the alley.

A. Igoni Barrett

The painting of such close-ups from the lives of the dispossessed is a calling. The sadness of any tale can take your breath or send a chill. Barrett’s intimate familiarity with life on the street today is stunning. He knows the people, he knows the policemen, he knows the landlords and the barmaids. His descriptions, both in his stories and his novel, often swell gradually. Graced with wincing detail and clashes of social caste, they are told in a rhythm of raw poetic beauty. In the selection quoted below, three policemen—out on a lonely road late at night and bored out of their skulls—go looking for easy money.

Eghobamien Adrawus saw a shimmer in the distance. It grew bolder, became a glint. By the time it collected into two halogen orbs that arced through the darkness, he and the other policemen had taken up their positions. Mfonobong flicked on his torch, stepped into the path of the vehicle, and waved the torchlight with the wrist motions of a fly fisherman. At what seemed the final moment, the car braked with a screech of tires. It stopped within a hand’s breadth of Mfonobong’s knees. It was a black Toyota Avensis with a customized plate that spelled “EGO-1.”

The hand in this story might well be the hand of Barrett himself, reaching for the next rung on the ladder. Perhaps even a bridge to this novel we are continuing to explore.

* * *

Furo is needing to check the time. Damn, his pocket is empty, he has forgotten his Blackberry, his first UH-OH moment. Worse, he has no choice but to keep speed-walking, for he has no car (of course) and no money (he had meant to ask his father) and now he is utterly without contacts. Still, he does not stop to think, how can I proceed? He knows he must proceed, undeterred. If nothing else, he has his one suit of clothes on his back, his plastic folder under his arm, and inside that folder, his resume. He has passed the point of no return. He is fully committed to the absurd notion that he cannot go home now, and yet seized with the idea of an unknown outcome.

OK, so what if he is a white man? Full oyibo, as they say? Sure, hard to swallow, but he must leg it out. Early on, he frightens a little girl at her mother’s side. This disagreeable fact is merely the next challenge. How to appear as if nothing has happened? How to ignore all the stares, all the roadblocks that he must now maneuver?

The race is on. Suddenly Furo, still out on the street and sighting a far-off highrise gleaming through steamy skies, now realizes that he has “misjudged the distance.” Yesterday the family had planned for his father to give him a ride, an impossibility now. Out on the street, no one recognizes him, thank God, but this morning he has been a curiosity, the focus of every native Nigerian on the street.

The terrain is, to him, familiar territory—road drainage clogged with market litter, umbrellaed shops and lean-tos selling everything from “live catfish, dead crayfish … pirated CDs and Nollywood VCDs”—but obviously a place no whites would normally be seen, at least walking out on the street. Furo for now is “the lone white face in a sea of black”—but thank God, no one has yet recognized him.

Instead, the buka owners and food sellers call out, “Oyibo!” and he quickly adjusts, learning to “act white”—standing straight, eyes down—but the problem is that inside, he is still Nigerian. He cannot speak English in any accent other than his own.

He must stop and ask a woman on the street for the time of day. She laughs, and tells him her name. Unused to such unearned informality, he returns the courtesy. Then she inquires, cunningly, why does he have a “Niger Delta” name? She notes his accent. Quickly he sidesteps the issue, he pleads that he has an interview, it is getting late, he needs money for a taxi. He makes up a story that he was attacked by robbers who took not only his phone, but his car. “I was lucky to get away with documents,” he says, tapping the plastic folder under his arm. And with that—with this first, tiny little sackful of lies—the strange white guy on the street lands a thousand-naira note, about three dollars American, not much, but enough for the cab fare.

The building at which he arrives is more like a compound. It turns out there is only one sales job available. Standing at the back of the line with forty others, Furo at last senses a sea change in the way people look at him up close. Everyone seems to notice that he is, yes, full oyibo. The woman next to him gives him the evil eye. The guard on duty tells him about his brother’s immigrant status in Poland, hoping Furo could intervene for a letter of transit to that country. “I like you. You don’t talk through your nose like other oyibo.” When Furo enters the office to sign up for the interview, the astonished receptionist embarrassingly drops her pen. Quickly she makes a phone call. She directs him to come with her.

So it is that our newbie-white guy with a Niger Delta name is fast-tracked into the office of the president, of all things, a well-dressed Nigerian honcho named Ayo Abu Arinze. But even in the brief transition, whilst waiting in Human Resources, Furo has drawn undo attention to his name and nationality, and about the latter, the staff are completely unbelieving. How ridiculous! How can an oyibo man be named Wariboko?

Fortunately, Mr. Arinze steps in and ably removes him from the questioning. Furo’s resume has scarcely been reviewed. No matter. Sitting opposite Arinze in the boss’s spacious office, Furo is calm and a little nervous, but prepared. The man looks him straight in the eye.

“I’ll be frank—we need a man like you on the team.” p.25

Furo, now dizzy with good fortune, seems not to notice his little lies are mounting up. Even so, he has become the only white on the staff. He will start working in a week. No one knows he has no money, no phone, and no clothes other than the suit on his back. Further, though Arinze has offered him what seems like a fortune, and a future with benefits, he is told he needs a passport as well.

He will make it work. He would have his new boss believe the old passport is long expired. He seems little by little to be getting accustomed to the fibs, like making a minor down payment for his good luck.

It is afternoon when he leaves the compound. Following a meal, he has only a few naira left.

He couldn’t afford a hotel, and police stations were to be avoided. He would most likely be arrested as a foreigner with no papers… Even churches had learned the hard way that robbers in Lagos had no fear of the Lord. (p.36)

He hunts down a building—any entirely abandoned building will do, away from the crowds. He cannot take a chance on the street, and he cannot go home. No question his mother would think this was all black magic. No doubt she would take him to consult with the spiritual healers.

The next day Furo’s brain explodes with scheming, carving a future out of this turn of events. With ninety naira in his pocket, he boards a bus for the white part of town. He devises a plan to enter the land of the rich businessmen, in particular at “The Palms,” a shopping center and mall where at least there was free air conditioning. Even on the bus to the mall he is the object of some fascination. The fuzz on his arms “seemed to change colour from red to orange in the slant of sunlight” and his nose now “smarted from sunburn.” (p.46)

It is in the mall where things take a turn for our desperately privileged wanderer. He is no longer stared at. He is waited upon for a coffee. And not surprisingly, he is singled out by a high-class black prostitute, the sexy Syreeta, who takes him up the elevator to a secluded nightclub, and from there to her gated community (“a fortified Eden”). She has, he discovers, a rich boyfriend who obviously pays for her apartment, but oddly Syreeta is focused only on Furo, dotes on Furo, is enchanted by Furo, and quickly promises a massage to salve his evident weariness: “I am good with hands. And my house is not far from here.”

The next morning they talk. Unaccountably she even allows him the opportunity stay with her awhile. Merely good fortune? Is he becoming indebted to her? No matter, she lays out rules. They nuzzle up. He rises to prepare.

Through the window above the fridge he saw the morning face of the sun suspended in the cold-coloured sky, and behind him he heard Syreeta tumble into bed. Then a muffled scream punched the air, and Furo whirled around to find Syreeta staring. She raised her hand, pointed a stiffened finger at his groin ….

He glanced down in fear. ‘What?’

‘Your ass, your ass!’

Furo spun around, saw his reflection; then turned again and looked over his shoulder.

‘Your ass is black!’ Syreeta cried, and as Furo stared in the mirror, frozen in shock, she flung up her arms, flopped on her back, and wailed with laughter. p.74

* * *

Now that, my friends, is one very serious Achilles’ heel. Or perhaps just another nod to the classics?

And the title too, which at first seemed so unseemly, is at long last endowed with meaning. Perhaps even riven with meaning. For Furo is never really full oyibo; he is but a black guy in the guise of his white skin. His performance is both comedic and hypocritical. Perhaps if Barrett had been looking for kinder reviews, or seeking fuller acceptance from his fellow Nigerians, he might not have pushed the knife in quite so deep. He might have gone easier with the title. But good writers, as they say, don’t play to the audience.

Anyway, here we are at page 75. We have another 200 to go. Far be it from me to ruin the joy of the remaining read, let alone the ending. The sheer acrobatic athleticism of Barrett’s prose provides a corrective to the “good life” of Furo Wariboko who now seems more like an escape artist than a man on a mission. He dons a much-needed name change. He encounters the perils of official bribery. He barely dodges his sister’s hunt for him on social media, and he takes bigger and bigger job offers from every businessman he runs into—not to mention the ever-present danger of hiding the truth from savvy taxi-drivers and nosey Nigerians who eternally ask, how-come-you-know-Pidgin?

The great satirist Tom Wolfe always wielded, not so much a sword, but rather a simple premise: everyone has a price. And while most everyone in this book is simply covering their own ass, slyly or secretively, Furo is hell-bent on avoiding discovery. He doesn’t seem to question the sanity of the incessant and necessary hoops he must jump through, including the unsuccessful attempts to whiten-up his … uh … Achilles’ heel. Towards the end, he can hardly stand to sit.

And what comes of his flame, Syreeta? Well, she may not be a keeper, but at the novel’s end, at long last Furo discovers just why she took him in. Sorry, no reveal here. The ending alone is a mind-blower well worth the price of admission.

Leave a Reply