The Library Chronicles

We may not all be scientists, but many of us do know some odd scientific factoids.

Ray Bradbury in his 30’s

For example, the temperature at which paper burns. We know this because in 1950 Ray Bradbury had an idea for a book. A perpetually-underpaid scribbler for a long list of popular and sci-fi magazines, Bradbury wanted to pitch his novel idea. He drove from Los Angeles to New York, took a $5 suite at the YMCA, and went a-knocking door-to-door on publisher row.

His hopes, however, were soon dashed. The problem? Most publishers needed a book now, and Bradbury didn’t have one.

But before he could leave town, Bradbury dined with an editor from Doubleday who offered a compromise. They would be willing, he said, to go forward with a book of his published stories, but marketed as if it were a novel. The book would be a patchwork of glimpses into a dark future, with a focus on the colonization of Mars near the end-times for planet Earth. His editor even offered a title: The Martian Chronicles.

Bradbury was relieved. He accepted the offer on the spot—and the title too—for after all, he seriously needed a foot in the door. But that “fix-up” wasn’t really what he had hoped for. The clock was ticking; the idea wouldn’t stop nagging. On the other hand he had no choice but to continue supporting his family writing mostly short stories. He went to work on the “real novel” whenever he could find the time.

He used some old manuscript pages stashed here and there, and interleaved notes that he had jotted down over the years. He developed a new take on an old theme: a dystopian society that had been co-opted by an ever present electronic mass media, an oppressive state where books were outlawed and book burning had become officially sanctioned.

The working title was “The Fireman.”

When two years later he finished the book, he headed over to the UCLA library. In a room in the basement, where the public could rent typewriters for 10 cents an hour, he hammered out the manuscript from his handwritten original. He paid the librarian $9.80.

Before submission, though, there was one lingering doubt. Bradbury never really liked his working title. And he certainly didn’t trust a publisher. He knew he must come up with a ringer—a title that no editor, no publisher could turn down.

So on a whim, he called the Los Angeles Fire Department and asked one simple question: What is the temperature at which paper burns? The answer: 451 degrees Fahrenheit. The year of publication: 1953.

It is a strange and sterile little world depicted in Bradbury’s now-classic novel, where everyone is told how to think and what to say by disembodied voices on their radios and television sets—brainwashed, as we used to say. There are no bookstores, no public libraries. There are only private, secret libraries. And when an old woman is found to have books illegally stashed away in the walls and floorboards and the attic of her old house, she chooses to die among her many cherished volumes rather than be imprisoned, or worse. The fire officials throw the books into a great pyre in the center of her house, and torch it. The sheer horror of that scene, both as described in the book and as depicted in the film (1966), speaks of a dedication beyond modern comprehension. As the flames rise around her, as the books burn and shrivel and dissolve into ash—we are left not a little shaken, and just this side of breathless.

It is a strange and sterile little world depicted in Bradbury’s now-classic novel, where everyone is told how to think and what to say by disembodied voices on their radios and television sets—brainwashed, as we used to say. There are no bookstores, no public libraries. There are only private, secret libraries. And when an old woman is found to have books illegally stashed away in the walls and floorboards and the attic of her old house, she chooses to die among her many cherished volumes rather than be imprisoned, or worse. The fire officials throw the books into a great pyre in the center of her house, and torch it. The sheer horror of that scene, both as described in the book and as depicted in the film (1966), speaks of a dedication beyond modern comprehension. As the flames rise around her, as the books burn and shrivel and dissolve into ash—we are left not a little shaken, and just this side of breathless.

Susan Orlean

“The Library Book” (2018)

Susan Orlean

Private or public, libraries are not ordinarily burned for money. In fact there is no money to be had, as Susan Orlean attests. Libraries are intentionally burned for the same reason that public book burnings take place—because “books contain ideas that someone finds problematic.” (p.97).

The first known book burning was in China in 213 B.C. The ancient library in Alexandria, Egypt was burned at least twice, once by Caesar in 48 B.C., and again by the Turks in 640 A.D.

When Caliph Omar, who led the Muslim invasion of Egypt, came upon the library, he told his generals that its contents either contradicted the Koran, in which case they needed to be destroyed, or they supported the Koran, in which case the were redundant. p.96

In thirteenth century Italy, the pope ordered Jewish books to be “cremated.” In the 1500’s, following the Aztec conquest in the New World, the Spaniards burned every Aztec scroll and Mayan book they could get their mitts on.

Things actually worsened in the 20th century. The 1930’s in particular were a book-burner’s paradise. Books were “sentenced to death” at the Nazi “Fire Encantations” of Joseph Goebbels. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao—having been an assistant librarian in his early life—ordered the purge of any books that espoused old ideas and customs. The libraries of Tibet were “cleansed.” Almost two hundred libraries were burned during the Bosnian War. The Khmer Rouge destroyed, fireman-style, over 80% of their National Library.

Things actually worsened in the 20th century. The 1930’s in particular were a book-burner’s paradise. Books were “sentenced to death” at the Nazi “Fire Encantations” of Joseph Goebbels. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao—having been an assistant librarian in his early life—ordered the purge of any books that espoused old ideas and customs. The libraries of Tibet were “cleansed.” Almost two hundred libraries were burned during the Bosnian War. The Khmer Rouge destroyed, fireman-style, over 80% of their National Library.

Orlean offers an explanation: books represent the life blood of a culture. Without books, we are without civilization. The vanquished are indeed rudderless.

Books are a sort of cultural DNA, the code for who, as a society, we are, and what we know. All the wonders and failures, all the champions and villains, all the legends and ideas and revelations of a culture last forever in its books. Destroying those books is a way of saying that the culture no longer exists; its history has disappeared; the continuity between its past and is future is ruptured.

p. 102-103

Orlean cites a disturbing fact: most library fires are deliberately set. And yes, it happens still. Even … here.

Central Library, Los Angeles

April 29, 1986

It was a blue-sky day in downtown Los Angeles. The air was crisp, and the morning seemed to have a bounce in its step. Fresh westerly breezes had prevailed overnight to break the heat of the previous day.

For the librarians at Central Library, it was just another quiet Tuesday. Their once-flashy building was a classic stucco straight out of, well … yes, Hollywood. Built in 1926, it had made it through many years hale and hearty. And though now aging, and a bit too crammed with books, it was still nestled at 659 W. Fifth Street in the midst of all the modern glass and steel you could cram into a city block.

But Central Library, as Susan Orlean points out, also stands apart from sultry Hollywood mansions of the 30’s and 40’s—displaying, even today, such majesty that it “manages to look ancient and modern at the same time.”

The building—buff-colored, with black inset windows and a number of small entrances—is a fantasia of right angles and nooks and plateaus and terraces and balconies that step up to a single central pyramid surfaced with colored tiles and topped with a bronze sculpture of an open flame in held in a human hand. -p.13

There the statuary held forth, inside and out: here a Socrates casting an intimidating gaze, there a marble woman and her trident forming the Statue of Civilization. There was “bas-relief on every wall,” and even a rotunda where our little blue planet hangs from a pendulum.

The Rotunda

The doors, as usual, opened at ten o’clock sharp. Over the first hour of the day, hundreds of patrons entered and settled into their routines: reading, writing, searching and researching, or perhaps just lounging in the available seats.

But then, a few minutes before 11 a.m., the fire alarm went off. Patrons and staff sighed, and for the regulars it was obviously not the first time. Folks arranged their materials, dutifully rose from their seats and began making their way out to the street—calmly for the most part. Some rolled their eyes. Others left their belongings in place so they could return without much bother.

Once outside, the librarians took the opportunity to light up a cigarette, chat, check out the latest scuttlebutt from the other departments—generally finding some way to bide their time while waiting for the all-clear to be announced. For one must remember that this era was way before our time. Before iPhones and news feeds, you see, there was little more than small talk to fill the spaces.

What’s not to like? Enjoy the good weather! Soon the fire engine would arrive. And the firemen, as usual, would find nothing wrong, and would simply reset the alarm.

Out on the street, though, a curious sight was unfolding: more than the typical number of fire trucks were appearing on the scene. The seconds kept ticking away. And the minutes. And as the time continued to pass, and the conversations dwindled, the mood was growing more and more somber.

A steady stream of bystanders trickled in, mostly from office buildings in the area. Within minutes, more and more fire trucks arrived. The firemen entered the building hurriedly; as others arrived, the replacements took up positions on the street in support of their fellow firefighters inside the library.

So this was getting serious, or was it? And where was the fire? What was all the fuss about? For the first hour, from the outside, the building itself seemed impervious, impassive, “cool as satin.” If there was really a fire inside, the fact was utterly unknown to the outside world.

Eventually a sign appeared. A visual manifestation. It was a fizzle of white smoke seeping from the upper floors. From the outside it seemed devastatingly quiet, a long-dreaded turn of events. And yes—surreal. A sign not so much from the heavens but out of the movies. And with that came the cold, quiet realization amongst those in the crowd that something far more serious was indeed in the offing.

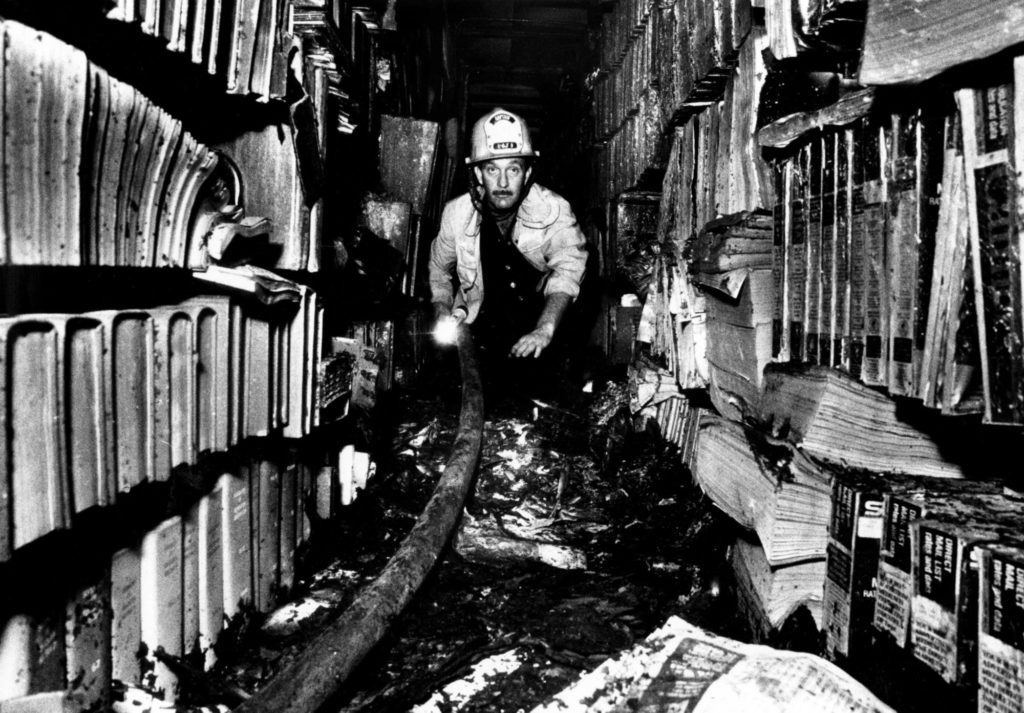

Truth be told, inside there was chaos. The fire had started in the stacks, and the radiant heat had been mounting quickly. Furthermore, once in the stacks, the firemen had no radio communication. Their signals were blocked by concrete walls that were three-feet thick.

Truth be told, inside there was chaos. The fire had started in the stacks, and the radiant heat had been mounting quickly. Furthermore, once in the stacks, the firemen had no radio communication. Their signals were blocked by concrete walls that were three-feet thick.

The library was organized around four book “stacks,” a method of library storage invented in 1893 for the Library of Congress. The stacks at Central were narrow, freestanding vertical compartments—essentially, big concrete tubes—that ran from the basement to the ceiling of the second floor. Each stack was divided into seven tiers by shelving made of steel grating. The open weave of the shelves allow air to circulate up and around the books, which was considered beneficial [in preventing mold]. -p.22

But within two hours that once-upon-a-spark was now morphing into a heat monster, growing in intensity. As the water from the hoses cascaded down the floors inside the building, the flames rose higher and higher, and leapt from stack to stack. In that kind of heat, the streams of water from the fire hoses, even under high pressure, began to evaporate. And all this, even as the resources of the L.A. Fire Department were being drained to over half of their fire stations.

Still nothing much on the outside—until this happened—as seen by observers on the sidewalk.

Suddenly, with a bright, hard snap, the windows on the west side of the library exploded and red arms of flame punched outward and upward, slapping at the stone façade. One of the library commissioners watching from the sidewalk burst into tears. -p.29

What on earth was happening? Had not everything seemed so placid that morning? So utterly normal? So perfectly pacific?

Simply put, the stacks—a sort of building inside the building—were becoming an inferno. Even the great stucco structure itself began to quiver. The stacks were so perfectly funneling the fire and the heat from one stack area to another, and from one floor to another, that in a few short hours the hellish blaze was transformed to the level of a rare “chemical phenomenon known as a stoichiometric condition, in which a fire achieves the perfect burning ratio of oxygen to fuel … Such a ratio results in total, perfect combustion” (p. 25)—destroying everything in its wake.

The temperature reached 451 degrees and the books began smoldering. Their covers burst like popcorn. Pages flared and blackened and then sprang away from their bindings, a ream of sooty scraps soaring on the updraft. … The fire scrambled to the sixth tier and then the seventh. –p. 23

And then the fire “found a catwalk that connected the northeast stacks to the northwest … until it reached the patent collection. … so thick they resisted but the heat gathered until at last the gazettes smoked, flared, crackled, and dematerialized” (p. 24). The fire created wind gusts, fractured floors, and when it reached 900 degrees the steel shelves “brightened from gray to white, as if illuminated from within, twisting, slumping, pitching their books into the fire.”

By around 2 p.m., the temperature had jumped to 900 degrees. By 3 p.m., 2000 degrees. Not long after that, 2500 degrees. Yes, Fahrenheit. The color of the fire was eerie: not red, not orange, not yellow—but colorless. The firefighters had no choice but to retreat. One of them interviewed later said the men felt as if they were standing in a blacksmith’s forge “looking at the bowels of hell.” (p.25)

By around 2 p.m., the temperature had jumped to 900 degrees. By 3 p.m., 2000 degrees. Not long after that, 2500 degrees. Yes, Fahrenheit. The color of the fire was eerie: not red, not orange, not yellow—but colorless. The firefighters had no choice but to retreat. One of them interviewed later said the men felt as if they were standing in a blacksmith’s forge “looking at the bowels of hell.” (p.25)

In a last-ditch effort to vent some of that heat, a special team was called in to jack-hammer the concrete walls open. Each opening provided some relief, but the fire had its own grim mission to accomplish. Eventually the firefighters hammer-punched through the roof and at that point the furious inferno seemed to have consumed most of its fuel, apparently dying of its own inner physics. Towards the end of this horrific fight, the flames finally yielded to the “torrents of water and to the cool air that was wafting through the holes jackhammered through the ceiling and floors.”

The fire pulled back from the southeast section of the building and curled up in the northeast stacks, where it glowered angrily, feeding itself book after book, a monster snacking on chips. The fresh April air mingled with the smothering heat inside, easing the temperature down bit by bit. As the fire shrank, firefighters dug deeper and drenched it. …

The books in the northeast stacks were crumbles, ashes, powder, and charred pages heaped a foot deep. The last flags of fire fluttered, seethed, settled, and finally died. p.30-31

The unthinkable had transpired.

Epilogue

The fire was, and still is, not well known. The news of it was upstaged that day by the explosion of a nuclear plant in a remote place called Chernobyl. The following day, there was even more bad news: the biggest single-point loss in the history of the American stock market, triggered in large part by the resulting cloud of radiation spreading over Eastern Europe.

To this day, you can pick an older book off the shelf at Central, hold it up to your nose, and (they say) smell the fire, the ashes, and the ghost of history in the creases of the pages. It seems odd, but the pleasure of reading “The Library Book” somehow makes up for the horrific scenes. Susan Orlean, a staff writer at the New Yorker and author of several other notable books, including “The Orchid Thief,” spins a terrific anecdotal history of this unique library.

What was lost, who started the fire, how the library came into being from its humble, almost Wild West origins, and especially how the many books and records, sopping wet from firehoses, were frozen, dried, and resurrected—such are among the many stories of interest in this Library Chronicle.

SOME final tidbits

- All the books in the Fiction section from “A” to “L” were burned utterly to ashes. Among the victims: every novel and story collection by Ray Bradbury housed at the Central Library.

- Bradbury always said he was educated in the public library. His parents could not afford to send him to college, so got his own education … yes, in the stacks.

When I graduated from high school, it was during the Depression and we had no money. I couldn’t go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years. – Gutenberg.Org

- Bradbury had long resisted the conversion of his work into electronic form. But in 2011, a year before his death, he permitted the e-book publication of “Fahrenheit 451” provided that the publisher, Simon & Schuster, allow the book to be digitally downloaded by any library patron.

One Response to “The Library Chronicles”

This is a fascinating story. I had never heard this before,