The Re-Framing of the Shrew

Elizabeth Taylor as Kate

End of summer, hanging with friends, sipping beer, casting about for something to do.

One of us notes that every three or four years our local repertory company brings “The Taming of the Shrew” back for another round of braggadocio, insults, off-color jokes, Elizabethan folderol, wisecracks, and finger-wagging nonsense.

And why not? Fabled Kate! Impossible Petruchio! Even here in our fair Atlanta their eternal combat rages on!

I look ’round. Eyebrows lift in consideration.

But I ponder why theatergoers never tire of this classical if somewhat lowbrow battle of the sexes. A knotty little problem, for it has oft been described as misogynist, sexist, or worse. Have we not acquired a tolerance for historical incorrectness? On the other hand, has not our world become a society of Kates and Petruchios? Seems today we live in a place where it is all-the-rage to … well, rage.

The truth may be that this old-fashioned, utterly out-of-date and irreverent play has never been more up-to-date, relevant and popular, either in its original form or in its many adaptations.

But why is that? We aim to answer that very question. Truly, this is a farce to be reckoned with.

William Shakespeare “Taming of the Shrew” (1591)

It once was common knowledge—nay, a surety—that there were certain ill-tempered women to be avoided at all costs: the scold, the battle-axe, the harpy—to name a few among several variants of stock characters that populate folklore and storytelling.

It once was common knowledge—nay, a surety—that there were certain ill-tempered women to be avoided at all costs: the scold, the battle-axe, the harpy—to name a few among several variants of stock characters that populate folklore and storytelling.

But a shrew? Really?

Tut! Tut! Hold enough! An “irksome, brawling scold” is nothing to be afraid of—so boasts the swaggering Petruchio, who has just arrived in Padua from Verona.

PETRUCHIO

Think you a little din can daunt mine ears?

Have I not in my time heard lions roar?

Have I not heard the sea, puffed up with winds,

Rage like an angry boar chafed with sweat?

Here is a man’s man—an adventurer of great accomplishment who doesn’t mind spitting it out for anyone who will listen. In mock earnest he is searching for a wife befitting his station. Which means a woman who qualifies money-wise. When Petruchio hears of his potential boon—her father Baptista promises half of his estate—he jauntily signs on to become our frightful Kate’s suitor.

But aye, here’s the rub. This “Katherine the curst”—this one of “scolding tongue,” “this wildcat”—is early-on found seething. And she perhaps has a right (she and her sister are essentially being bought and sold, after all), but, egads! the way she goes about it! She ties the hands of her sister—the good sister, the beautiful and coy Bianca—she even confronts her father Baptista, accuses him of favoritism, and vows revenge for his cynical decision to give her away to the highest bidder.

KATHARINA

What? Will you not suffer me? Nay, I now see

She is your treasure, she must have a husband;

I must dance barefoot on her wedding day

And for your love to her lead apes in hell.

Kate was not new to Shakespeare’s audience. Meaning, she had prototypes. Tales of wife-taming go back centuries in the folkloric tradition. Stories come from ancient Italy, the northern climes, even Chaucer. Scholars surmise that the rudiments were well known to the audiences of the day: a shrewish, impossible woman who must be bound to a husband all the while behaving most brutishly towards the man. When Samuel Johnson added “shrew” to his “Dictionary of the English Language” (1755), he defined her as such: “a peevish, malignant, clamorous, spiteful, vexatious, turbulent woman.” The only trait that dear Samuel leaves out, our dear William deftly provides: “brawling.”

The truth is, in the play we actually get not one but several alternate views of Kate. In our first encounter, Act 1 Scene 1, she and her father and sister Bianca are discussing their prospects with some oddly-clad suitors of Bianca’s, and happen to be overheard by a university-bound student named Lucretio and his servant Tranio.

After observing a somewhat rough encounter and a nasty give-and-take between Kate and her sister, we hear this:

TRANIO [aside to Lucentio]

Husht, master, here’s some good pastime toward.

That wench is stark mad or wonderful froward.

And the meaning of this phrase “wonderful froward”? Well, as it rolls off the tongue of this one Elizabethan playwright: deliciously perverse. “Froward” by itself was a commonplace word stemming from Old English, literally meaning “willfully contrary.” And yet it is used over and over again in this play as if it were nothing less than a compliment. (Of course, Protestants had their own take, to judge from the not-quite-as-yet-published King James version of the Bible (1611): “Frowardness is in his heart, he deviseth mischief continually; he soweth discord.” (Proverbs 6:14).

So Kate is rather wickedly sinister, and more than a mere handful. Far more than a run-of-the-mill “froward” shrew, that’s for sure. There is a devilish style in her jousting, she has surgical wit, and is churlishly snide at that. No doubt she strikes the audience as oddly beguiling and justified. Perhaps even lofty at times.

At their first meeting Petruchio takes the high road. He throws out absurdly amorous, and clearly insincere, adorations. He tells Baptista that his daughter is “modest as the dove” and “temperate as the morn.” Kate, once alone with her suitor, insists on being called “Katherine;” he insists dubbing her “Kate.” She calls him a “madcap ruffian”, he returns the volley with a whiff, calling her “gamesome” and “passing courteous” and “gentle” and “soft and affable”—all clearly lies, and Kate buys none of it. She goes for the jugular.

PUTRUCHIO

Come, come, you wasp, i’ faith, you are too angry.

KATHERINA

If I be waspish, best beware my sting,

PUTRUCHIO

My remedy then is to pluck it out.

KATHERINA

Ay, if the fool could find where it lies.

PUTRUCHIO

Who knows not where a wasp does wear his sting?

In his tail.

KATHERINA

In his tongue.

PUTRUCHIO

Who’s tongue?

KATHERINA

Yours, if you talk of tails, and so farewell.

Seeing he has met his match, Petruchio stalks off, leaving her to brood about the arranged marriage over which she has no control.

In the next scene we discover that Petruchio hath deviseth a new plan. He purposely arrives late to his own wedding. His absurdly costumed entrance is a well-planned humiliation for the reluctant bride-to-be, and while at first shocking, it is in the end hailed as raucously genius by most of the attendees.

Then, following the vows, he purposely announces he is not staying for the reception. He intends to take his leave with his new bride immediately. He not-so-gallantly says his goodbyes to all, and in doing so stakes his claim to the superiority he must now exercise. All is done in a brusque, knock-off manner intended to publicly humiliate his newly wedded wife. As he departs, he wrestles Kate to his side, and crudely announces to the wedding-goers that he cares not for their opinions, anyway—so much better to show the shrew who is boss, now.

Then, following the vows, he purposely announces he is not staying for the reception. He intends to take his leave with his new bride immediately. He not-so-gallantly says his goodbyes to all, and in doing so stakes his claim to the superiority he must now exercise. All is done in a brusque, knock-off manner intended to publicly humiliate his newly wedded wife. As he departs, he wrestles Kate to his side, and crudely announces to the wedding-goers that he cares not for their opinions, anyway—so much better to show the shrew who is boss, now.

PETRUCHIO

Carouse full measure to her maidenhead,

Be mad and merry, or go hang yourselves.

But for my bonny Kate, she must with me.

I will be master of what is mine own.

She is my goods, my chattels; she is my house,

My household stuff, my field, my barn,

My horse, my ox, my ass, my anything;

And here she stands, touch her whoever dare.

– Scene 3, Act 1

Amid the bravissimo here, we sense in Petruchio a sudden chill. Will she submit to his indomitable will? This worry he must not admit. As the newlyweds take their leave for Verona, there are doubts even amongst the revelers.

For the sake of brevity, we must here neglect the subplots, intrigues and devices that pile on, and feverishly fill out the zany world of Padua. No one can forget the love-starved Lucentio, ridiculously smitten by Bianca at first sight, and, for a shot at becoming her “tutor,” trading clothes and his own identity with his stupid servant Tranio. And on and on, Hortensio and Baptista and numerous others—each in their devious turn looking for wives to purchase, or deals to secure.

A later play, “Much Ado About Nothing” (1598) takes many of these same character types and subplots and delivers a livelier and more everlasting comedy—and interestingly, more modern and self-reliant female leads. But in “Taming” Petruchio must have his way. On the trip to Verona he resorts to pushing and dragging Kate to extremes, riding horseback in a driving rain, not saving her from a fall into the mud, and when arriving at his own house, Petruchio stomps in and rages like the storm and calls upon his servants to make an even bigger mess of things. All with the intention of making Kate miserable and subservient. His wiry and insouciant servant Grumio is but the comic lead among a host of outlandish servant-outlaws that serve the estate.

The Verona scenes alternate with those in Padua, the subplots sub-thicken, the jokes keep coming, and the flaky characters reprise their non-stop monkey-business. Kate still gets her knocks in, here and there, and maintains some sullen self-respect, but even then she is left reeling from Petruchio’s rather painful disciplinary tactics. After she has been dragged through the mud, starved of food, made to beg for a well-tailored gown deemed by Petruchio not worthy of her wearing, she finally … reluctantly … relents. She is forced to acknowledge, if only cynically—if only to survive—Petruchio’s place as master and ruler of her world, of his domain, and of all that he owns. For some reason, all are coming round.

PETRUCHIO

I say it is the moon.

KATHARINA

I know it is the moon.

PETRUCHIO

Nay, then you lie. It is the blessed sun.

KATHARINA

Then, God be blest, it is the blessed sun.

But the sun is not when you say it is not,

And the moon changes even as your mind.

What you will have it named, even that it is.

And so it shall be so for Katherine.

– Act 4 Scene 5

So why was this play not called “The Shaming of the Shrew”? Petruchio forces Kate to accede to him in every respect, even when he is purposely wrong. True, in this uber-patriarchal world, she has no choice. If he calls the Sun a Moon, she must follow. If he calls a Man a Woman, so then it must be thus.

Yet it is in this give-and-take that Kate is finally seen as wavering. We are amused, and at the same time not a little annoyed. Nothing is what it seems? Everything must be acknowledged otherwise? But all for what?

Thus begins Kate’s descent into a shocking but brave submission.

Franco Zeffirelli “The Taming of the Shrew” (1967)

As a young man I knew full well the variations of our theme here: the sourpuss women from church, the surly wives of military colonels, the humorless-mothers-of-many-brats that graced our suburban neighborhood. What we all knew as old biddies.

We did keep our distance. But never, never in my life had I met such a froward, full-throated shrew.

At least not until 1967, when the movie burst upon the scene. Somehow after that, it all made sense. From my own teenage/male vantage point, I completely understood how once there walked among us a type of woman, who, being unremittingly hateful and unaccountably querulous, must of course be tamed by husband/mate/owner/master—or else.

Else what? Else that he and all others in his sphere of influence would be reduced to faltering, quivering, spineless wimps? Yep, something like that.

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton—following the phenomenal success of “Cleopatra”(1963) and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” (1966)—had seemingly been waiting for this moment. In their rip-roaring “Shrew,” these two outsized actors renewed for us their own tempestuous marital vows, and broad-brushed for us their own oh-so-public marital battles, blazed anew. Audiences howled at the schtick. Purists sighed.

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton—following the phenomenal success of “Cleopatra”(1963) and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” (1966)—had seemingly been waiting for this moment. In their rip-roaring “Shrew,” these two outsized actors renewed for us their own tempestuous marital vows, and broad-brushed for us their own oh-so-public marital battles, blazed anew. Audiences howled at the schtick. Purists sighed.

Still, a new era needed this change. Shakespeare was back. And if the movie was over the top, and even if the slapstick was lathered on, so what? A new generation of theater enthusiasts was primed for the gusher. Once the camera makes its way to Padua, Kate opens her scene with an improvised fit of explosive and violent and irrational rage not often seen on any screen—befitting Taylor’s fearsome reputation. Petruchio himself is flagrantly haughty and remains well-sauced throughout, no doubt helped along by certain of Burton’s daily indulgences. The movie is lush and burly and profane and wonderfully engaging, and most memorably recreates Kate’s misery at the wedding vows and her nightmarish, muddy ride back to Verona—two scenes that in the play are only rendered through dialog.

But in the movie, as in the play, we eventually arrive at the end, perplexed. It is the last scene, and—I won’t go into the “how” of it, but suffice it to say Lucentio and Bianca have saved the day. The women, including Kate, gather in a celebratory mood and move off stage together. At this moment Petruchio roundly and smugly offers a wager to the men.

BAPTISTA

Now, in good sadness, son Petruchio,

I think thou hast the veriest shrew of them all.

PETRUCHIO

Well, I say no. And therefore for assurance

Let’s each one send unto his wife;

And he whose wife is most obedient

To come at first when he doth send for her

Shall win the wager …

Suspense ensues, but it is, in the end, Kate who fully obeys. And not only does she cap the wager, she fully castigates any and all women who don’t—obey, that is—she implores us all:

KATHARINA

Thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper,

Thy head, thy sovereign

. . .

Come, come, you froward and unable worms!

My mind hath been as big as one of yours,

My heart as great, my reason haply more,

To bandy word for word and frown for frown;

But I see now our lances are but straws

. . .

And place your hands below your husband’s foot,

in token of which duty, if he please,

My hand is ready; may it do him ease

Well then, what brought this on? Was our playwright compelled by law? Forced to stay within the lines of official decorum while still cramming his verse with every saucy-natured double entendre imaginable? (It was not just Christopher Marlowe, by the way, who found himself plunked into the London gaols for not obeying the censors).

Well, whatever. It is what it is. Time goes on.

And our movie? Not as popular now. That was ’67. Soon came ’68. Soon college women were marching in solidarity. Raising fists, throwing off the shackles. Needless to add, their tolerance for any contemporary representations of shrew-taming was done and over with.

Lucky for us, Shakespeare himself got another shot at popular acclaim when Franco Zeffirelli followed his “Shrew” with one of the most successful pictures ever made, “Romeo and Juliet” (1968).

New American Shakespeare Tavern “Taming of the Shrew” (2017)

We now fast froward … to today.

New American Shakespeare Tavern

Think of our humble Tavern as a window into the past. We sit at pub tables on stage level, other patrons drifting into the balcony overhead, and we gaze out at the Elizabethan world before us. It is all stone and wood and set with arched doorways and tapestry-like curtains and stately columns and one overhanging balcony. We mute our phones. We swill our beverages. Some finish off their Shepherd Pies.

Lights dim. Actors emerge from the shadows. The characters grab our imaginations, and hold forth in strange tongue which somehow seems not so foreign after a time. Lucentio and Hortensio and Baptista and their servants make merry as they flaunt their colorful raiments, now from the stage of the very Globe itself.

Petruchio in this light is not mean, not petulant. He is determined. He is passionate. He commands the action, clearly knows his mission, but he possesses a clutch of human frailties as well. In one monologue he holds a lone candle, casting an eye to the night, querying the spirits with questions he cannot answer.

His Kate is real to him, and so to us. Her glare is pure ice, her venom stinging, but her hunger is palpable too, as is her desire to be taken seriously, on her own terms, her oh-so-human aching for independence.

Once fully steeped in these machinations, political incorrectness seems far in the distance. So it is that “Shrew” as well as “The Merchant of Venice” (1599)—their texts somewhat shaken by the political realities of the 19th and 20th centuries—still shine in performance. It is the characters, not their type, not their trajectories. Yes, even in those plays where archetypes come dangerously close to stereotypes, we become not only viewers and listeners, but empathizers as well.

Brash Hollywood in its infancy

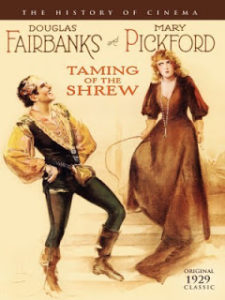

Well, not all of us. Over the years there have been attempts to make the shrew less shrewish, her submission less submissive, and the character of Petruchio less overbearing. Among them is the “Shrew” talkie of 1929, starring Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, which featured the infamous “wink” that Pickford-as-Kate makes to Bianca during her final speech.

An adaptation begets a movie

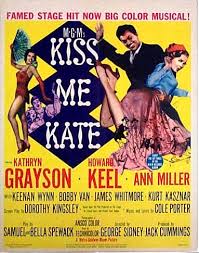

There is the upbeat and much-beloved Broadway adaptation (and play-within-a-play) “Kiss Me, Kate” (1948) with some of the best songwriting that Cole Porter ever penned. There was a BBC production (1980) starring John Cleese as Petruchio (yeah … you get the picture). And there was John R. Briggs’ “Shrew: The Musical” (1993) a modern-era, tap dancing send-up set upon a soiree in Palm Beach—one of those “loosely based-on” things. Of the latter, Atlanta’s “Creative Loafing” theater critic Denia Moreland remarked: “There’s nothing worse than a nagging woman; a singing, dancing nagging woman, however, might just be worthwhile.”

Meryl Streep as Kate (1978)

Every director, actress and actor has to come to terms with this play. Meryl Streep played Kate in the Shakespeare in the Park production in 1978 and famously remarked it was “Love” that lifted the play. In the 1967 movie, Elizabeth Taylor turns and flees at the end, making Petruchio follow her out.

There was blowback even in the heyday: playwright John Fletcher’s “The Woman’s Prize, or The Tamer Tamed” (1616) brought Petruchio back to the stage as an aging widower, and his late-life wife Maria (yet another shrew!) ladles up a goodly dose of his own medicine. David Garrick’s adaptation “Catherine and Petruchio” (1754), popular for more than a century, seems purposely to have salved some of the bite from the Elizabethan production, and endured for the many years that “Taming” was put on the shelf. When the Shakespeare version was eventually revived in the late 19th century, snubs followed also, most notably from “Pygmalion” creator George Bernard Shaw, who was embarrassed by the final monologue of “Taming” and humorlessly labelled it “one vile insult to womanhood and manhood from the first word to the last.”

The Selling of the Shrew

In our time, it goes without saying that each artistic director applies his/her own tweaks for how to sell Shakespeare’s most controversial play to a modern audience. The clever stuff is simply not enough. As mentioned above, this century’s prior efforts have been to alter Kate’s reactions, or to tailor the inflection of one of her phrases or another, or perhaps even restyle her body language in ways that establish and reinforce her valiant self-respect. It is, in fact, a re-framing.

Matt Nichie and Dani Herd

And while Dani Herd’s Kate was winning and stalwart, and she played it with all the flux of her strong emotions—anxiously convincing, powerfully modern, unapologetic—she does not, in the end, pull a wink-wink. She manages quite well to hold on to her stubborn self-confidence, a seeming necessity these days, even as she offers her Kate into the waiting arms of Petruchio.

So would we in the 21st century now have Petruchio take the hit? In Matt Nichie’s performance, his Petruchio does seem to soften the blow. He is twinkle-eyed and cocksure, a bit deranged now and then, still hungry for domination, true. But somehow in all that fulminating and grousing around, it is Petruchio himself who sprinkles in Meryl Streep’s required ingredient: love. And oddly, it works. Nichie’s sly, sometimes intoxicating gestures toward Kate evoke a tenderness from him all throughout the play. That, quite frankly, is not in the text.

So it is that “Taming” thunders on, still prodding our thespians to cobble an ingenious turn or a subtle performance to take the edge off the misogyny. The woman must be given her due these days. We require that—especially if, at the end, a long, loving kiss be made to seem possible—perhaps even believable.

2 Responses to “The Re-Framing of the Shrew”

Dare I say, this play is genius because of its intended ambiguity. Shakespeare gives the characters actions, words, and leaves the intentions entirely up to the director/actor. Almost daring us to claim we know what he meant by it.

Agreed. Shakespeare leaves the door open far more than most other playwrights. But I believe my point is that we have reached a crossroads with this particular play where directors have no other choice than to adapt if they want to appeal to a contemporary audience. The stark meaning of the words is so utterly intransigent; that leaves only performance tweaks.