Shakespeare’s Wife

’Twas the last week of November in the year 1582 when William Shakespeare, who was at that time not even close to becoming a Bard, married a woman somewhat older than he. She was one of the Hathaways, a local farm girl. Her name was Anne, and she was a blushing twenty-six. William, as has often been said, was “only” eighteen. A daughter, Susanna, was christened six months after the wedding.

John Shakespeare’s House on Henley Street

The match took root in and around the small market town of Stratford-upon-Avon where William grew up, located a hundred miles north of London. On how their romance flourished, how long it went on, whether it was years in the making, or weeks or months, whether happy or sad or scandalously shameful, we have no information.

As for William, he was the first of his parents’ six children. We know a smidgeon about the lineage of his mother, Mary née Arden, based on her family tree. Thanks to court records we know a little more of William’s father, John Shakespeare. John was one of two “glovers” in Stratford but seemed always to be hemorrhaging money. He worked from his two-story family house on Henley Street, and in the year William was born, he was a respectable civic leader. But by the time of the wedding, a scurrilous and chastened John had fallen deeply into debt and out of favor with his fellow citizens.

The Hathaway house on Hewland’s Farm, now known as Anne Hathaway’s Cottage.

As for Anne, she was a farm girl from Shottery, a village within easy walking distance of Stratford. She had a younger brother, Bartholomew, who would one day become a respected farmer. Her mother had passed away when she was a child. Her father Richard had remarried, but alas, he died just a year before the wedding. After the wedding, it is assumed the newly married couple moved in with John Shakespeare’s family on Henley Street. Anne’s stepmother Joan continued to live in the farmhouse with her family. Both homes are still standing. The farmhouse is now called Anne Hathaway’s Cottage.

Of William and Anne

At a personal level, these two remain the most mysterious couple in the world of sixteenth century celebrities. The reason? We have almost no intimate information about them: no diaries, no log of William’s comings and goings, no references to any of Anne’s activities, no letters between them, no letters to or from anyone else, no famous lines written on the backs of receipts. There are achingly few mentions by their contemporaries, critics, other playwrights, friends or relatives.

It is likely Anne had no formal education, which was the case with most young women during this era, and she may or may not have learned to read. Most scholars believe that William completed his education—that is to say, “grammar school”—at the age of fourteen. We know from his poetry and plays that he was certainly acquainted with the stories of the Bible and the poetry of the classics, especially the Roman author Ovid. But after leaving school, we don’t know anything about what he was doing for a living. There are a number of theories, as you can imagine. As for the arts, he may well have been inclined to entertainments in the form of traveling minstrels and touring theater ensembles. But of William’s interest in such things, we really have no solid information.

Imagine, for a moment, that you are a Shakespeare historian. In trying to paint a believable portrait of the living experience, you have no choice but to connect your documentary factoids to subjective conclusions. No matter what you say, even your closest colleagues will ardently disagree with you. Some of your hunches will be called fanciful, others fascinating but unfounded, a few brilliant. But your fellow researchers have their own higgledy-piggledy methodologies, resulting in a state of confusion for readers in search of truth. This is how Shakespeare biographies now appear to us: like so many intricate guessing games.

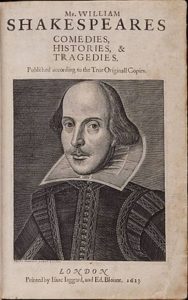

The “First Folio” – 1623

There is one likeness that can be definitively dated to within the years of their lives—the portrait of William on the “First Folio” of his plays, published seven years after his death. Most experts deem it to be accurate. A few others might be based on contemporary sketches, but in general the images we have of them are believed to be painted or sketched or engraved much later.

Of course we have William’s plays and poems to pore over. Of his 154 sonnets, there is but one that experts think is devoted to Anne. Most other documents, legal filings or official business transactions, do not mention William’s wife. Over the last two to three hundred years, researchers have been hard pressed to turn up anything in the way of significant biographical discoveries within the couple’s lifetime. The substance of William and Anne’s private lives persist in a netherworld.

Of Their Family

Following the birth of their first child Susanna, records show that Anne gave birth a second time, in 1585, to twins—a girl, Judith, and a boy, Hamnet. Hamnet seems to have been named after Hamlet Sadler, a friend of William’s. The two name variants (Hamnet/Hamlet) were in those days what linguists now call “phonetic equivalents,” which is to say, each name was legally and conventionally interchangeable. As for spelling, there were no rules—I am sure many of you have seen the surname Shakespeare spelled any number of ways in the script of the day. Then there is Anne. She herself is known to have three name variants: Anne, Ann and Agnes (this last pronounced “ANN-yiss,” as in the French). She went by all of them.

The early years of William’s and Anne’s marriage are beset by the doubts and questions of scholars. Had they actually been in love, or had they just been feeling frisky? If the latter, had Anne tricked William into this union, or vice versa? With whom did they live during the first months and beyond? What lay in the interval between the birth of their first daughter and the birth of their twins?

“The Farewell” – Anne is holding Judith, Susanna at her heels. Will is giving Hamnet one last hug before heading off to London.

And what to make of the “the lost years”—the utterly undocumented period between 1585 and 1592? Was Anne supportive of William’s desire to move to London, or was she determined to stake him to Stratford? How fared those first years of their long-distance marriage? How might William have managed to learn both acting and playwriting in such a short period of time? And later: was it a mutual decision to live apart most of each year?

All is speculation—that is, until we learn that William was regularly writing and acting for London playhouses around 1592.

Of the London Scene

’Twas the heyday of Elizabethan theater when William left Stratford for London sometime during the lost years. The scene was indeed a rare opportunity for an aspiring actor and writer. In the public sphere, plays were the thing. Actors and writers were in high demand. And while the English novel hadn’t yet been invented, books had been around a long time. Histories, epics, and entertaining book-length poems were very much in fashion.

For playwrights, though, theater was a gig economy. Most were paid by the piece, and as a result many such scribblers were chronically broke, some more than others. But talent could also be richly rewarded. The names of William’s prestigious contemporaries are still well recognized: Christopher Marlow, Thomas Kyd, Beaumont and Fletcher, Francis Bacon, the illustrious Ben Jonson. Within his first few years William is believed to have contributed to several playscripts. Not long afterwards he himself had a few decent plays under his belt, and eventually he became quite well known for his unique and clever way with words. He even had his critics. He was also writing sonnets in his leisure time and wrote book-length narrative poems of a classical nature. His big break in the theater came in 1594 when he signed on as shareholder in a major new company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. William must have worked night and day and saved every penny, for by the year 1596 we know that he was doing quite well for himself.

Of Their Home in Stratford

But 1596 was also a tragic year for Anne and William. Their son Hamnet died at the age of eleven. The cause is unknown—infection, birth defect, accident—any and all are up for grabs. The latest variant of the plague might also have been the reaper, but even so, questions rain down. Was Hamnet’s death sudden or expected? Was William able to comfort Anne, or even return to Stratford in time for the funeral? Surely a message would have been sent, perhaps by courier, but missives could take days to arrive in London. (His trip home would have been, at minimum, a two-day affair.) Again, we know nothing.

Following these events, the verifiable facts of Anne’s life recede into the woodwork at about the same moment in time when William acquired serious name recognition. We know some things about his finances, and in 1597 he was doing so well for himself that he purchased a spacious home in Stratford called New Place. Anne and her two daughters moved in, and some of the rooms were rented out. Eventually, William even rented out his father’s old house on Henley Street.

To us, it would seem likely that William would have returned to Stratford whenever possible, during plague years, say, or possibly during the touring season. But alas, there is no indubitable evidence of that. We only know for sure that William returned to Stratford in the last years of his life. As if to mirror the fog of his possible visits home, there is also no evidence that Anne herself ever made it to London.

William regales his family with stories on a trip home; Anne sits on the right, Hamnet is standing, the girls leaning in. German engraving, 19th century.

We can certainly imagine otherwise (and scholars do): the occasional visit by William, Anne’s raising of two daughters and running multiple households in the 32-room virtual hotel of New Place, keeping up with the in-laws, friends, extended family, and renters. We know for a fact that their first daughter Susanna married quite well. We know their second daughter Judith married not so well. And we know a little something of their grandchildren. But we have no contemporary or primary evidence or anecdotes about Anne herself as a housekeeper, gardener, mother, mother-in-law, older woman or widow.

For centuries, scholars have burned the midnight oil reading between the lines of the plays, unearthing documents, court records, wills, family ties and community news to fill out the picture. But as for their personal lives, little of substance has passed the test of time. Anne’s verifiable life and contribution is as bare as a poor man’s cupboard.

Of Their Last Years

Early into the new century, we know William was still writing, and chiseling away at his most monumental tragedies: Hamlet, Lear, Macbeth, Othello. He seems to have given up acting in the middle of that decade. At this time he was also engaged in some business and property transactions, mostly around Stratford, and we know a little bit about those. We know he eventually retired, possibly part-time at first, then full-time around 1613 when he settled into New Place, once and for all, and gave up writing plays. He died at home in 1616 at the age of 52.

A curious enigma hovers over William’s last days. In his will, William left only his “second-best bed” to his wife Anne—a hard nut that has cracked many a scholar’s tooth. Nonetheless most historians agree that (1) Anne, by law, would also receive one-third of his primary property holdings, (2) daughter Judith received a small behest of money, and (3) Susanna, his eldest daughter, then married, received the lion’s share of the estate and other holdings, indeed virtually all the remaining properties.

Anne died in 1623 at the age of 67. We ponder the meagre leavings of two puzzling lives that we would like to believe were, at least now and then, privately rewarding and well-lived—but no one knows. Lest you think there might be significant evidence soon to be revealed, allow me to assure you there is none. A powerhouse industry of imaginative supposition made up of plays and films and novels, even loopy scholarship, is the result.

Of Their Afterlives

Afterlives are the last best arrows in the historian’s quiver. While this odd concept was new to me, the term is well-worn in the halls of academia. Today it is used to bundle any newly discovered tidbits, possible or imagined events, and even unlikely rumors into the anecdotal/biographical post-life of well-known persons. It contains what readers over the centuries believe about them, and is culled from sources such as novels, plays, histories, and all manner of gossip and innuendo.

Thus the curtain has never come down on the possible lives of William and Anne. Together or apart, they sally forth in play after play, novel after novel, history after history, determined to make the best of things back in their day. In this way, our two obscure if famous people do indeed live on in the scribblings of writers, scholars, playwrights, your Google newsfeed, and yes, even in the dark and smarmy alleys of conspiracy theorists. But be forewarned: if the evidence seems too good to be true, let be it known that every new surmisal is hotly disputed.

William’s afterlife began its resurrection seven years after his death. That was when two of his close friends compiled thirty-six of his plays, eighteen for the first time, into the “First Folio,” published in 1623. Then, twenty-five years later, his afterlife was cut off at the knees: a prohibition on public theaters was imposed by the English Revolution of 1649 and lasted two long decades. Following the blackout, however, William’s reputation came back to life—in fact, it launched a bit of a rebirth for him. By the eighteenth century William’s plays were hailed as genius, even on the continent. By the nineteenth, he had morphed into the national poet of England.

But what of Anne’s afterlife? We’ll get to that, after a word from our sponsor.

Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard

“Shakespeare in Love” (1998)

This award-winning movie—cleverly concocted by Marc Norman and whipped into an outrageous soufflé by the inimitable playwright Tom Stoppard—has become the gold standard of pure Hollywood poppycock. (It is also, I confess, one of my favorite tours de force.) If you have seen it, you will know the person of Anne is not even in this movie. But since she is alluded to, for now we’ll just say she’s an important footnote.

This award-winning movie—cleverly concocted by Marc Norman and whipped into an outrageous soufflé by the inimitable playwright Tom Stoppard—has become the gold standard of pure Hollywood poppycock. (It is also, I confess, one of my favorite tours de force.) If you have seen it, you will know the person of Anne is not even in this movie. But since she is alluded to, for now we’ll just say she’s an important footnote.

Near the outset, we find a desperate Will racing through the narrow, crowded streets of London, leaping up a staircase to a back-entrance landing, then bursting through an outer door to a shadowy inner sanctum. It is the residence of one “Dr. Moth, Apothecary,” who is revealed to be in the act of shagging his assistant secretary and aspiring actress, Rosaline.

Will instantly takes to the couch and gives himself up for analysis. Moth sighs and shakes himself loose.

WILL [lying on the sofa] I have lost my gift. It’s as if my quill is broken. As if the organ of my imagination has dried up. As if the proud tower of my genius has collapsed. … Nothing comes. It’s like trying to pick a lock with a red herring.

DR MOTH Tell me, are you lately humbled in the act of love? … You have a wife, children?

DR MOTH Tell me, are you lately humbled in the act of love? … You have a wife, children?

WILL I was a lad of eighteen. Anne Hathaway was a woman as old, and half again.

DR MOTH A woman of property?

WILL She had a cottage. One day she was three months gone with child, so …

DR MOTH … and your marriage bed?

WILL Four years and a hundred miles away in Stratford. A cold bed too since the twins were born. Banishment was a blessing.

DR MOTH And now? Are you free to love?

WILL Yet cannot love, nor write it.

[Here Dr. Moth rifles through a crystalline bowl of baubles and bangles and pulls out a glittering “snake bracelet”]

DR MOTH The woman who wears the snake will dream of you, and your gift will return. Words will flow like a river. … I will see you in a week.

And so it would seem the mystery of Shakespeare’s marriage is no mystery at all. All has been revealed here by the young Will who has accused his long-distance wife of being a shrew. For not only was he coerced into wedlock by this scheming Anne, but some years earlier he had been banished altogether from his family in Stratford.

Believe this? Sadly, many do even today.

Bardolatry

The English, you see, are very well aware of what’s going on here. The movie’s reference to cradle-robbing by a shrewish and illiterate Anne is a standard feature of Shakespeare worship, a curious mindset most often referred to as bardolatry. And it is the master key to unlocking the mystery of Anne Hathaway’s curiously miserable afterlife.

David Garrick embraces a bust of the Bard

Bardolatry can be traced back to 1769 when the stage actor David Garrick conceived and produced the world’s first Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford. In a bit of doggerel made up for the occasion, Garrick declared Shakespeare “the god of our idolatry” and “our matchless Bard.” Garrick refused to even acknowledge Anne—oh she of low birth, so unworthy of our Bard—and forbade her name to be used in any of the activities or bills publicly posted.

Garrick had his followers. His notion of an ideal Shakespeare was dangerously close to godlike (think Michelangelo), and the obsession morphed ever so gradually into a near religion in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. So while Garrick may have been the first openly worshipping bardolater, many have since donned the mantle.

Not all, by any means. George Bernard Shaw, who popularized the name “bardolatry,” had nothing but sneering insults for intellectuals who literally worshipped the ground Shakespeare walked on. But over time, as odd as it sounds, even eminent authors like James Joyce and Anthony Burgess kept the flame alive and continued to hold Anne personally responsible for William’s leaving his family. Anne, you see, was the nagging wench that forced Shakespeare’s hand, which in turn justified William’s leaving not just her but his entire family behind in Stratford, for the fabled and superior life he was about to lead.

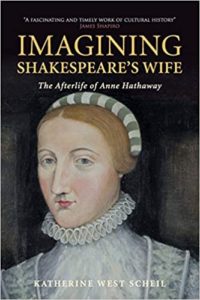

Katherine Scheil

“Imagining Shakespeare’s Wife” (2018)

Though the particulars of Anne’s life are few, it turns out she has had many afterlives. In this book, Katherine Scheil, a professor of English at the University of Minnesota and Director of the Citizen Shakespeare Project, seeks to explore every possible appearance of Anne in a leisurely stroll through the last four centuries of quaint, often scandalous, and sometimes even rather trendy Annes—which is to say, a mostly delectable stew of reinterpretations.

Though the particulars of Anne’s life are few, it turns out she has had many afterlives. In this book, Katherine Scheil, a professor of English at the University of Minnesota and Director of the Citizen Shakespeare Project, seeks to explore every possible appearance of Anne in a leisurely stroll through the last four centuries of quaint, often scandalous, and sometimes even rather trendy Annes—which is to say, a mostly delectable stew of reinterpretations.

In the Elizabethan era, we know that by the time unmarried British women had attained the advanced age of twenty-six, many would have already left the nest. Typically the women of that world “went into service” in other, more affluent homes where they could expect to receive room and board for their base pay in addition to extra earnings. But Anne also had a dowry willed to her by her father and payable upon her betrothal. So perhaps she was still hanging around Shottery, making a life for herself, and hoping. Though propertyless, she would at least not be seen as penniless to a new suitor.

Katherine Scheil

Anne might have helped out in the fields, and in that capacity she may have been allotted some land for crops or gardening, and she could possibly have been contributing to household maintenance: growing herbs, say, caring for animals, tending fields of malt. Furthermore, she may have been presenting herself as quite available when William likely came a-courtin’.

All this, to illustrate how the use of modal adverbs has become required syntax for the way Shakespeare scholars must write about their subjects. Which is to say sung with a certain gusto, but liberally hung with contingencies.

Afterlife 1

The Goody-Two-Shoes Anne

Back in the world of the Jubilee, in 1769, the descendants of the Hathaway clan were gearing up for their own slice of the pork pie, hauling in any tourist with a pocketbook and the expectation to be immersed in the special world of William and his wife. As the English countryside around the backwater of Stratford flowered into a destination, so too an upsurge in tourism coincided with new trends of curiosity about the private lives of writers.

“Shakespeareana”—physical objects in the form of relics, stories, furniture and the like—were added to the aura of the Cottage to create a tangible, physical memorial to the ideal of romantic love, and project imaginary relationships. By the late eighteenth century, our humble Anne had become an icon of Elizabethan womanhood. Storytellers and biographers got in on the action, romanticizing the farmhouse association with both Anne and William. There were travel guides, novels and children’s books, all of which helped to advertise the unique “experience” of the Cottage, which would gradually morph into a nineteenth century symbol of pastoral bliss: an inkstand here, a pair of gloves there, a courting chair, a bugle purse, books and illustrated postcards—all brought to life by guides who walked visitors through the kitchen galley, the living rooms, bedrooms and gardens, filling in the everyday details behind the lives of the Shakespeares, about whom we know almost nothing.

Mary Baker

Mary Baker—a Hathaway family descendent and true “spirit guide”—

outfitted herself in frock and apron and was a veritable font of spritely legends and imagined scenes spilling endlessly over and over for the paying multitudes. Lest skeptics cast a doubtful eye, the Hathaway family tree was featured on the end pages of the original family Bible shown here lying on the table beside her.

Illustration from ”Will Shakespeare’s Little Lad”

A look at the names of pilgrims signing the guest book reveals some oddly fawning luminaries such as Charles Dickens and General Ulysses S. Grant. You could buy stuff for the kids. There was “The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines” (1850), and Imogen Clark’s “Will Shakespeare’s Little Lad” (1897), that featured the childhood adventures of Hamnet. Among the many adult novels was Emma Severn’s “Anne Hathaway, or Shakespeare in Love” (1845), featuring William himself as a modern Romantic hero who gets his literary inspiration from Anne and her Cottage.

In Scheil’s telling, these offerings were intended to project a family man who could “discern with sympathy the innermost core of woman’s heart.”

Afterlife 2

The Artful, Independent Anne

In 1870, a piece ran in Gentleman’s Magazine entitled “The True Story of Mrs. Shakespeare’s Life”—a delightful little horror story which was more than likely ghostwritten by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Here we have Anne dwelling in retirement in her lonely country house with nothing to do. So to add a little spice to her life, she becomes an accomplice to the murdering deeds of William, who has taken to luring rival playwrights to his isolated Warwickshire home, whereupon he kills them and buries their bodies under a mulberry tree. Yes, all in an effort to do away with his competition.

A new independent-minded Anne begins to appear in the Belle Epoch of the late nineteenth century. It is a time when all manner of secret enticements and ill-gotten manners were on the table for readers of the popular novel, many of them written by women.

There was “Shakespeare’s Sweetheart” (1905), promoted as “lavishly illustrated,” and targeted for a new audience of the fin de siècle, also featuring a same-sex partner for Anne. There was Anna McMahan’s “Shakespeare’s Love Story” (1909), which imagines a literate Anne who not only inspires her hubby’s sonnets but becomes the inspiration for his many plays.

And then there was Mabel Moran’s surreal one-act play “The Shakespeare Garden Club” (1916), where Anne puts on a posh garden party with all her husband’s most glamorous female characters (Lady Macbeth, Portia, Jessica, Titania, Ophelia, Juliet and Mistress Ford). At the gathering, the ladies concoct a plan to undertake a tasteful landscaping project near the river Avon. One can only guess the riverside had become something of an eyesore.

Afterlife 3

The Mad, Evil, Underclass Anne

From the beginning of William’s afterlife, about him always swirled rumors. Dalliances! A womanizer! He cavorted with prostitutes. He had affairs with this or that female, such as the landlady at the Crown Inn, or one “Mrs. Davenant” in his old haunt in the Warwickshire countryside. (From this last he supposedly had a bastard son.)

Again, not one of these many claims has ever been proven. That said, the upshot is that this particular William is a prototype we shall call the “libertine Shakespeare,” the man who was chased out of Stratford by the “Evil Anne,” his very own wife, a banshee of a woman he was tricked into marrying. Translated into scholar-ese:

There is a marked tendency, especially among the more imaginative writers upon Shakespeare’s life, to represent Anne as a yokel daughter of a peasant father, and the marriage a mésalliance for the son of a prominent Stratford burgess.

—C.J. Sisson “Shakespeare’s Friends” – an article first published in the journal “Shakespeare Survey” (1959)

The decrepit Anne, as Anthony Burgess will eventually call her, was engineered in part by the bardolaters themselves, who would have us believe that Anne tricked a teenage William into having sex, the result being a shotgun wedding.

The March of the Bardolaters

Malone, Brandes, Joyce

In 1798, a writer named Edmond Malone was having none of Anne’s recent beatification. Malone was one of the very first serious scholar/bardolaters and something of a renegade as well. In his unfinished biography of Shakespeare, Malone went full-bore:

[William Shakespeare] appears … to have written more immediately from the heart on the subject of jealousy … and it is therefore not improbable he might have felt it. … Jealousy is the principal thing of four of his plays. He might not have loved Anne, and perhaps she might not have deserved his affection.

Edmund Malone

Malone seems to have been the first to systematically employ the technique of preselecting certain plays, and certain characters from the plays, to shed light on the personal life of his Bard. Malone was the also first among many to use the age difference against Anne, and from there proceed to build a case that William himself must have felt tricked, perhaps even henpecked, and, following the wedding, eternally trapped. Their love affair, if indeed it could be called that, ended in what Malone imagined to be a disastrous marriage. Remember that bequest in William’s will—the one to Anne of William’s “second best bed”? Well, that was due, Malone said, to Shakespeare’s jealousy at Anne’s own overweening infidelities.

If you don’t buy into the bardolatry, Malone’s arguments are a crazy quilt of criticism intended to leave Anne’s popular image, her family and her children, at the doorstep. Malone’s method is to associate characters in the plays with moments in the life of the Bard. Each of William’s arch and controlling women becomes a suitable stand-in for William’s similarly scheming wife back home in Stratford. Malone substantiates his points by quoting lines from the plays themselves and inferring from the judgments of the characters that William felt the same for his own wife.

Not what you’d call proof. But while airily superficial, this line of attack had the appearance of scholarship, even though it seems to have been a minority viewpoint in the late eighteenth century. Eventually, though, the anti-Anne sentiment grew beyond critics and was sifted into novels and popular histories of the day. Historian Richard Grant White wrote about Anne in his popular “Memoirs of the Life of William Shakespeare” (1865), calling her a “predatory older woman.” White even openly wishes she had died rather than marry Shakespeare.

Georg Brandes

It was only a matter of time for more serious scholars to take notice of this unworthy Anne. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Georg Brandes, a critic from Denmark, resurrected Malone’s thesis, and managed more efficiently to nail down the logic in many of his arguments. His book “William Shakespeare: A Critical Study” (1895) made the claim that Anne, William’s “peasant girl,” could never “fill his life.” Brandes could only imagine a passionate spirit in William that he did not see in the match with Anne. He wrote that William was meant to be living “the free Bohemian life of an actor and playwright” in London. Brandes proceeds to weave this idea through a study of each of the plays.

Wandering in the desert of fact, many a modern scholar were at least intrigued. Brandes’ research was favorably reviewed. Soon there was another bardolater in the hunt, the journalist and critic Frank Harris, whose book “The Man Shakespeare and his Tragic Life Story” (1909) fully fleshes out the sad tale for the public at large. Harris tells of a despairing Shakespeare bolting for London to escape an unhappy marriage and diving into a passionate affair with one Mary Fitton, perhaps his “Dark Lady.” Scheil notes:

For Harris, Shakespeare was a man of “excessive sensuality” and “mad passion” that could only be assuaged by an extreme, libidinous lifestyle.

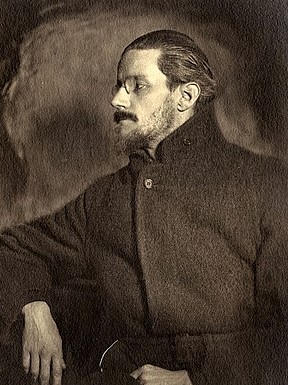

James Joyce

Within a decade Brandes’ book became highly influential among intellectuals and historians. In particular there was a rising literary star, one James Joyce, who as a young man read Brandes’ book and later turned those themes into literature. In “Ulysses” (1922), Joyce’s narrator Stephen Dedalus cuts loose on Anne Hathaway’s purportedly uncontrolled lust and her own assorted dalliances. (We must remember Joyce’s world was not so much history as myth-history). Anyway, while Joyce himself might not have been taking Anne all that seriously, some literary historians saw for themselves a new line of attack. Many did read “Ulysses,” and many did take it seriously.

In Scheil’s telling, Joyce trots out what are now considered tired old clichés and consolidates them into one big confection of ridiculous passion. In the following summary Scheil gathers Joyce’s choicest diatribes as the writer pursues the “entrapment narrative.”

Anne in Ulysses is “hot in the blood,” “the ugliest doxy in all Warwickshire,” and “a boldfaced Stratford wench who tumbles in a cornfield a lover younger than herself.” Sexually aggressive, she “put the come hither on him,” Shakespeare “made a mistake,” and he “got out of it as quickly and as best he could.”

Joyce even goes after Anne later in her life, as an aging crone who was desperate to get herself a man, any man. Here Scheil quotes Joyce’s text, in a passage describing an almost pathetically decrepit Anne:

A slack, dishonored body that was once comely, once as sweet as cinnamon, now her leaves falling, all bare, frighted of the narrow grave and unforgiven.

This “wretched-Anne” stuff is, of course, a minor thread in a much, much larger tapestry that Joyce is weaving. But as the depiction spread into popular literature, other novelists took their own swings. There were even West End and Broadway plays in which Anne suffers the slings and arrows of outrageous bardolatry, and eventually there was some part of the jeering public that glommed onto a mad Anne Shakespeare. One such minor league effort was Charles Edward Lawrence’s “The Hour of Prospero” (1927), a play in which Anne devolves into a psychic mess. As summarized by Scheil, Anne’s expression on stage is “vacuous,” “a picture of worn-out womanhood.” Anne believes her husband, “wasted his years over trash,” writing poetry of all things. It was not William who grieved; it she herself who suffered alone. Anne laments “working my fingers to the bone” … and, well, the monolog goes on and on. In the end she simply collapses into “delusional muttering.”

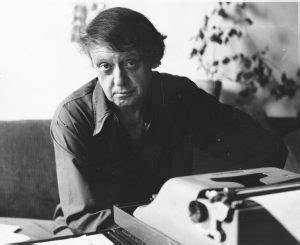

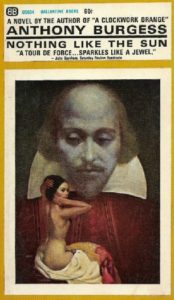

Anthony Burgess “Nothing Like the Sun” (1964)

Among all the authors, contrarians, and television intellectuals of the Sixties, there was this shaggy-haired English novelist and bookish bad boy, Anthony Burgess.

Anthony Burgess

Burgess’ schtick was a sort of shock-and-awe version of the anti-establishment libertine. He performed it well. But while publicly itching for a fight on TV, he actually made a decent name for himself pumping out books, novels, biographies, articles, screenplays—even classical music(!)—in prodigious numbers. Best known for his early novel “A Clockwork Orange” (1962), featuring an insanely violent gang leader Alex, accompanied by his “droog” gang members, Burgess invented for them a street slang all their own. Eventually the book became a bestseller, and a blockbuster movie followed, each of them equal parts dystopian and satanic.

Two years later, Burgess turned his attention to the early adult life of William Shakespeare in a novel, “Nothing Like the Sun.” The author imagines a Shakespeare who was, yes, a genius, but a bit of a bloke on top of it all. He is known as “WS” in the novel, which also employs a narrative language that is intentionally proto-modernistic, and also devises a street slang stitched together from both Elizabethan and modern English.

The title is lifted from the opening line of Sonnet 130—“My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun”—an early poem that was written in William’s youth, a sonnet that quite literally evokes the fatal attraction of a mistress, a woman possibly of African descent. Burgess was no scholar, but he knew his Shakespeare, and he knew bawdy, and in this novel the Joycean “entrapment narrative” is most fully fleshed out.

If you read it, you will never forget the famous scene. One gorgeous evening on the May Day celebration of 1582, WS is walking about the parade grounds with friends when Anne Hathaway spots him. WS returns her glance. Anne is on the arm of another chap but smiles and waves hello. Later that evening WS gets roaring drunk with his fellows, and much later that night, having had far too much to drink and losing consciousness, he awakes groggily on the fields and in the arms of this same Anne, whom he scarcely knew, this Anne somebody—who was she again? The night was pitch black. And where were they? Under a tree? Had they, in his drunken state, perchance kissed?

It is all a blur. In his delirium and under the stars, WS realizes this girl is no girl at all—at least not young—“she was no plum-plump pudding of the henyard”—she was a woman, of all things. In fact, a maneater. She grips him in her arms and makes passionate love to him, and he is wholly devoured by her indelicate carnal knowledge. In their heat “she gripped him with powerful talons and let forth a pack of words he had thought no woman could know.” It is a moment of love that hits WS as simultaneously both shocking and sinfully delicious.

Within a month Anne finds herself quick with child. WS makes all kinds of denials and excuses. He tries to wriggle out of the marriage by proposing to another Anne in his life, one “Anne Whateley” (known well to scholars and also listed on the marriage register), who honorably declines—and in the end WS is forced into wedlock by a team comprised of his parents, Anne’s brother, and two farmhands who have been sent to track him for fear of escape. Out of options, WS consents to wed.

Post-wedding, he and Anne move in with WS’s parents, their outward homelife appearing humdrum. But in the confines of their bedroom Anne becomes a banshee. Away from his parents, he never knew what she might do. She might pretend to be a boy, or, acting out, she might become a Queen demanding subservience. WS was shocked to find she had a dildo in her chest of drawers.

He disrobed her in great difficulty, for she scratched and fought, and he was fain to desist from such fatiguing play.

So why is this rather odd book still in print? People love it, that’s why. The story is uniquely raunchy, and that erotic cover illustration still sells. It’s a pity that Burgess went with all the wench stuff, but that was indeed his author’s calling card. In the details, Anne is not a real person—perhaps less an archetype than Joyce’s, perhaps simply more of a plain-Jane trollop than a worthy wife.

In the book her “acting out” goes on and on, nonstop. As their marriage bed devolves into a rotating merry-go-round of sexual gameplaying, Anne’s insatiable lust plays a significant role in forcing WS to seek a more refined and sensuous life. For Burgess and Joyce and rest of the bardolaters, you see, Anne was far too old, far too low class, and, updated here in Burgess’ telling, far too sexually crazed.

So it is that WS soon becomes enthralled with other more, shall we say, sophisticated women. In this novel, our burgeoning poet begins several taste-tests of his own, for he too has now discovered the hunger. It doesn’t take long for Burgess to push Anne out of the way and make room for a beautiful dark-skinned woman who we take to be the “Dark Lady” of the sonnets (a favorite Shakespeare trivia game answer). There are others that Will finds, of course, especially in London, among them a man, the impossibly-spelled Henry Wriothesley (pronounced “REZ–ly”), the 3rd Earl of Southampton and who was, as some have proposed, William’s gay lover.

WS’s nascent talent is never limited by a mere codpiece. He is a bit of a stud genius whose mind is always roaming. From this point on, Anne, and presumably her three children, pretty much vanish from William’s far more important sex life. As summed up back then by the book critic for the New York Times:

[Shakespeare’s] topless towers of words were founded on his immense desire and will [as part of his] “phallic power.”

Stephen Greenblatt

“Will in the World” (2004)

Just when you’d think bardolatry had passed its sell-by date, in our world there is yet another incarnation that must be revealed.

- As a highly regarded scholar at Harvard, Stephen Greenblatt is the author of many books, and also the originating proponent of a movement called New Historicism.

- As a throwback to a strangely fictional underworld, Greenblatt is as convinced as any card-carrying bardolater that Shakespeare was screwed over bigtime by his shrew of a wife. He attempts to “prove” the thesis via a technique that scholars are now calling biofiction.

Since there can be no objectivity for this proposal, his conclusions must here be labeled as not based on fact but rather a fanciful reading of the plays and sonnets. We cannot therefore call this book a serious scholarly effort—but alas, he does. And so do his publishers and many others. We are therefore obliged to take it at least semi-seriously. Initially labeled scholarly, it became an instant bestseller, and still leads the competition in the area of Shakespeare biography.

From the preface, this scholar/author’s bardolatry steps forward, front and center.

The work [of Shakespeare] is so astonishing, so luminous, that it seems to have come from a god and not a mortal, let alone a mortal of provincial origins and modest education.

[Shakespeare] wrote the most important body of imaginative literature of the last thousand years.

To understand how Shakespeare used his imagination to transform his life into his art, it is important to use our own imagination.

—from the “Preface” to “Will in the World”

His treatment of Anne comes together in the chapter titled “Wooing, Wedding and Repenting.” Here Greenblatt resurrects a number of old ideas in the history of Shakespeare bardolatry. The nature of the argument—which, I repeat, we shall not call scholarship—is heavily laced with the following techniques.

- Employs high-handed sarcasm. Since Anne Hathaway of Stratford is described as a “maiden” by the registrar of their marriage bonds, Greenblatt bluntly responds (as if outing her): “ a ‘maiden’ Anne … was definitely not.”

- Sneeringly labels her unfit. An uneducated peasant girl such as she, if left to her devices, was detrimental to William’s development as a writer. Anne left William no choice but to leave her, so that he could remove this ball-and-chain to become the great dramatist he was destined to be.

- Invents possibilities. Although Greenblatt admits that neither parent objected to the marriage, he concludes “it is likely that in the eyes of John and Mary Shakespeare, Will was not making a great match.” No factual basis for any such imaginative conclusions are even offered.

- Cites chapter and verse from the plays to confirm that Shakespeare hated Anne, and thus must have hated the marriage. A sample:

For what is wedlock forced but a hell

An age of discord and continual strife…”

— Henry VI Part I

Greenblatt sets aside thirty pages of his book in making the case, not for a Tortured William, but for an Evil Anne, and not really using standards of scholarly research, but rather sarcasm, schoolboy hunches, and his own feelings-based analysis.

Stephen Greenblatt

In other words, the author is our modern day Edmond Malone. He quotes from comedies like “Love’s Labor’s Lost” and histories like “Henry VI Part III,” and many others, employing this same trick of argument. He flits from one play to another, cherry-picking lines that make his case, then ignoring or explaining away others. In describing a scene in “Twelfth Night” where characters are scandalously whispering amongst themselves, Greenblatt ends with: “These may have been precisely the feelings evoked in Shakespeare when he looked back upon his own marriage.”

To bolster this opinion, Greenblatt moves, not to scholarship, but rather to unspoken intent:

Between his wedding license and his last will and testament, Shakespeare left no direct, personal trace of his relationship with his wife …. From this supremely eloquent man, there have been found no love letters to Anne, no signs of shared joy or grief, no words of advice, not even any financial transactions.

Oddly, in saying this, Greenblatt chooses not to tell his readers an important fact of which he himself should be fully aware. Specifically, we have no letters from William to anyone. We do have some financial transactions, but, as would be expected, there is no evidence of affection or disaffection.

It is odd that not finding something somehow trumps finding something. In this loopy logic we progress from “guilt by association” to “guilt by not finding.” As there may still be doubters among you, please allow me to share Greenblatt’s most egregious argument for the “not finding” finding.

It is, perhaps, as much what Shakespeare did not write as what he did that seems to indicate something seriously wrong with his marriage.

Using this reasoning, Greenblatt cites ever more “not-findings” of evidence, cited from the plays in a chain of arguments specifically about the interpersonal relationships of his characters.

- “Winter’s Tale” suggests that the marriage of Leontes and Hermione “could not sustain … the emotional, sexual and psychological intimacy … that it once possessed” [implying that Shakespeare must also have lost passion for his own wife]

- There is “nothing to explain the wholesale absence of spouses from the plays”— [specifically, there is no Mrs. Lear, no Mrs. Shylock, and no Mrs. Prospero]

- In “Measure for Measure” and “All’s Well That Ends Well” and “the great succession of comedies that Shakespeare wrote in the latter half of the 1590s, there is scarcely a single pair of lovers who seem deeply, inwardly suited for one another”— [well, after all, they are comedies].

*

Near the end of the chapter, Greenblatt plays his most desperate hand. Who, other than bardolaters, would have guessed that all along we were talking about virginity?

- [Like Hamlet, Macbeth and Othello,] “… Shakespeare may have told himself … that his marriage to Anne was doomed from the beginning. Certainly he told his audience repeatedly that it was crucially important to preserve virginity until marriage.”

- And in “Romeo and Juliet,” Juliet firmly reminds Romeo that, in Greenblatt’s words, “her maidenhood was not up for discussion.”

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the prosecution’s arguments are specious. Throughout history writers have explored passionate strife between husband and wife. The theme is universal. In no way does it prove that the writers themselves hated their spouses, or that their spouses hated them.

Your honor, I move to request a mistrial.

Germaine Greer “Shakespeare’s Wife” (2008)

All biographies of Shakespeare are houses built of straw, but there is good straw and there is rotten straw, and some houses are better built than others. – Introduction

It would not be fair for us to exclude one of the most strident and well-known culture critics from our book survey. This is, after all, the Germaine Greer—the notorious rabble-rousing feminist from the late Sixties, author of the “The Female Eunuch” (1970), a woman known for outrageous utterances, a contrarian never shy of stirring the pot, one who has always felt comfortable in the limelight.

It would not be fair for us to exclude one of the most strident and well-known culture critics from our book survey. This is, after all, the Germaine Greer—the notorious rabble-rousing feminist from the late Sixties, author of the “The Female Eunuch” (1970), a woman known for outrageous utterances, a contrarian never shy of stirring the pot, one who has always felt comfortable in the limelight.

But I was stunned to learn that Greer was, and still is, a Shakespeare historian. Her Ph.D. thesis from Cambridge was “The Ethic of Love and Marriage in Shakespeare’s Early Comedies” (1968). Over a long career in many fields, she also wrote the book “Shakespeare” (1986) for the Oxford University’s Past Masters series and has since contributed Shakespeare articles and commentary to several scholarly publications and consortiums. In this capacity, she has served on university faculties around the world.

Germaine Greer

Her book “Shakespeare’s Wife” is indeed quite scholarly, and yet also a mass market book. It is readable and witty and, most significantly, critically well received. The book is also modestly feminist, primarily in the sense that she argues for a reasonable and historical approach, with reference to how wives and husbands understood each other in sixteenth century Britain. Greer does quote now and then from primary sources, and from William’s poetry and plays, but the book is largely a methodological argument, displaying her scholarly cred by drawing conclusions from a multitude of cultural studies, especially of everyday life in Elizabethan times, and in the activities of the average Elizabethan villager and city dweller.

Evidence-Based Research

Greer challenges many traditional beliefs, especially assumptions of literary scholarship based on either absence of confirmation or the overlooking of social research and/or common traditions.

- Typical Claim: William stayed in school until age 14.

Greer’s Response: it is likely, but “the records have not survived.” - Typical Claim: William might have apprenticed with his father.

Greer’s Response: “There was little point in giving a boy a grammar school education if the ultimate intention was to apprentice him to a manual trade.” - Typical Claim: Well-known historian Katherine Duncan-Jones writes that Anne “exploited her freedom [as a woman over age 21] to consort with the local youth” and William’s “dalliance with her … was probably his first experience of sex.”

Greer’s Response: “There is no reason to believe that Shakespeare’s vocal cords were underdeveloped.” - Typical Claim: The bardolaters virtually dictate that Anne’s pregnancy was shameful and humiliating for her and for William.

Greer’s Response, using studies of marriage in the sixteenth century: “For an honest woman, who was not free with her favours, premarital pregnancy was no disgrace at all.” - Typical Claim: The bardolaters maintain that Anne’s pregnancy was hidden and would have been out of the ordinary for a conventional marriage.

Greer’s Response: “Elizabethan parish registers show many christenings within three or four months of the parent’s marriage, and the register of Holy Trinity [at Stratford] is no exception.”

Greer suspects that Anne may have already been “in service” and no longer living in Shottery but admits there is no proof. On the other extreme, by English law, Anne could have been placed in service when she was six or seven. What studies have shown is that many women who did go into service did not find husbands.

So Greer takes a less-loaded, more commonsense approach.

As we have seen, the Shakespeares and the Hathaways knew each other, so there is no need to suppose that one day, quite by chance, Shakespeare wandered too close to Shottery and got snared by ‘a homely wench’. Ann was no wench; even if she had been in service, she would have been employed at a higher rate than a mere wench.”

– Chapter 3

The Wedding Alliance

In those days, Anne, as an adult, would at her wedding speak for herself. William, as an underage dependent, would be required to have his parents sign for him. Customarily, parents of means were expected to arrange a “suitable match” for William. The same would hold true for the wife if her parents were still alive. To do this properly, parents on both sides would generally have to put up property.

The problem, Greer points out, is that by 1582 John Shakespeare had gotten himself into a heap of debt and had even mortgaged his wife’s land holdings, which had been Mary Shakespeare’s sole inheritance. Anne’s “holdings” were above that of William’s parents and amounted to a slightly-better-than-modest endowment from her father’s will to be provided at the time of her marriage. On William’s side of the match, both money and property were seriously wanting.

Greer points out that single pregnant women without a handfast from their future husband were often coerced into naming the husband of the unborn child. If the husband fled or otherwise did not respond, he was excommunicated. The father would in all cases be expected to support the child. If the mother never married, however, the child could eventually be transferred to the household of the father.

In the following quote, Greer lambastes Greenblatt for not really knowing the first thing about Elizabethan marriage mores.

If Shakespeare had denied paternity, Ann could have been punished for being ‘unlawfully pregnant,’ possibly publicly whipped, certainly made to stand in front of a congregation on a Sunday, clad in nothing but a white sheet. When her time came the midwives would have refused to help deliver her until in extremity of fear and pain she screamed out the name of her child’s father, in which case Shakespeare too would have been disgraced, especially if she died …. Faced with such evidence, one wonders how Greenblatt could allow himself to say that ‘an unmarried mother in the 1580s did not, as she would in the 1880s, routinely face fierce, unrelenting social stigmatization.’ What the unmarried Elizabethan mother had to face was persecution so intense that it verged on savagery.

After the Wedding

Since there were so many variations on traditional weddings, and because we know nothing about the goings on during Anne and William’s marriage day, Greer breaks down all the possibilities, with references drawn from many contemporary texts, as well as from William’s plays such as “Taming of the Shrew” and “As You Like It.”

If Will and Ann could give their neighbors no wedding feast, it would have been simply because there was no one to pay for it. Ann’s parents were dead, Will’s parents were broke, and they needed every penny they could scrape together for somewhere to live.

On Greenblatt

Greer several times ridicules Greenblatt for sloppy scholarship, especially in his generalizing from what he knew only of the playscripts themselves. At one point, Greenblatt claims that after their marriage William and Anne and Susanna moved in with William’s parents and brothers and sisters—and “however many servants they could afford.” To this, Greer casts her eye-roll with a view to what the real life of a glove maker might be.

John Shakespeare was not a nineteenth-century captain of industry but a Tudor artisan. The house in Henley Street may have been ‘spacious’ but if Shakespeare was still working as a glover it should also have been the site of the workshops where his workmen treated the stinking skins. … Any servants kept by the Shakespeares would have been employed in the business, not in domestic niceties. Nursemaids and ladies’ maids were not to be found in the houses of Tudor tradesmen.

When Greenblatt points to William’s plays showing unhappy married couples, Greer counters that is the case with all great plays, and in all of literature.

We get inside marriages only when they are dysfunctional.

When Greenblatt sides with William (over Anne) by using the bardolater viewpoint, the intended implication goes something like this: the future playwright was justified in leaving Anne with no intention of returning. Greer ruefully summarizes:

[This] scenario is worse than grim: son is seduced by ugly harlot, forced against his will to marry her, with no option but to bring her back to the parental home, where child is born, then twins, then he abandons everyone, his wife, his children and his parents. If this is what happened Ann’s life could hardly have been worth living …. Such behaviour would have been considered so reprehensible by all the people Shakespeare had grown up with that Will could hardly have wanted to show his face in Stratford again.

Usually when a husband abandons a wife with three small children, we are less concerned for his disappointment, frustration and loneliness than for hers. In this case, the absconding husband can do no wrong; it is the inconveniently fecund woman who has brought desertion upon herself.

…. it is Shakespeare who gives voice [in the plays] to the yearning of the women who wait out the weeks and months for the return of the man they love.

Maggie O’Farrell “Hamnet” (2019)

- Fact: In his will, Anne’s father Richard Hathaway refers to his daughter as Agnes, not Anne.

- Fiction: In this novel, Agnes is Anne’s private family name, one that she lovingly shares with William.

… with that near-hidden, secret “g.” The tongue curls toward it yet barely touches it. Ann-yis.

Opening Scene

… a late summer morning in 1596. Hamnet in a panic.

The boy is frantically looking anyone who can help his twin sister Judith. He finds her alone in the house, returned to bed, fallen into some kind of fitful, anguished sleep. She is frightfully feverish. She won’t awaken. An eerie sight greets him.

… [a] swelling at the base of her throat. Another where her shoulder meets her neck. He stares at them. A pair of quail’s eggs, under Judith’s skin. Pale, ovoid, nestled there, as if waiting to hatch.

We readers know. The “eggs” are buboes—a sign of the black plague—but it is a sight wholly unfamiliar to Hamnet, he has no clue, he has never seen anything like it. He begins to panic. He worries that he cannot find a way to bring Judith back to consciousness.

At that moment, his mother Agnes is a mile away in Shottery. She had been summoned earlier that morning by her brother Bartholomew who had noticed something amiss with Agnes’ honeybees. He had dispatched a shepherd’s boy to tell her the bees had left their hives. The messenger reports that they are massing in the trees, near the border of her property.

Just then Hamnet arrives at the doctor’s house. Through a crack in the door he fretfully tells the doctor’s wife about Judith and the buboes. The doctor’s wife refuses to let him in. He pleads with her. He will come, she says. Fretfully the boy hurls himself home.

Hamnet’s grandmother Mary and his sister Susanna are at the market, just one street over, unaware of the crisis. They seesaw through the stands, greeting folks, carrying baskets of gloves, hawking their wares.

As Hamnet returns, Judith is moaning, her eyes fiercely closed, her face burning. As we transfer into the soul of this girl, she is clutched by a dream. Tears course down her feverish cheeks. Suddenly she convulses.

Maggie O’Farrell

… was born in Northern Ireland and has since lived in Wales and now resides in Scotland. She has been writing novels for two decades. Her eighth novel “Hamnet” was awarded the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2020 and the National Critics Circle Award for Fiction in 2021. Amblin Entertainment announced a forthcoming movie is in the works.

Maggie O’Farrell

The book has what we might call a shape-shifting narrative, a world where the author deals out the story’s narration among each of its central characters. If you try to Google that, you’ll be soon bumping into scholastic concepts such as “multiple planes of consciousness”, “narrative frames”, “character constellations”, and (my favorite) “multiperspectivity.”

Nowadays this technique is the established landscape for a number of historical novels. The scenes are witnessed pluralistically, through the perspective of multiple lives reimagined, quickened and enlivened. The suspense is built not so much by plot as by each character’s perception. The unnerving but effective use of “third person present tense” is often used for each point-of-view and propels the narrative into constant urgency.

Time itself moves around a bit. In this book we find ourselves ticktocking back and forth, earlier and later, hurled about within a span of eighteen years, from 1596 (Hamnet’s nightmare scenario) back to 1582 (the wedding), then back to 1596 (Hamnet again), and eventually to later years 1597-1600. The effect is eerily like consciousness, reminiscent of the way the mind reaches back in time, and returns to the present, haphazardly, without warning.

Agnes

… is rumored around Stratford to be a bit touched, and widely known to be intrigued by the power of wild herbs and mysterious concoctions. Her reputation evokes whispers throughout the town and the countryside. She has a “witch’s garden.” She is in her mid-twenties, still unmarried, still at home.

Agnes/Anne: A Modern Take

How, they wonder, did she manage such success with her medicinal treatments? Where did she come from? Is she sorceress or forest sprite?

Agnes knows that her family and the in-laws and the citizens will never understand her. This headstrong woman seems imposing, always in motion, roaming in the woods, harvesting wild herbs, flowers, roots and weeds in the fields, storing them as powders and salves, browsing at the marketplace, playing with her children. She dabbles in folkloric cures, sells purgatives, brings jellies and potions to those in need—and on her brother’s property raises chickens for eggs and meat, stores garden tomatoes and spuds for year-round food.

William

… is growing restless. His father and mother disapprove of his secretive writing, his insatiable appetite for poetry, his dim prospects. All of which fire his dour moods, darken his privacy, predispose him to a chronic unhappiness. It is not only that he has a dead-end job—a hireling, a mere Latin tutor for the local children—but, as he pointedly confesses to Agnes, “I cannot abide waiting.” At home in Stratford, William’s misery grinds into hopelessness—that is, until he works out a ruse in the form of a business offer to his father. Yes! He will get himself installed in London as an agent, to expand John’s business of leather goods in the international city … somehow. His mother Mary is aghast. His wife Agnes purposely does not listen.

Once in London, William escapes the onerous baggage of faithfulness to his parents. In the historical record we find no mention of this road to success, but in this book, the theater beckons. Still, William writes home from the great city of fog and pandemonium. His sister Eliza and the boys read aloud from the letters, their father’s stories and escapades all eagerly devoured.

The Family

… is largely created through backstory for each of the many characters, ever so gradually blending the results into the narrative. Susanna is querulous and resentful, half-wishing for a plague so that her father will be forced to come home. Hamnet is bookish yet loving, with his imaginative “tendency to slip the bounds of the real, tangible world around him and enter another place.” Judith is intuitive, untaught but feels the world with her fingers and her senses.

The loving, nosy, but shrewd Eliza guides the way. She is William’s younger sister by five years, the grounded one—always quietly observant, ever listening. She tells William that Agnes is seen around town as “fierce and savage, that she puts curses on people, that she can cure anything but also cause anything. … She can sour the milk just by touching it with her fingers.”

Hamnet

… fears Judith may not make it through. His grandmother Mary insists the traditional heat must be applied, and the race against time alone inspires the entire family to feverishly pitch in. Mary is preparing a hot fire and working the bellows, Susanna is rounding up fresh sheets and lighting candles, Agnes is climbing the stairs to carry Judith back down—each of them, at differing moments, sensing that something is still not quite right, something they are not sure of. Where is Hamnet? Did he not seem noticeably pale? Was he not here just a moment ago?

As they look for the boy, it begins to dawn on everyone that something has indeed gone terribly awry. Hamnet, wherever he is, has plunged into his own private world, a silent region previously unknown to him.

The heat in the room is unbearable … like fumes from the gates of Hell. … he seems to see, just for a moment, a thousand candles in the dark, their flames guttering and flaring, wisp lights, goblin candles. He blinks and they are gone.

Additional Sources

Books

- Peter Ackroyd “Shakespeare: the Biography” (2005)

- James Shapiro “Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?” (2010)

- Jack Lynch “Becoming Shakespeare: The Unlikely Afterlife that Turned a Provincial Playwright into the Bard.” (2007)

Articles

- Elizabeth Winkler, “In Shakespeare’s Life Story, Not All is True. In Fact, Much is Invented” The Atlantic Magazine (May10, 2019) (https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/05/all-true-and-problem-shakespeare-biography/589018/)

- Michael Lackey “Locating and Defining the Bio in Biofiction” Biography Studies, 31:1, 3-10 (2016) (https://doi.org/10.1080/08989575.2016.1095583)

Reviews of Stephen Greenblatt’s Book

- Colm Toibin “Will in the World: Reinventing Shakespeare” New York Times Book Review (Oct 3, 2004) (https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/03/books/review/will-in-the-world-reinventing-shakespeare.html)

- Christina Nehring “Shakespeare in Love, or in Context” The Atlantic Magazine (Dec 2004) (https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2004/12/shakespeare-in-love-or-in-context/303617/)

- John Simon “Bardolatry Made Easy” The New Criterion (Apr 2005) Available only via paid subscription.

Reviews of Germaine Greer’s Book

- Charles Nicholl “Married to the Myth” The Guardian (Sep 1, 2007) (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/sep/01/biography.germainegreer)

- Katie Roiphe “Reclaiming the Shrew” New York Times (Apr 27, 2008) (https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/27/books/review/Roiphe-t.html)

- Germaine Greer “Edinburgh International Book Festival” Audio Presentation” (2007) (https://www.edbookfest.co.uk/media-gallery/item/greer-germaine)

Reviews of Maggie O’Farrell’s Book

- Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado “Review: Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell” The Literary Review (https://www.theliteraryreview.org/book-review/a-review-of-hamnet-by-maggie-ofarrell/)

- Geraldine Brooks “Shakespeare’s Son Died at 11. A Novel Asks How It Shaped His Art” New York Times (July 17, 2020, updated Nov. 23, 2020) https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/17/books/review/hamnet-maggie-ofarrell.html?searchResultPosition=1

- Joanna Briscoe, “Hamnet – Immersive Shakespearean Drama” The Guardian (Mar. 26, 2020) https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/mar/26/hamnet-maggie-ofarrell-review-shakespearean-drama-son-grief-twin-sister

One Response to “Shakespeare’s Wife”

Mrs. Shakespeare and Mrs. Lacy both say thank you and well done!