Of Pea Pods and the Misbegotten

Gregor Mendel and the Mighty Pea

Once upon a mid-nineteenth century, deep in the ancient forests of eastern Europe, there lived a humble Augustinian friar named Gregor Mendel. This godly man loved flowers. And between his prayer vigils and meditations he was allowed as much time in his garden as he needed. His labor of love lasted years, peaceably tending to his beloved plants. In that space and time, nestled in the obscurity of St. Thomas’s Abbey in Brno, Austria, Mendel discovered in his solitary researches what no man had ever thought of, not even Charles Darwin.

Back in those days there were lots of educated guesses about how heredity worked, but what Mendel did was go the well—the well of research. He eventually theorized from his exhaustive analysis that the inheritance of certain characteristics, over generations, followed patterns that we now know as dominant and recessive. He discovered the LOGIC whereby some characteristics skip generations, and some appear to go away entirely. He established that each trait was either dependent or independent of others. He assumed that some changes were predictable, and yet other characteristics have their origin in spontaneous changes whose cause was as-yet unknown, but eventually knowable. Mendel recorded thousands of inherited variations and put forth his conclusion that each and every characteristic of an organism was determined by its own physical, if invisible, “factor”. It was what scientists would later call a “gene”.

Too bad Darwin did not know Mendel. They were more or less contemporaries. Darwin, of course, had delivered his own Big Bang to science in the form of a few blockbuster tomes about something called Natural Selection. Yet oddly enough, Darwin had a missing link in his grand theory—he misunderstood heredity as much as all the others of his generation. As a result he did not have an answer to how his discovery—how spontaneous changes in matter or body structure—could possibly be successfully passed to later generations. Darwin had proven that organisms responded to their environment—but he also knew that, eventually, the underlying science of heredity would be critical to the acceptance and credibility of his theories. He even claimed that a new book on the subject would be forthcoming. It never happened.

Back at the Abbey, in what is now Czechoslovakia, Mendel’s historic contribution made it only so far as one short lecture and a subsequent article in an incredibly obscure scientific journal. In fact, it was thirty long years before Mendel was even “rediscovered” by later biologists who themselves had done pretty much what he had done, without quite knowing that Mendel had already done it. Once they learned, of course, they quickly credited him, and publicly confirmed his hypotheses.

Hit-and-miss, trial and error—it is the way of all science—a kind of lurching forward. And of course there was no science of genetics in the 1860’s to shed any light—that too evolved. Biology in the mid-nineteenth century was mostly a science of categorization. Chemistry and physics appeared cordoned from each other as well. But within about fifty to sixty years of Gregor Mendel’s paper, as the sciences began to confirm each other’s hypotheses, and their relevance to each other became inescapable, the disciplines eventually did come together into what is now known as the “Modern Synthesis” of evolutionary biology.

In this way eventually the theory of genes settled into the greater chemistry of organic matter. And as researchers learned more about the known sugars and proteins and all manner of squiggly somethings jiggling around in our cells—the real work commenced. A number of experiments were done to logically include and exclude what became known to us (if not entirely visible) as the essential ingredients of life, i.e. DNA. And from those years of research by many scientists, eventually Watson and Crick cracked the code and the structure of the thing. It’s instructive to point out that one of their later models, prior to their success, was actually a triple helix. But from their many failures and their major successes—their lurching forward—in our day the molecular basis of evolution has finally become a science all its own.

Siddhartha Mukherjee “The Gene: An Intimate History” (2016)

Science, as we know, not only lurches forward. It can sail backward as well, and may tack sideways—and can even be hijacked.

Pulitzer-Prize winning author Siddhartha Mukherjee has more than made up for my lack of specificity in his latest nearly 600-page monster of a book, “The Gene: An Intimate History” (2016)—a compendium of fact, trivia, history and labyrinthine musings on the science of genetics. I’d be a fool if I tried to distill any of it within a blog post. But of course, as you know, that never stopped me before.

I can tell you I am no scientist. So of necessity, I defer to Mukherjee who tells the tale of still another, somewhat warped and parallel universe to that of the true researchers.

In 1883, one year after Charles Darwin’s death, Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton published a provocative book—Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development—in which he laid out a strategic plan for the improvement of the human race. Galton’s idea was simple: he would mimic the mechanism of natural selection. If nature could achieve such remarkable effects on animal populations through survival and selection, Galton imagined accelerating the process of refining humans via human intervention. The selective breeding of the strongest, smartest, “fittest” humans—unnatural selection—Galton imagined, could achieve over just a few decades what nature had been attempting for eons. —Mukherjee, p.64

It cannot be said that this Galton dude was working in an intellectual vacuum. Throughout his century, there were many, many, many efforts to explain racial superiority by rationalization parading as scientific method. For an eye-popping digest of this subject, see the article on “Scientific Racism” in Wikipedia—it reads like a freak show of pseudo-scientific claims. But I suppose if you hear something long enough, you begin to believe it. And so it was . . . with almost everyone.

In Europe and America in the 19th century, even advances in the livestock breeding had this curious effect on . . . yes, addressing a serious social problem. Which is to say, so much for pea pods; what about humans themselves? Not least of the political concerns of the day was the impact of the great migrations of slaves and refugee immigrant workers to the cities of the northern climes—and the factories and cauldrons of industrial society.

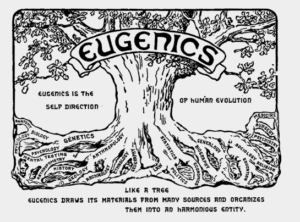

Over time what Galton set in motion was what he called a new science, and he dubbed it Eugenics, combining the Greek prefix eu —”good”—with the Greek genesis. Galton distilled his notion thus: “good in stock, hereditarily endowed with noble qualities.” Francis Galton spent a lot of time over the last decades of that century writing several books and journal articles trying to justify a theory based . . . on surveys. The self-professed statistician even issued a rather speculative equation as the underpinning of his “Ancestral Law of Heredity.” He had many detractors, of course, but a surprising number of high-profile defenders as well. The idea was simple. Design a better human being.

—”good”—with the Greek genesis. Galton distilled his notion thus: “good in stock, hereditarily endowed with noble qualities.” Francis Galton spent a lot of time over the last decades of that century writing several books and journal articles trying to justify a theory based . . . on surveys. The self-professed statistician even issued a rather speculative equation as the underpinning of his “Ancestral Law of Heredity.” He had many detractors, of course, but a surprising number of high-profile defenders as well. The idea was simple. Design a better human being.

H.G. Wells, among many others, was enamored of the theory.

Wells agreed with Galton’s impulses to manipulate heredity as a means to create a “fitter society.” But selective breeding via marriage, Wells argued, might paradoxically produce weaker and duller generations. The only solution was to consider the macabre alternative—the selective elimination of the weak. “It is in the sterilization of failure, and not in the selection of successes for breeding that the possibility of an improvement of the human stock lies.” —Mukherjee, p.74

In “The Time Machine” (1895), H.G. Wells imagined a future society where humans had inbred into a degenerative race.

Indeed, Wells had only articulated what many in Galton’s inner circle held deeply but had not dared to utter—that eugenics would only work if the selective breeding of the strong (so-called positive eugenics) was augmented with selective sterilization of the weak—negative eugenics. In 1911, Havelock Ellis, Galton’s colleague, … [said]: “In the great garden of life it is not otherwise than in our public gardens. We repress the license to those who, to gratify their own childish or perverted desires, would pluck up the shrubs or trample on the flowers, but in so doing we achieve freedom and joy for all…. We seek to cultivate the sense of order, to encourage sympathy and foresight, to pull up racial weeds by the root…. In these matters, indeed, the gardener in his garden is our symbol and our guide.” —Mukherjee, p.76

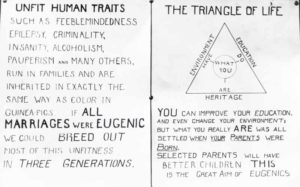

So it was that eugenics, a misbegotten notion if ever there was—and, though still controversial—became all the rage. Naturally as the pseudo-science matured, it began to abound in public discourse. Intellectually-sounding phrases were tacked onto racial jibes with the unsubtle intention to incite public sentiment. Laws and public speech soon resonated with a modern “race rationale” mixed with a kind of scientific jargon: “race degeneration”, “eliminating defect strains”, “race hygiene”, “colonies for the genetically unfit”. Councils, research institutes, and journals sprouted up, and even the American Breeder’s Association got into the act.

Over time, average people acted as if it were settled science. Almost unbelievably, by 1912, in America, there were laws authorizing sterilization for the “unfit” in no less than eight states. Their focus fell upon the broken among us: “epileptics, criminals, deaf-mutes, the feeble-minded, those with eye defects, bone deformities, dwarfism, schizophrenia, manic depression, or insanity”—and due to its institutionalization in law, this sort of nonsense became commonplace. By the mid-1920’s, in law and in the commonweal, there developed a rational basis upon which to build a kind of purified and idealist genetic purism.

Over time, average people acted as if it were settled science. Almost unbelievably, by 1912, in America, there were laws authorizing sterilization for the “unfit” in no less than eight states. Their focus fell upon the broken among us: “epileptics, criminals, deaf-mutes, the feeble-minded, those with eye defects, bone deformities, dwarfism, schizophrenia, manic depression, or insanity”—and due to its institutionalization in law, this sort of nonsense became commonplace. By the mid-1920’s, in law and in the commonweal, there developed a rational basis upon which to build a kind of purified and idealist genetic purism.

We have no less than the United States Supreme Court to thank for their ultimate blessing of the practice of sterilization. In the early part of this century, we forget that certain words now utterly verboten—”feeble-minded”, “moron”, “mental defective”, “imbecile”—were officially used by doctors and superintendents of mental institutions to categorize and diagnose various levels and types of mental illness. Persons were regularly sterilized to keep them from “breeding again” or “befouling the gene pool.”

But in 1926, a few heroic lawyers decided to take one particular case from Virginia. They appealed a sterilization verdict of one Carrie Buck, on the basis of the disputed science of eugenics itself.

The U.S. Supreme Court took scarcely any time to reach its decision on Buck v. Bell. On May 2, 1927, a few weeks before Carrie Buck’s twenty-first birthday, the Supreme Court handed down its verdict. Writing the 8-1 majority opinion, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. reasoned, “It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. —Mukherjee, p.83

Jaw-dropping. Well, I needn’t elaborate on the outcomes. We all know what happened in the 30’s and 40’s. Still, it is interesting to observe that horrible ideas don’t just arise all at once. No, it was not out of the blue but rather took 50 years to go from Galton’s treatise to our Supreme Court decision.

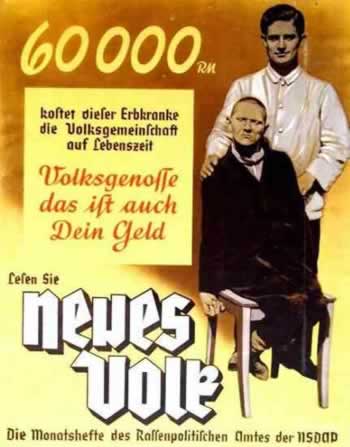

And a few years later, even In Nazi Germany, when there had to be a path to acceptance, it took over six years to go from public embrace of “sterilization of the unfit” to the programmed euthanization of the unfit and, finally, “racially inferior”. You’d have to say that if Josef Mengele was the monster, then Francis Galton, H.G. Wells and their colleagues were the mad scientists who conceived the ill-gotten child.

And a few years later, even In Nazi Germany, when there had to be a path to acceptance, it took over six years to go from public embrace of “sterilization of the unfit” to the programmed euthanization of the unfit and, finally, “racially inferior”. You’d have to say that if Josef Mengele was the monster, then Francis Galton, H.G. Wells and their colleagues were the mad scientists who conceived the ill-gotten child.

As for the legal side, apparently the “science” was never at issue—it was, if anything, taken at face value by the judges. In fact the principle of law used by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. to justify sterilization was . . . say again? . . . compulsory vaccination.

We like to say we are above all that. We are a nation of laws. But, in and of itself, this is in no way a guarantee of justice.

Leave a Reply