Moonlight and Innocence

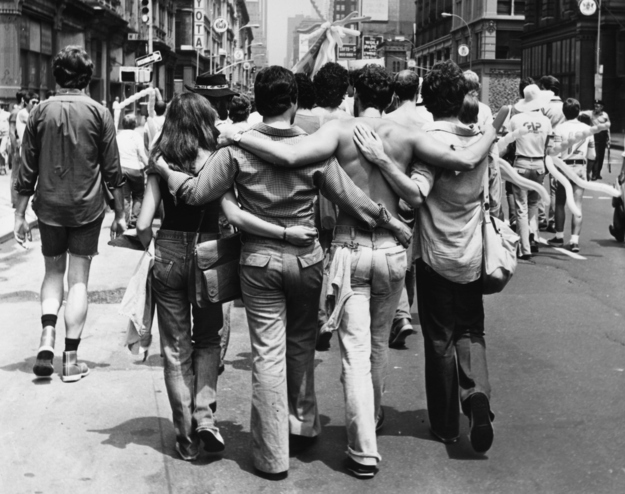

The Gay Pride Parade, 1970

The gay liberation thing started when I was still under the drinking age. I met my first “straight-up” self-declared homosexual in 1967. Before I knew anyone who was “gay” or had “come out of the closet,” there was this Daniel Butler, friend. A courageous friend, I always thought—for, at that time, admitting homosexuality was akin to saying you were a communist. Some people even got committed.

I was not gay, but Daniel often said with a smirk he would not hold that against me. There were many sides to him, two of them sort of fascinating. One was the boyish if somewhat homely kid from a small town with a dark and often secret life, and a rarely revealed tortured past with a family and father that had written him off. The other was a creative writer and intellectual, a lover of books and culture and movies and art, and especially anything contemporary that rocked the establishment of the normal. You didn’t have far to look, he said, and he always pointed this out to me by citing his latest readings: Warhol, Burroughs, Hunter S. Thompson—some of the brightest artistic lights of the time. Daniel was not himself a trailblazer but he enthusiastically followed the vanguard of the counterculture.

Daniel was my punched ticket into a world of opposition and oppression, a world that I might never have otherwise known. He and I would regularly run into each other around the University, and a few years later we sometimes shared living space when one of us needed a roof over his head. He joined antiwar protests and helped to found the first Gay Student Alliance on campus. He could be quite the leftist scold. I now know his life was not dissimilar to that of the writers I present here today, for he had grown up gay from his earliest memories. I never did learn much of his private misery, he preferred humor—but it eventually all came down to yet another side of Daniel, the guy who fell madly in love with drugs and the underground scene.

There’s a well of hurt in that buried life, but Daniel is long gone. It didn’t have to happen, but it did. For a glimpse into that anguish, we need to turn to recent sources.

Edouard Louis “The End of Eddy: A Novel” (2014)

This young French author is as much firebrand as tattletale, and his book—which, by the way, is not so much “a novel” as what today is called autofiction—is very much in the tradition of the autobiographical writings of Edmund White and Andre Gide. Louis tells a story that is as difficult to read as it is to put down. Every line of it, he has said, “is true.”

This young French author is as much firebrand as tattletale, and his book—which, by the way, is not so much “a novel” as what today is called autofiction—is very much in the tradition of the autobiographical writings of Edmund White and Andre Gide. Louis tells a story that is as difficult to read as it is to put down. Every line of it, he has said, “is true.”

Louis was named Eddy because of the American television shows his father watched: “a tough guy’s name.” He was born into a working class family, an effeminate boy with “fancy ways” that his parents sincerely tried in their own insensitive fashion to disabuse him of. His behavior embarrassed them “because all the village was talking.” They winced at these “feminine inflections” and “queeny gestures” … come on Eddy, can’t you stifle it a bit?

They thought I’d chosen to be effeminate, as if it were some personal aesthetic project that I was pursuing to annoy them. And yet I too had no idea why I was the way I was. I was dominated, subjugated by these mannerisms, and I had not chosen that high-pitched voice. I had not chosen my way of walking, the pronounced, much too pronounced, way my hips swayed from side to side, or the shrill cries that escaped my body—not cries that I uttered but ones that literally escaped through my throat whenever I was surprised, delighted, or frightened.

-p. 16

The village and the resentments—these are as much characters in the book as the characters themselves. Masculinity, and the striving to attain it, is the end-all and be-all. As a lad in the rural rustbelt of northern France in the 1990s, he was a boy who had no place to fit in, a boy who was beaten almost daily at school, punched, spat upon, humiliated around other boys, told to run so they could laugh at his gait, his head thrown upon a brick wall time and again. Two boys in particular were his torturers. We know them in the book as tall redhead and short hunchback.

They came back. They liked how out-of-the-way the place was where they knew they could find me without being caught by the monitor. They waited for me there every day. Every day I came back, as if we had an appointment, an unspoken contract. … There was just one idea I held to: here, no one would see us, no one would know. I had to avoid being hit elsewhere, in the schoolyard, in front of the others, I had to keep other kids from thinking of me as someone who gets beaten up.

-p. 25

Our view of Eddy’s family is an endless cycle of violent thrusts and jabs as well, both physical and psychological. There were many fights. The father, a factory worker is seen fighting at the pub, but he is a man who rarely abused Eddy, except for egregious behavior, except to show his disappointment. Eddy’s step-brother, a violent drunkard himself, and living apart, did regularly try to lash out, but the primary scoundrels were the schoolboys.

I could smell their breath as they got closer, an odor of sour milk, dead animals. Like me, they probably never brushed their teeth.

– p.8

A whistling perforates my eardrums as my head hits the brick wall, and I can barely keep my balance. Endless headaches would paralyze me for days at a time. … They grabbed me by the hair, always with the same relentless singsong of abuse faggot, cocksucker. Dizziness, clumps of blond hair in the hands. The fear, therefore, of crying and making them even angrier.

– p. 26

Eduoard Louis in Paris

What we feel along with Eddy are the interiors of his life. The meanness of a small factory town with all the small-minded prejudices and cruelty that go with it. The mistrust of doctors and teachers and professionals of any kind. The alcoholism (they all drink pastis, a sort of modern substitute for the formerly abominable absinthe). Every family member’s vulnerabilities and regrettable characteristics are felt.

We are shocked but we root for Eddy. Louis has a regenerative spirit and a transparency that is invigorating. He writes with honesty and has a clever, often charming way of dishing out a run-on sentence to combine his own recollection with his character’s way of speaking (shown in italics). As in this chapter titled “Portrait of My Mother from the Stories She Told”:

There was the shame of living in a house that seemed to crumble a little more each day It’s not a house it’s a fucking dump.

In the end maybe what she was trying to say was I couldn’t be a lady if I tried. – p.59

The many little resentments spoken of with understanding and affection help us empathize a bit with his parents. A shocking confession by his mother of a mishandled miscarriage illustrates the tragedy of ignorance. So while the book is painful to read, his own life is not entirely horrible. He is not unappreciative of his parents and his friends, and in a plain-spoken but endearing style, he is capable of fond remembrance, from scenes of his country childhood and the occasional pleasant moments in the landscapes of his youth:

the long walks in the woods, the shelters that we built there, the fires in the fireplace, the warm milk fresh from the farm, the games of hide-and-seek in the cornfields, the peaceful silence of the small streets …, the apple trees, the plum trees, the pear trees in every yard, the explosion of fall colors, the leaves that blanketed the sidewalks until our feet were lost … – p.66

But things get worse. In two, back-to-back harrowing chapters titled “The Shed” and “After the Shed”—Eddy and a friend are fooled by two of his buddies into a nightmarish game of boys playing girls, and the upshot is that over a series of afternoons he succumbs to being sodomized by his own 15-year-old cousin—and then, and worse—being found out, and beaten by his father—and then, far worse than that—his buddies making it known all over school that the buggering in the shed was really Eddy’s doing, the faggot’s plot to despoil them. Tortured mercilessly at school, Eddy was shockingly but 10 years old at the time.

Yet suddenly, for the first time in his life, he felt a new sensation.

I had to get away. But early on it doesn’t occur to you to get away, because you don’t know that there’s anywhere out here to escape to. You don’t even understand that flight is an option.

-p. 142

So he starts over again at curing himself, this time going further by trying to be Eddy “the tough guy.” He was going to prove them all wrong. And he would make good.

I would have to watch the gestures I made while talking, I’d have to make my voice sound deeper, to devote myself exclusively to manly activities. More soccer, different television programs, different CDs to listen to. … Living a lie was the only chance that I had of bringing a new truth into existence. -p. 142-143

But the pretense only extends his agony in a series of embarrassing attempts to make it with the girls. By the end of the book, he has reached the end of himself as well. Thanks in large part to a scholarship at a school for the arts, he heads out to a better place.

Eduoard Louis today

In France the book has sold well but remains controversial for its honesty. Louis has done a number of popular interviews. The English translation of “Eddy” was delayed until 2017, but a movie is now in the making for next year.

The phrase “End of” in the title translates literally; but in French it is rather more a figure of speech meaning not so much “end of” as “doing away with” or “casting off”. Such is the upshot to this unfinished story, that Eduoard Louis leaves his life as Eddy, his former village-body, if you will, as if it were but a chrysalis.

Barry Jenkins & Tarell Alvin McCraney

“Moonlight” (2016)

The unfortunate, if deliciously mistaken, announcement that “La La Land” (2016) won the Oscar this past February was more than ironic. Consider that this exhilarating happy/sad cotton candy musical for a post-truth era had caught not only our nation’s movie-going fancy, but had also received a whale of eye-rolling disdain. And why? Well, for many reasons. But among them: a stereotypical depiction of a white jazz pianist who fronts an otherwise solid ensemble of capable black musicians.

Hopefully you recall that “Moonlight” was the real Oscar winner (finally, a wholly deserving selection). But let us “compare and contrast” the opening scene of “La La Land” with the opening scene of “Moonlight.” What we have here is a Tale of Two Realities: (1) a wildly funny dance number staged upon the bridge of a freeway traffic jam in L.A. vs. (2) a terrifying foot chase of a little boy running from a bullying trio of older brutes intent on tormenting him with rocks and pipes and sticks and angry slurs, threatening physical violence.

Based on a searing play and revised film script by Tarell Alvin McCraney, and beautifully directed by Barry Jenkins, this is the story of a boy whose mother is a crack addict, and who himself is an outsider from the start. This amazing offering is the only Academy Award-winning motion picture whose cast, director, and screenwriter are entirely black. Unfortunately, it is also the only such picture whose gate receipts ranked among the lowest in its award-giving history.

Based on a searing play and revised film script by Tarell Alvin McCraney, and beautifully directed by Barry Jenkins, this is the story of a boy whose mother is a crack addict, and who himself is an outsider from the start. This amazing offering is the only Academy Award-winning motion picture whose cast, director, and screenwriter are entirely black. Unfortunately, it is also the only such picture whose gate receipts ranked among the lowest in its award-giving history.

Part I: “Little”

Chiron (pronounced “shy-rone”), lives in Liberty City, an almost ancient ruin of social service housing on the “wrong side” of Miami. The interiors and exteriors of this project, the local school yards, the empty-lot playgrounds, the streets and the hangouts and dreary interiors are filmed in sheer pastel, a sort of unkind light of memory past. The world is colorful, but small. The screen fills us with a tunnel vision of dread—normalcy as it must seem for all poverty-stricken children of our world.

Chiron (pronounced “shy-rone”), lives in Liberty City, an almost ancient ruin of social service housing on the “wrong side” of Miami. The interiors and exteriors of this project, the local school yards, the empty-lot playgrounds, the streets and the hangouts and dreary interiors are filmed in sheer pastel, a sort of unkind light of memory past. The world is colorful, but small. The screen fills us with a tunnel vision of dread—normalcy as it must seem for all poverty-stricken children of our world.

We coast along with a boy of downcast eyes and a slinking walk. He talks hardly at all. He is called “Little” by his schoolmates. He lives with his weary mother who is sunny and intimate at times, baleful and banshee-seeming at others. She is rarely at home, though, and when at first we see her she has come from a job, wearing a colorful smock of some indeterminate pattern that screams “healthcare worker.”

Thus mostly alone, Chiron makes do. He ekes out his own meals, heats his own bathwater in a large stewpot on the stove, walks drudgingly around school. He is a tiny version of the other boys, scrawnier, bonier, with a long neck and a funny way of walking. “Hey, Little,” they call out, and that becomes his nickname. He never knows what taunts might lie behind the jesting sneers. When he does manage to play with the other boys, he is often purposefully pushed to the ground in the “rough and tumble” of their regular pile-ons. His best and seemingly only friend is Kevin, who shows him how to scrap it out. He likes playing with Kevin.

Thus mostly alone, Chiron makes do. He ekes out his own meals, heats his own bathwater in a large stewpot on the stove, walks drudgingly around school. He is a tiny version of the other boys, scrawnier, bonier, with a long neck and a funny way of walking. “Hey, Little,” they call out, and that becomes his nickname. He never knows what taunts might lie behind the jesting sneers. When he does manage to play with the other boys, he is often purposefully pushed to the ground in the “rough and tumble” of their regular pile-ons. His best and seemingly only friend is Kevin, who shows him how to scrap it out. He likes playing with Kevin.

But it is a world we rarely see far beyond. It is the obverse of the unreachable, unattainable world of real work with money to spend. In fact, the world of cars and pocket cash is owned primarily by “the suppliers” or “trappers” on the street. Even the hustlers hanging out there, waiting for the buyers to come along, selling all manner of drugs, must bide their time and pay their dues, so that they may be next in line for the big opportunity.

It is a Cuban supplier named Jose who finds Chiron hiding in a burned-out apartment and takes a shine to him. Over time, and against the wishes of Chiron’s mother, Jose finds time to feed the boy. Jose teaches him to swim. Jose takes him out in the car. Jose is bar none the best role model Chiron has. He tells Chiron that once an old lady found him and his friends on the beach in the light of a full moon. “In moonlight,” she said, “you boys are blue.”

It is a Cuban supplier named Jose who finds Chiron hiding in a burned-out apartment and takes a shine to him. Over time, and against the wishes of Chiron’s mother, Jose finds time to feed the boy. Jose teaches him to swim. Jose takes him out in the car. Jose is bar none the best role model Chiron has. He tells Chiron that once an old lady found him and his friends on the beach in the light of a full moon. “In moonlight,” she said, “you boys are blue.”

And on occasion, Chiron even talks.

Chiron: “What’s a faggot?”

Jose: “You ain’t no faggot.”

Chiron: “How do I know?”

Jose: “Oh you’ll know.”

Jose’s girl:“Yeah you’ll know.”

Part II “Chiron”

Fast-forward … 8 years. Chiron is in high school. He is now tall, but still lanky, still painfully awkward, still slouching, still a daily target for the roaming pack of demonic boys. His jeans are too tight. He sticks out, and is even called “Black” by his still-best-friend Kevin, but never really understands why. Kevin minds his Ps and Qs, never, ever publicly acknowledging or demonstrating that he and Chiron are friends. At school Chiron is slugged and jammed and slapped around in the hallways and doors, primarily at the bequest of Terrel, a sneering, threatening, braided attack dog of the gang. Threats are constant, often occurring without any explanation.

But Chiron has dreams, too many to count. The wider world is opening itself to him. On the other hand, his mother, who we last saw free-basing in a car with another man, is now so strung out she has become a prostitute and must steal cash from Chiron who gets his own little bit of money from Jose, by now his stand-in parent.

But Chiron has dreams, too many to count. The wider world is opening itself to him. On the other hand, his mother, who we last saw free-basing in a car with another man, is now so strung out she has become a prostitute and must steal cash from Chiron who gets his own little bit of money from Jose, by now his stand-in parent.

In time, Chiron and Kevin rendezvous at the beach late at night. Kevin has a seriously big joint. They share. Have some laughs. Chiron admits: “I want to do a lot of things that don’t make sense.” They lean in. They kiss awkwardly. In short order they make out for the first time.

But for this they pay dearly at school. Kevin is thuggishly taunted by Terrel into slugging Chiron, and this Kevin does, so as not to lose face. The other boys leap in around them on the school patio. Kicks, punches, stomps. Chiron is left badly beaten, bleeding on the school grounds. His face is a mess. It’s an unsaid but foregone conclusion that no one will snitch, least of all Chiron. And, instead of cooperating with the police, Chiron himself takes matters into his own hands, eventually charging into a classroom and clobbering Terrel with a chair. Chiron is hauled off by the police.

Part III “Black”

Fast forward … ten years. Chiron is out of jail, “trapping” in Atlanta. He has made his way to the top. Still a man of few words, he has become lean and mean, and like Jose before him, is now a body builder and a supplier. Kevin calls him, at night, out of the blue. Chiron is stunned. They haven’t talked in all that time since the senseless beating.

Fast forward … ten years. Chiron is out of jail, “trapping” in Atlanta. He has made his way to the top. Still a man of few words, he has become lean and mean, and like Jose before him, is now a body builder and a supplier. Kevin calls him, at night, out of the blue. Chiron is stunned. They haven’t talked in all that time since the senseless beating.

Thinking of taking a trip back to Miami, Chiron stops to see his mother, now living/working in an institution. She says: “Sure, I fucked up, but your heart doesn’t have to be black like mine, baby.” There is, we sense, the possibility of change. Perhaps hope, perhaps for the first time in Chiron’s life.

McCraney and Jenkins on location at Liberty City, Miami, site of the movie

Much of the music for this picture is pure power in the mode of “chopped and screwed” tracks, achingly beautiful, some of it classical-sounding but actually crafted from the slowing of recorded chamber music—a groaning cry and wail of soundboard manipulation. So little dialog, such anguished music.

There is, of course, a bit of rap as well, but often slowed down, and while the effect has become something of a popular sensation, the movie soundtrack became for me a kind of secondary narration itself, as if the music were providing the story of emotional tearing, reflected in the deep river of Chiron’s burden.

When finally they meet again, Kevin has been “in and out,” presumably of prison. But Kevin has a job. He’s a cook. He challenges Chiron to man-up. Who are you really? he asks Chiron. Is this you?

Chiron may or may not … well, not be or do anything. He is thinking. We wonder: could it be that he and Kevin …? Not sure this work qualifies as a Bildungsroman, and not sure a memoir should be this heart-rending either.

One thing for sure. The story will bolt you to the floor of poverty and helplessness from the opening scene, and leave you swaying in the winds of limited options and homophobic terror until the fade-to-black at the bittersweet end.

What’s not for sure? Everything else. It’s real.

Read the backstory. Hear the music.

A NOTE ON E.M. FORSTER’S “MAURICE” (1971)

Over a hundred years ago, in England, in the Edwardian era, homosexuality, even the mere representation of it, was punishable by imprisonment. You have only to recall that Oscar Wilde was imprisoned in 1898 for “gross indecency”—another way of saying unrepentance was as much a crime as flaunting your trysts.

In that time, E.M. Forster secretly wrote “Maurice: A Novel” in 1913. The book, a story of two male students at Cambridge falling in love, remained under lock and key. He revised it twice, once in 1932, and again in 1960, but could never bring himself to publish. He did have doubts about its quality; but more to the point, he had even graver concerns about its legality. Hard to imagine today, this towering literary figure reckoned it could well prove to be the end of his career.

The book was published in the year after his death, 1971. It received lukewarm reviews, and soon came to be considered a “minor work”—which perhaps, on the page, it still is—in part because it was so dated. But on the big screen, 15 years after the novel was printed, “Maurice” (1987) became a must-see. Merchant Ivory, the two-man film production company best known for staging classic novels, applied their signature recipe: sumptuous cinematography combined with a great literary story, lush musical scores, spot-on casting and an international flavor unlike anything else in British-American cinema.

The book was published in the year after his death, 1971. It received lukewarm reviews, and soon came to be considered a “minor work”—which perhaps, on the page, it still is—in part because it was so dated. But on the big screen, 15 years after the novel was printed, “Maurice” (1987) became a must-see. Merchant Ivory, the two-man film production company best known for staging classic novels, applied their signature recipe: sumptuous cinematography combined with a great literary story, lush musical scores, spot-on casting and an international flavor unlike anything else in British-American cinema.

These two fabulous filmmakers were themselves a gay couple long before they started making movies in the early 1960s: Ismail Merchant, originally from India, and James Ivory, an American, combined their immense talents with the German-born British novelist Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, and together turned out an average of one movie a year for over four decades, with Jhabvala writing the screenplays for 20 of them.

It was thanks to another movie based on a Forster work, “A Room with a View” (1985)—a film that became a classic and a blockbuster—that Merchant Ivory found some financial breathing room to make whatever movies the two of them wanted. With a contemporary spirit they undertook to break new ground. The two then-unknown leads in “Maurice” (Hugh Grant and James Wilby) became overnight sensations. A new generation was empowered.

The movie is being re-released in 4k this summer. Yet the fight is still being fought, even as the world closes in. The original novel is still relevant, to my mind, and apropos to the struggle: a detailed and wonderfully literary account of how the two men come to terms with their passion and within the bounds that must not be crossed. E.M. Forster delineated the arduous twists and turns of mind and preference, but he went even further, in some ways, insisting that a relationship between any two people should be as sacrosanct as any other. In 1960, he wrote privately:

A happy ending was imperative. I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows … I dedicated it ‘To a Happier Year’ and not altogether vainly.

Leave a Reply