Libya: A Fractured Land

People do not often speak of the Middle East and literature in the same sentence. But when I think of Middle East culture, I look back to my favorite writers of that region, the Egyptians Naguib Mahfouz and Alaa al-Aswany. Somehow in their marvelous panoramic novels, these two guys captured all the textures of Arab life for me much like Garcia-Marquez and Isabel Allende did for South American literature several years before.

There are many Arab writers of such stature. There are countries that beckon. In contemporary film and literature, Turkey and Iran continue to draw my interest. But still other lands of the Arabic world seem to be missing in action from the literary scene—either in part, or entirely.

This year I was struck by a relatively new voice, speaking to us from a country that is as mysterious as its storied desert: Libya.

LIBYA UNDER THE LENS

What to most Americans is little more than a hellhole synonymous with American political mudslinging, is in truth, and in history, a country of rich traditions which, for half a century have been suppressed by a brutal dictatorship. What we are witnessing nowadays is a seething cauldron, a dangerous mix of two powerful trajectories—religious intolerance and independent thought—boiling for decades just beneath the surface of an iron-fisted rule.

Libya’s storied desert is inhabited mostly by arid and ancient mountains.

The name Libya actually goes back to the ancient Greeks. Historically, due to its climate and location, the country has contributed to the rush and tumble of wars and empires. Culturally, though, it comes off as the closest thing to an Afghanistan-of-the-West: a collection of more than 140 tribes, a motley assemblage of religious sects and local fiefdoms—with an artistic and literary output of mostly Islamic art or Arabic poetry.

This year I was struck by several news stories, and one new voice in particular—that of Hisham Matar—emerging from the stark and dangerous Libyan landscape. Following that I went looking for a film or book list, but came up nearly empty. In stark contrast to Egypt and Algeria, you really can’t find much, at least not in English—there are almost no novels or movies of Libyan origin in the major marketplaces. True, some of our own much-ballyhooed motion pictures do take place there—“The English Patient,” “The Flight of the Phoenix”—but these are narratives of alien culture from the point of view of colonizers and conquerors.

The history of Libya is peopled with traders, seafarers and farmers. In ancient times, Carthage and Phoenicia ruled the seas around Libya, as well as much of the Mediterranean coast. In the Roman era, a city named Leptis flourished, 80 miles due east of present-day Tripoli, and its forums, baths, and the famous Arch of the emperor Septimius Severus still stand as one of the best-preserved examples of ancient architecture. Vandals, Ottomans, Spaniards and Italians have all invaded over the ages. In our century, it is the British and Americans who brought their failed diplomacy.

Traditionally what Libyans cherished was their folk history, the tales and songs of an ancient, harsh and rural land. Their original ancestry is Berber—their culture, nomadic. But over the centuries they have become an Arab nation as well, notably urban now. So it is that ancient and modern must coexist.

In a piece entitled “Fractured Lands: How the Arab World Came Apart,” journalist and contemporary war correspondent Scott Anderson wrote:

While most of the 22 nations that make up the Arab world have been buffeted to some degree by the Arab Spring, the six most profoundly affected—Egypt, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen—are all republics, rather than monarchies. And of these six, the three that have disintegrated so completely as to raise doubt that they will ever again exist as functioning states—Iraq, Syria and Libya—are all members of that small list of Arab countries created by Western imperial powers in the early 20th century.

Thus, while Qaddafi didn’t need to worry about religious sectarianism — virtually all Libyans are Sunni Muslims — he did need to think about drawing into his ruling circle the requisite number of Misuratans and Benghazians to keep everyone mollified.

Rebels seize power in Tripoli in 2012

Muammar Qaddafi, himself the son of an impoverished Bedouin goatherd, ruled ruthlessly for 40 years. He was overthrown in 2012, the year following the Arab Spring. The resulting political fight has drowned the incipient voices of independent minds. Qaddafi’s rule, like Saddam Hussein’s, left warring factions to determine the future. Self-ruled or conquered, from ancient times to the 21st century, the people of this country have struggled in the midst of chaos and nationhood. Unity has never come easy.

STEVE ROSE “LIGHTS, CAMERA, REVOLUTION” (2012)

In a review in The Guardian back in 2012—“Lights, Camera, Revolution: the Birth of Libyan Cinema after Qaddafi’s Fall”—critic Steve Rose put the spotlight on film-starved Libyans in post-Qaddafi Tripoli. Many of the hopeful were attending, for the first time in years, a public screening—shorts, Libyan-made. But the reality on the ground was still sobering:

There is now a cultural vacuum in Libya, as well as a political one, thanks to the Qaddafi regime. “There was no film-making culture here at all under Qaddafi,” says Naziha Arebi, director of [the 5-minute documentary] Granny’s Flags. “He didn’t want anybody to be more famous than him.”

Qaddafi himself had a hand in two films everybody in Libya knows, both starring the ethnically flexible Anthony Quinn, and both directed by Moustafa Akkad, a Hollywood-based Syrian who went on to produce the Halloween  franchise. The first and most notorious is “The Message” (also known as “Mohammed, Messenger of God”), an expensive account of the birth of Islam. Finding no funding in the U.S., Akkad turned to Qaddafi.

franchise. The first and most notorious is “The Message” (also known as “Mohammed, Messenger of God”), an expensive account of the birth of Islam. Finding no funding in the U.S., Akkad turned to Qaddafi.

A few years later, Akkad shot “Lion of the Desert,” a biopic of Libyan hero Omar Mukhtar, who fought against the invading Italians in the 1920s. Alongside Quinn, it stars Oliver Reed, John Gielgud and Rod Steiger as Benito Mussolini. Like “The Message”, it was a commercial failure, but both films have played regularly on Libyan television since they were made.

Unfortunately for the world—and just a week before the little Libyan Film Festival premiered in 2012—an angry mob set fire to the U.S. mission in Benghazi, killing four Americans. Ironically, the attack is said to have started with a poorly made, incendiary (and fake) movie trailer called “The Innocence of Muslims” depicting the prophet Mohammed as a man with a passion for women—which became both an internet sensation and an Islamic abomination. Following the Benghazi attack, sectarian fighting broke out in major cities. Libyans at home and abroad, hoping for a political and cultural renaissance, were suddenly quieted—this time not by a dead dictator, but rather by the voices of mob rule.

Since then hope has been hiding under a burka of despair. There will be no films or Broadway musicals in Libya for the time being. As for filmmaker Arebi:

She recalls having her camera snatched from her hand in August, just across the street from where we’re talking, for taking pictures of Salafi militants demolishing a Sufi mosque – a precursor to the events that led to the death of Stevens in Benghazi.

A woman walks by a wall of graffiti in post-Qaddafi Libya.

HISHAM MATAR AND HIS THREE BOOKS

Not many of us know what it is like to experience a kidnapping. Or to have a relative or family member be “disappeared.” But that is precisely where Hisham Matar is coming from. In his first two novels and his eloquent memoir, he recounts a journey both contemporary and historical, a trip back to the cities and the country of his origin, both before and after the Arab Spring.

Hisham Matar

Matar was born in New York in 1970. His father was Jaballa Matar, a Libyan diplomat to the United Nations and former Libyan Army officer under King Idris. By the time Hisham was a boy, Jaballa left the diplomatic ranks, returned to Tripoli and became an importer and international businessman, and the family for all outward appearances seemed well-to-do. But here’s the hitch: throughout the 1970s Jaballa Matar had become an undercover dissident in the fight against Qaddafi. And the authorities were catching on.

In his three books to date, Hisham Matar tells essentially this one life story from three different angles, making his entire body of work based upon that one narrative.

*

IN THE COUNTRY OF MEN (2007)

A novel. Explores the inner life

of a boy who is ten when

his father is found to be

a covert insurgent.

Matar is often called a Libyan writer but unlike others he has lived most of his life elsewhere. He writes in English, and has made a career at several universities in England and America as a lecturer in literature. In this first book he takes us back to the still-eager pent-up spirit of the 1980s in Libya. Our focus is Suleiman, a 10-year-old boy whose father, his “Baba,” is a mysterious being who comes and goes without any stated reason.

Ever-present uncertainty is more or less the state of affairs in the opening scenes of Matar’s first novel. A boy’s growing up contrasts with the mysterious goings-on as men come and go and speak in hushed tones, and wives and uncles and their friends speak in mysterious half-sentences. Suleiman’s life is fraught with danger, but also blessed with youthful imagination. One day he makes his way to the roof where the tiles are baking so hot he has to hop, running for the shadows near the water tank.

I remember my Koran teacher Sheikh Mustafa’s story of the Bridge to Paradise, the bridge that crosses Hell Eternal to deliver the faithful to Paradise. We all will have to cross it someday, and some of us won’t make it. Those will fall into the fires below, the fires that call for them. The heat, the screaming, the flames licking the sides of the bridge, making the handrails hot to the touch. “The heat will reach some of us faster than others,” Sheikh Mustafa said, “because for some the heat, the fires of Hell themselves, will be like a voice calling.”

– p. 44-45

His imagination reverberates with the parables of religious upbringing. From the roof he escapes to a neighbor’s mulberry tree, the branches that held the forbidden fruit hanging close by.

Each berry was like a crown of tiny purple balls. They reminded me of the grapes carved into the arches of Leptis. I decided that mulberries were the best fruit God had created and I began to imagine young lively angels conspiring to plant a copy in the earth’s soil after they hear that Adam and Eve were being sent down here to earth as punishment. I plucked one off and it almost melted in my fingers. I threw it in my mouth and it dissolved, its small balls exploding like fireworks. I ate another and another. The nearby branches had begun to look barer when I started to feel dizzy. I touched the top of my head and it was as hot as a car’s hood at midday.

– p. 46-47

But as time goes by the dangers of the political system only multiply, and the world around Suleiman gradually worsens, getting more violent. His own father is beaten, his best friend’s father taken away. His mother listens to the boys in the neighborhood and cries out:

“Clouds,” she said. “Only clouds. What are you people thinking: a few students colonizing the university will make a dictatorship roll over? You saw what happened three years ago when those students dared to speak. They hanged them by their necks.”

– p. 52-53

The reference here—well-known to Libyans—was for the day when the traffic in Tripoli was routed through the city square so that all drivers would see the students’ bodies hanging from above. By the end of the first novel, the family has to emigrate to Egypt. Cairo is where Uncle Moosa lives, and there they take up a safe but spiritless expatriate life.

*

ANATOMY OF A DISAPPEARANCE (2011)

A novel. Explores the inner life

of a boy who is a teen when

his father has been

“disappeared”.

In this second novel we meet Nuri, a slightly older boy whose life trajectory has been seriously altered by the conditions of his expatriate father, and we see them at first living in Cairo. The father, spiritually distant, culturally aloof, hangs over the proceedings like a dark cloud. Nuri was closer to his uncle Talib than to his distant father, but his mother is sick. When his mother dies shortly afterward, cutting the familial ties with her side of the family, Nuri is left with Naima the housekeeper, and Mona, his father’s mistress, an Englishwoman.

One can sense a growing anxiety as the story unfolds. But still, everyday life proceeds with both humor and reverie. His uncle Fadhil visiting on one occasion from Libya:

For [Fadhil] the risk of retaliation for visiting his “backward traitor” relatives was greatest. He was oddly awkward and mostly sat smoking. Whenever I sat next to him he would squeeze my skinny upper arms and say, “Flex.” – p.53

Yet it was true: random “disappearances” still did happen. In time it became obvious something must be done to save the family. It is decided to send Nuri, who was intellectually gifted and who loved books, for schooling overseas. This boy thrust into the alien environment of boarding school goes on to meet other children of expatriates of other countries. A friend, Alexei, has a father who is an orchestra conductor who travelled the world widely.

So it is that Nuri’s life at his fourteenth year begins to resonate with fate and loss and aloneness, perhaps even dangerous doubts. His father’s mistress Mona stays in England, still with him, as much his companion as his mother-figure. Hankering for commonality, for heritage, for belonging, though, there is a despairing quality to Nuri’s observations.

Over time and by great distances, Nuri’s father schedules meetings and get-togethers at hotels in places like Geneva. One such time, at a meeting for the Christmas holidays in Montreux, his father does not show up. Some days elapse. Eventually, chilled with worry, Nuri and Mona learn of the father’s fate: they read in the newspaper that his father was kidnapped in Cairo and most likely returned to Libya for trial. Yes, in the newspaper.

From this tragedy comes a time for searching. His father had keenly drafted a will stating that “in the event of death or disappearance” the money was to be dispersed to Nuri and Mona. With every phone call, hope swelled in Nuri’s chest that his father might be found. His best friend Alexei leaves for Dusseldorf where the conductor has a year’s appointment. Reality closes in on Nuri, whose life becomes the loneliness of school combined with secret trips back to Cairo.

In the later chapters, Matar moves the needle of time ahead. As Nuri gets older and more adept at school, his private life becomes a series of meetings, hearing from acquaintances one or two bits of information about his father. He uses every scrap to create a picture for himself. Back in Cairo, Nuri always feels closer to home, even if somewhat desperate and longing for a connection.

I tried on more of his clothes. The tweed suit fit, albeit stiffly. When I pushed my arms forward I could feel the fabric stretch a little. Perhaps if I wear it often, I thought, it will gradually return to its original size.

– p. 223

*

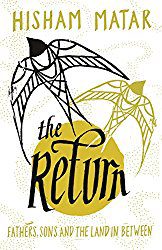

THE RETURN (2016)

A memoir. Explores the inner life

of the author himself

who returns to Libya

after the Arab Spring.

“The Return” is perhaps more of a meditation than a memoir. Everything in this book is sun-bleached by the events that come beforehand. But Hisham Matar’s arrival in 2012, and meetings with family and former friends are much more like the crest of a wave—beneath it the real story takes shape from within the mighty swell of flashbacks and hearsay and personal testaments to his father, most especially from former prisoners.

July 12, 2011. Two young men from Misrata, Marwan and Izzo, freedom fighters they breathlessly call themselves, careen to the top of a building in Zliten, replace the national flag with the flag of freedom—and by August both of them are dead in the fighting. A cousin of the author is found to be planning a Libyan Judge’s Organization to free the courts of political interference—whilst the Qaddafi government itself, under mounting pressure, was promising interest-free loans to students and an increase in foreign scholarships, all the while arresting every journalist, rights activist, and lawyer they could find.

This was in the days leading up to the chaos of the Arab Spring. In place of Suleiman and Nuri, we find Hisham Matar, the author himself, whose very presence stirs up old recollections. He is seeking out witnesses who knew something, knew anything, during what gradually becomes a frightfully, desperate homecoming. Hisham at first had hoped his father was still alive. Why not? Other prisoners had, in fact, survived.

Thus the specter of Jaballa Matar, who until now in these books we knew very little about, becomes the centerpiece of this search.

We still do not know that much about the person of Jaballa, at least not until much later in the book. But of his life and deeds we hear from friends and relatives, prisoners and co-conspirators, whatever Matar himself can piece together from the fragments of their memories. Jaballa had made good money importing Japanese and Western goods to the Middle East. He travelled widely, but always returned to Cairo where he ran his subversive organization. The money from his business helped fuel his activism, but he also raised money from wealthy expatriates much like himself. He set up a fund for Libyan students abroad. He managed and coordinated sleeper cells inside Libya. He established military training camps in Chad.

Then suddenly—in the early 1990s—Jaballa disappeared. Over time, his son Hisham withdrew from his own emotions.

I felt my heart contract and grow small. Pain shrinks the heart. You make a man disappear to silence him but also to narrow the minds of those left behind so to pervert their soul and limit their imagination.

– p. 213

It was widely assumed that in the 1990s Jaballa Matar was thrown in with the many thousands of political prisoners in the nightmarish Abu Salim prison. Hisham, on his return, found men who could testify to that. There, it seems, in dark and solitary cells, Jaballa wrote a few letters and managed to get them passed to the outside world. Many other prisoners knew him, not so much from interpersonal contact, as from hearing his voice, chanting in the dark, cavernous prison. What they could hear? It was Jaballa reciting poetry.

What made it possible to pass goods and information through the walls?

The architect had specified that the manufacturer punch a round hole at the dead center of each prefabricated wall. This way then the crane lifted the ready-made slab, it rose in perfect balance, as straight as a guillotine. The holes were then plastered over and concealed. But later, when the cells filled up, prisoners discovered their location. They found out that if they chipped away at the plaster, they could open a channel to the next cell, one big enough to pass a book through. Father describes these holes in his letter, then writes, “All sorts of goods pass this way. None are more precious than books. The prison is a great library.”

– p. 148

But there were only a few letters. The guards caught on to everything. They even feigned sympathy in order to steal goods from family members attempting to visit. In one case that Matar uncovered, a woman discovered that her son had actually died years before. Until then, however, on each visit she was told she could not see her son this time.

The guards seemed genuinely sorry. They promised to deliver her gifts and they never neglected to tell her to try again next month. Every month she cooked meals and purchased gifts for a dead son. The guards took it all for themselves, throwing away the letters and eating the food, and sold the other items to the inmates, or gifted them to friends or their own children.

– p. 216

There are life-affirming moments in the book, thank goodness. We learn from Matar’s researches that his father was a budding author as a youth, a story writer and poet. His grandfather was a patriot in the old sense, having joined the resistance against the Italians. Jaballa was known far and wide for his activism and his personal honor.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Qaddafi was feeling the pinch of world opinion turning against him, and he launched a charm offensive, primarily in the flesh and blood of his son Seif el_Islam. Within a few years the British and American governments were attempting to curry favor with the Libyan regime, for energy as well as geopolitical strategy. By 2004 Tony Blair had made overtures to Tripoli.

But Hisham Matar had a campaign of his own. He met secretly with Seif, testified and sat in on international hearings, met with the British foreign secretary David Miliband, and worked closely with Human Rights Watch to keep the pressure on western governments regarding the status of imprisoned and disappeared persons in Libya. The BBC World Service prepared a documentary on Jaballa Matar. Desmond Tutu contributed his own statement. There were results, of a sort.

But the world turned upside-down in December 2010 when a humble Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set fire to himself in Tunisia. Following that, the uprisings spread like wildfire throughout the Middle East.

EPILOG: A NEW LONGING FOR DESPOTIC RULE?

We didn’t know it then, but [the Arab Spring] was a precious window when justice, democracy and the rule of law were within reach. Soon, in the absence of a strong army and police force, armed groups would rule the day, seeking only to advance their power. Political factions would become entrenched, and amidst the squabble, foreign militias and governments would violently enter, seeing their opportunity. The dead would mount. Universities and schools would close. Hospitals would become only partially operative. The situation would get so grim that the unimaginable would happen: people would come to long for the days of Qaddafi.

—Hisham Matar, “The Return” p.123

Libyan Majdi el-Mangoush is [now a student] continuing his engineering studies [in Germany], but in contemplating the chaos engulfing his homeland, he has turned to a novel idea: a restoration of the monarchy that Qaddafi overthrew in 1969. “Not that it will solve all our problems,” Majdi told me, “but at least with the king, we were a nation.” Whatever happens in Libya, he is committed to staying and working for its improvement. “I am ready for a new kind of uncertainty,” he said.

—Scott Anderson, “Fractured Lands”, last paragraph

A Short history of 20th century Libya

The country was invaded by Italy in 1911. By 1922, after ten years of guerilla warfare, Mussolini ascended to his throne in Rome. Another ten years, and Italian battle fatigue led finally to a ruthless crackdown by General Rodolfo Graziani, who was helped in his cause by not a little mustard gas.

*

Eventually, on Sept. 11 1931, following twenty years of sustained guerrilla warfare, the noble Bedouin and Libyan folk hero Omar al-Mukhtar, then 73 years old, was wounded in a retreat on his horse and captured. After a show trial he was hanged on the outskirts of Benghazi—and, as was (and still is) the custom, thousands of onlookers were required to attend the ceremony. The war for independence was quashed.

*

Omar al-Mukhtar on the 10 Dinar Bill

*

Following World War II, Great Britain oversaw the country until 1952. Libyan rule was handed over to King Idris, who ruled over the oil fields until the Revolution of 1969. That’s the year Qaddafi and his military vanguard, under the banner of Arab independence, basically walked into the palace and just kind of took over in a bloodless coup.

Leave a Reply