Doppelgangers Make Strange Bedfellows

RECENT SUMMER sightINGS

Ever see yourself in a crowd? Not a video of yourself, but another person who looks just like you? Startling, riveting, definitely heart-stopping. You shudder to be reminded of how close you came to entering the world of . . . another dimension.

But then . . . nah. You tell yourself it’s all in the mind—perhaps it’s just the culture of superstition we live in. After all, vampires are now in vogue, the walking dead are back on the attack, demons and interplanetary creatures of every persuasion are, for all we know, hiding out in the backyards of suburbia.

So why not the doppelganger? Well, thankfully, sightings are still rare. Perhaps that’s because doppelgangers are different. They are not a race of creature, they have not invaded, they are not plotting to take over humanity, they don’t require our sucked blood to live.

In fact—and this may be the real problem—they are . . . us. Versions of us, actually. Or, more to the point, the other side of us. Herewith, a brief history, and following that, a survey of my recent summer sightings.

DOPPELGANGERS OF YORE

The aforementioned phenomenon has been haunting humanity since long before the Germans came up with a compound word for it.

In traditional folklore, doppelganger is a malicious and evil character having no shadow or reflection. It troubles and harms its counterpart by putting bad thoughts and ideas in his or her head. In some cultures, seeing one’s doppelganger is bad luck and is often a sign of serious illness or approaching death. — LiteraryDevices.net

But a century and a half ago, our cultural forebears began to turn this simple, provincial superstition into a literary industry. By the mid-19th century, a double was felt to be much more than another version of you. It was yourself turned inside out. It could mean double spirit, or, most endearingly, our evil counterpart—and the fact that the word doppelganger means “double walker” established its quasi-physical independence from us.

Wilson confronts (and mortally wounds) his double in an illustration by Arthur Rackham, circa 1935.

In novels and fiction, a double can be whatever an author has a mind for it to be. Washington Irving and numerous continental authors cashed in, and Edgar Allen Poe, ever the contrarian, even created a virtuous doppelganger in the story “William Wilson”—a look-alike who haunted the rakish William all his life with scrupulous scoldings. When finally William had had enough of his double’s incessant moral platitudes (whispering them, of all things), he one night discovers the hated double in a mirror image—and stabs him. By doing so, however, he has ended up killing himself. Well, that’s your Poe for you.

Generally speaking, your average doppelganger is quite the mischief-maker, and has always borne an existential question mark. If everyone else in the story appears to see him, then one must ask: is he, or is he not, flesh and blood? It has been said that Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” (1886) was a variation on doppelganger, but on that I disagree. For one thing doppelganger seems by definition to be independent and separate from the subject—not someone else he or she turns into. Still, Stevenson’s fondness for the split personality was typical of what I shall call the Doppelganger Era, for it was in the 19th century that this fascination with the evil twin erupted into many thrilling fantasies. People bought into it. Readers talked about it as if it could be true. Told stories about it as if they knew of a case. There was a thrilling willingness of belief behind it all—oh, and such audacious superstitions! It has been said that Abraham Lincoln saw his doppelganger just days before his assassination.

Thus a doppelganger sighting gives credence to the possibility that evil can be, at any time, embodied separately in our own image. Only then can we appreciate the mysterious lineage established by the earliest authors, duly inherited from them to us. In the revelations that follow, dearest reader, we seek the arc of doppelganger. Not as concept, not as an idea of the double, not as a vision of the sick mind as it moves through the landscape of modern literature. Rather, as it evolves into a living, breathing thing.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky “The Double” (1846)

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

The place? St. Petersburg, Russia. The era? 1840s. The style? Inscrutably unhinged. Nothing is as it seems. All that merely seems is doubtful. There is a backdrop of urban culture to the setting, an outward appearance of civility and calm, footmen and carriages, gas light and poker games. But roiling just beneath the surface of this story is a sense of foreboding that the author himself ladles up in great sloshing soup bowls of sardonic Russian humor. Oh yes, and absurd surnames.

The story is told through the embittered eyes and resentful mind of “our hero,” Yakov Petrovich Golyadkin—a short, middle-aged man for whom nothing ever goes right—a minor civil servant who has been oft-wronged, a resentful and solitary figure who senses that his life and work are overrun with fawning good-for-nothings out to get him. He lives in a modest walk-up, employs a servant named Petrushka who is lazy and refuses to say “sir” and who Golyadkin despises, and who despises him. He is ever searching for respect and never getting it, not even close—but what Golyadkin does get, in spades, is sneering and putdowns laced with scarcely-disguised sarcasm.

Near the beginning of the story he stops by to see his physician, Dr. Rutinspitz. He complains of melancholy. The uninterested doctor, clearly irritated, speaks dismissively. He advises Golyadkin to change his lifestyle.

“What I’m saying is that you must radically reform your whole life, and in a sense change your character completely. Go to theaters, go to a club, and in any case don’t be afraid of an occasional glass. It’s no use staying at home. You simply mustn’t.”

Privately Golyadkin thinks his doctor is a complete idiot, but argues his case anyway: his loneliness, he maintains, is actually his comfort zone. He claims to be nothing more than a natural-born homebody. “Peace is what I like, Doctor. Not the tumult of society.” But Golyadkin tends to get worked up. It is not long before the patient is off to the races:

“I have enemies, Doctor, I have enemies. I have deadly enemies who have sworn to ruin me . . . ,” replied Mr. Golyadkin in a fearful whisper.

Yet our Golyadkin plays at being a gentleman. Once he leaves the doctor’s office, he rides pompously around town in his carriage, bossing Petrushka, stopping here and there in the best parts of St. Petersburg, entering shop after shop, pretending to purchase expensive furniture and silverware, and leaving each store without actually handing over his minimum down payment. He even stops at a bank and cashes in his large bills for much smaller denominations, in an effort to impress with a swollen wallet.

Affectation and self-importance boil in his blood. Later that evening, he heads over to the house of Klara Olsufyevna, who is having a birthday party of Babylonian dimensions. Klara is the daughter of a Civil Counsellor but she is also secretly Golyadkin’s heart-throb. Many of the senior clerks have been invited. Golyadkin, uninvited, shows up anyway and is stopped, but manages to talk his way into the sumptuous festivities. And yet, as usual, Golyadkin makes a mess of things with his interminably self-important blather. At one point, he impetuously takes Klara’s hand just as the band strikes up a polka. Klara screams. Golyadkin is grabbed by the hands of several party-goers and summarily shown the door.

Outside snow is falling. Golyadkin walks home, muttering to himself about all the indecencies he suffers. Suddenly out of the darkness he is confronted by what appears to be an apparition.

As though struck by a thunderbolt, he stopped dead in his tracks, and spun round like a weather cock in the wind to stare after the man who had passed and was disappearing rapidly into the whirl of snow. He was dressed and muffled exactly like Mr. Golyadkin from head to feet.

Golyadkin frantically chases down the imposter. The double himself does not seem to notice the likeness, and summarily dismisses Golyadkin as a pestering hobo. How could this be? Golyadkin panics at first, and runs in the opposite direction. Then, exhausted and exasperated, he heads home.  He spies the double yet again, and this time follows him. To his own house. And there, he finds the doppelganger sitting comfortably on his own bed, ready to retire for the night.

He spies the double yet again, and this time follows him. To his own house. And there, he finds the doppelganger sitting comfortably on his own bed, ready to retire for the night.

The next morning the double is gone. Golyadkin putters late into work. In short order, a new employee is brought in, and takes the empty desk next to Golyadkin. Stunningly, it is the man he encountered the night before on the street. And what of the fellow employees? No one notices. How could no one else not see the likeness?

Not a soul would have undertaken to say who was the real Mr. Golyadkin, and who the counterfeit, who the old and who the new, who the original and who the copy.

Golyadkin peppers his fellow clerks with these questions, and even his own boss, but no one ever answers the real question with a real answer. All of which only serves to enrage Golyadkin, and in fact, unveils the genius of Dostoyevsky. Again our hero begins to think he might be going insane. But he counters his own fears by rationalization. How could anyone else not notice—unless they are . . . in league against him?

Golyadin begins to refer to himself as “Golyadkin Senior” and his double as “Golyadkin Junior”. He comes to the conclusion that perhaps an act of courtesy might be a peace-offering. Sr. invites Jr. over to his flat after hours. In due course, they drink five glasses of punch and get very drunk—and in the process, the much put-upon Golyadkin Sr. unloads his life story and his many regrets. Golyadkin Jr. merely scoffs at such indelicacies. The double appears to have no interest and no sympathies whatsoever. Worse, Jr. argues with Sr. incessantly. Eventually the double goes to sleep. And at that, Golyadkin Sr. immediately dissolves into a ragamuffin of regret, which, upon waking, he still is bothered by:

What a fool I am! I talked a string of nonsense when I meant to be cunning.

Back at work, Golyadkin’s double, is making headway into the sympathies of all the other workers, even so much as getting credit for all kinds of things. And it is not long before the double is working directly for the office manager Filippovich, and constantly bothering the original Golyadkin for all manner of irrelevant paperwork. No matter what Golyadkin does to assuage his imperious double, he is stopped at every turn and filled with anguish.

Golyadkin stops by a restaurant after work, exhausted and out of sorts. He orders a drink and a pastry. After a while, the waiter comes by and charges him for eleven pastries. “What’s happening to me?” Golyadkin asks himself. “If he says eleven, eleven it must be” he thought, turning a lobster red. The waiter insists that Golyadkin himself ordered the pastries. Golyadkin casts a glance across the room and suddenly spies Golyadkin Jr. in the midst of a party of friends. Jr. waves as if they were great friends. Sr. pays the excessive bill, and leaves the restaurant in a solitary funk.

As readers, we too begin to wonder: is this real? Or a dream? Rationalizations mount. It is clear our hero has been tricked by his double into all manner of outrages. As Golyadkin Jr. worms his way into the social circle of Klara Olsufyevna herself, a jealousy emerges. But then, one day, out of the blue, Golyadkin receives a note in the mail. The note is from Klara. She invites Golyadkin to assist her in a deception to quash an unwanted marriage. He is thrilled to be of assistance.

Until . . . well, I can only tell you the story ends at Klara’s house. The remainder of the sordid plot must not here be revealed.

*

The Upshot. So is Golyadkin going insane? Of course he is going insane, but Dostoyevsky’s point may be: wouldn’t we all? The internal monolog becomes the essence and lifeblood of the book. Even if Golyadkin is not an everyman, still, despite his orneriness, he certainly has our sympathies. Perhaps merely an eccentric, scorned by conventional society, our hero ends by being easily taken advantage of.

The Upshot. So is Golyadkin going insane? Of course he is going insane, but Dostoyevsky’s point may be: wouldn’t we all? The internal monolog becomes the essence and lifeblood of the book. Even if Golyadkin is not an everyman, still, despite his orneriness, he certainly has our sympathies. Perhaps merely an eccentric, scorned by conventional society, our hero ends by being easily taken advantage of.

The Legacy. Since Dostoyevsky, the doppelganger has a way of hanging around. You can’t shake him. Dostoyevsky placed the doppelganger in a completely realistic context—no mere sighting or haunting—more like a devilishly overlong visitation. Doubles are no longer fantasies, or simple apparitions. They are, in some strange way, with us—for better or worse.

The Twilight Zone “Mirror Image” (1960)

Millicent Barnes, age twenty-five, young woman waiting for a bus on a rainy November night. Not a very imaginative type is Miss Barnes, not given to undue anxiety or fears, or, for that matter, even the most temporal flights of fancy. Like most career women, she has a generic classification as a, quote, girl with a head on her shoulders, end of quote. All of which is mentioned now because, in just a moment, the head on Miss Barnes’ shoulders will be put to a test. Circumstances will assault her sense of reality and a chain of nightmares will put her sanity on a block. Millicent Barnes, who, in one minute, will wonder if she’s going mad.

— from Rod Serling’s opening narration

A rainy night—a tiny bus depot—a small town somewhere in the middle of nowhere—and poor Millicent (Vera Miles) has come down with a seriously bad case of disappearing luggage. Her misfortune is further complicated by a quixotically appearing doppelganger seen only in the mirror of the restroom. Of course the bathroom attendant can’t make hide nor hare of it. But Millicent can. Her luggage simply appears, then disappears. She can see the other woman perfectly—the double, dressed identically to herself—yes, right there, in the mirror—can’t you see? Ah, but once Millicent turns to look, the double has again vanished.

Add to this, the facts presented to the surly porter at the ticket booth are much ignored and scoffed at. And suffice it to say that Millicent is slowly losing her grip on reality. So much so that when the bus finally pulls in, she discovers to her horror that her double—yes, the same other woman she has been seeing all along—is already aboard the very bus she is waiting to take. Millicent gasps, then faints.

Poor Millicent. She manages to hang on for a short commercial break but that is only the beginning of the end for her. We watch as a handsome fellow traveler (Martin Milner) comes to her rescue. But this questionably “Good” Samaritan has the porter call the police of all things, and in no time it seems, our dear Millicent slides off the sanity cliff and is “taken away”.

So who is left? The fellow traveller. Suddenly alone in the bus station, and completely unaware that he too is stuck in the world of many selves, he settles in with some reading material . . . as you can imagine it is not long . . .within a few eerie seconds, actually . . . before his suitcase too . . . disappears.

The Upshot. It is not clear that Rod Serling intends to impart any particular interpretation on the proceedings. But he does offer a couple of options without specifically referring to a double. Says Serling at the close of the show:

Obscure metaphysical explanation to cover a phenomenon, reasons dredged out of the shadows to explain away that which cannot be explained. Call it parallel planes or just insanity. Whatever it is, you find it in the Twilight Zone.

— from Rod Serling’s closing remarks

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

HIGHLIGHTS . . .♦ Mirrors should be avoided

♦ Evaporating luggage is a slippery slope

♦ Parallel planes or just insanity?—but wait! Might not a doppelganger be afoot?

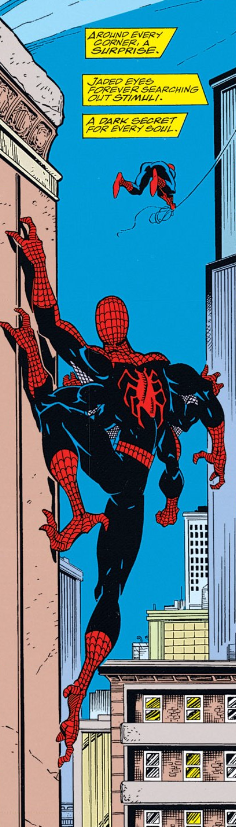

Marvel Comics “Infinity War #1” (2011)

Now the guys over at Marvel Comics have a different take on all this–as they are wont to do with all that time

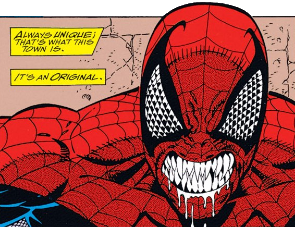

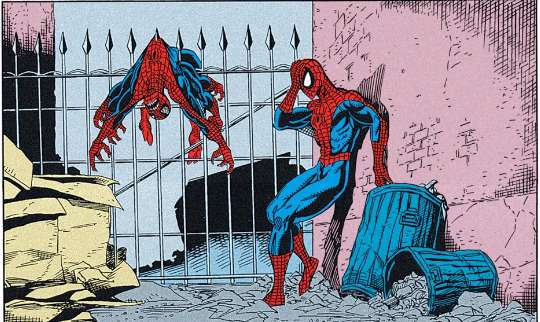

Now the guys over at Marvel Comics have a different take on all this–as they are wont to do with all that time on their hands. Whilst Peter Parker, aka Spider-Man, is merrily spinning his web from one tall city tower to another, just out of view lurks none other than his nearly–identical nemesis, Spider Doppelganger–waiting in the shadows, talons clenched on the outer wall of a lesser but clearly menacing building. The narrator intones: “A dark secret for every soul.”

on their hands. Whilst Peter Parker, aka Spider-Man, is merrily spinning his web from one tall city tower to another, just out of view lurks none other than his nearly–identical nemesis, Spider Doppelganger–waiting in the shadows, talons clenched on the outer wall of a lesser but clearly menacing building. The narrator intones: “A dark secret for every soul.”

But . . . talons? Well, sticking, as it were, to the theory that we need to fully embrace the doppelganger as our EVIL side, the fellas at Marvel saw a window. Specifically that he or she (or it, or whatever a doppelganger of a Superhero is) must be architected with a panoply of the most frightening hooked claws and drool-dripping sawteeth. Yes, you got it—a REALLY EVIL doppelganger! But this multi-clawed, somewhat lookalike double, this nightmarish knock-off with superhuman powers must—per the Laws of Anti-Hero Mechanics—have one fatal flaw: in this case, he is completely unintelligent and utterly animalistic.

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

♦ Doppelganger as sworn enemy?

—or—

♦ Doppelganger as force of nature?

Alas, before we know it more and more doppelgangers appear, a spate of them, more than you can count, seemingly one for every Superhero. But know this: our fearless Spider Doppelganger (whose occupation, by the way, is listed as “Predator” on the Marvel Comics website), cannot even come close to the cerebral dexterity of Spider-Man himself—who basically defeats his opponents with sly but clever variations on the same old entanglement. In the end, as always, Spider-Man gets a bit of a spanking, and is left with a fearsome headache.

The Upshot. We breathe a sigh of relief. Spider Doppelganger gets a worthy comeuppance right through the old abdominal cavity.

Jose Saramago “The Double” (2004)

The intentionally wordy but immensely popular Portuguese novelist Jose (pronounce the “J”) Saramago—yes, the same guy who won the Nobel Prize for  literature in 1998—wrote his own version of today’s theme, titled also, “The Double” (2004). Entendre or not, the book is another one of his patented 300+ page, non-stop, what I would call parable novels. Hey, this writer is a laureate. His subject is a doppelganger. The book beckoned.

literature in 1998—wrote his own version of today’s theme, titled also, “The Double” (2004). Entendre or not, the book is another one of his patented 300+ page, non-stop, what I would call parable novels. Hey, this writer is a laureate. His subject is a doppelganger. The book beckoned.

Tertuliano Maximo Afonso is a historian, a lecturer, and bored to the point of tears. He has virtually no friends, except his fiancée, Maria da Paz. His life has been reduced to teaching, grading papers, watching TV and videos, and occasionally taking in another few pages from a tome on medieval civilization that occupies a place of importance on his coffee table. But one night, after failing to find anything on TV and only half-heartedly considering a quick dive into medieval civilization, he pops in a video cassette The Race is to the Swift, a movie recommended to him by a colleague. To make a long story even longer, he spies a bellhop in a scene of the movie who looks–dare he rewind?—oh my, yes! . . . looks like—no, frighteningly IS—a dead ringer for himself with but one exception: a narrow, tasteful mustache. From which chapter we now cite a sample passage, Saramago-style:

Tertuliano Maximo Afonso got up from the chair, knelt down in front of the television, his face as close to the screen as he could get it and still be able to see, It’s me, he said, and once more he felt the hairs on his body stand on end, what he was seeing wasn’t true, it couldn’t be, any sensible person who happened to be there would say reassuringly, Come off it, Tertuliano, I mean, he’s got a mustache, and you’re clean shaven. Sensible people are like that, they tend to simplify everything, and then, but always too late, we witness their astonishment at the great diversity of life, they remember that mustaches and beards don’t have minds of their own, they grow and prosper only when allowed to do so, or occasionally, out of sheer indolence on the part of the wearer, but from one moment to the next, because the fashion changes or because their hirsute monotony becomes an irritating sight in the mirror, they can also vanish without a trace. —p.16

Huh? Well anyway Afonso feels compelled to contact this man, this actor, whose name is Antonio Claro. There are phone calls, letters, a long dance of discovery, and a fascination about each other.

Eventually they meet at Claro’s country home. Their voices sound exactly the same. They examine each other like two identical leopards meeting in the forest. Agreeing to take their clothes off, they also discover they are exactly alike, down to the toenail. Intending never to meet again, they part. But over time, the two doubles fall victim to their own fascinations. Things do get complicated. Like about 200 pages of complicated.

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

♦ Ganger and Doppel both as equal sparring partners

The two have the same birthday but naturally want to find out who is the original—who was born earlier in the day? Each becomes jealous of the other’s life and loves. Eventually they are undercutting each other’s intentions. Claro comes by Maria La Paz’ s address, follows her about. Claro then secretly confronts Afonso. Because he knows that Afonso has been less than truthful with him, and also with the suspicious Maria, he demands a devil’s ransom from Afonso: he promises not to divulge a thing, if he can spend one night with Maria, as if he were Afonso.

The two, not knowing exactly who is the original and who the double, begin the novel in a tango of existential fascination that at first features mustaches and fake beards, appearing and disappearing in Maria’s life, but gradually finding their appetites and passions for each other’s lives, crossing over to a dually-demented existence, ending in tragedy—if you can use that term for a tongue-in-cheek whopper of a story.

Saramago’s writing has a deliciously amused detachment, and comes with an eyebrow already arched and set. Some critics would say Saramago is a brilliant prose spellbinder, others might say a pleasant enough grammatical torturist. Some might say a motormouth of the spoken word, others a one-man literary-grunge-band. His books are not so much in the style of stream-of-consciousness as in never-ending flash-flood of parenthetical expressions. . . . and yet . . . .

The Upshot. No novella-ista, this Saramago. But clever as sin, nonetheless.

Denis Villeneuve “Enemy” (2014)

Far from being horrified by his doppelganger, Adam (Jake Gyllenhaal), a teacher, is completely fascinated. He really wants to get within a hair’s breath of Anthony (Jake Gyllenhaal), an actor—and that is what the movie “Enemy”, by turns, explores. Sound familiar?

Okay. So you already figured it out: “Enemy” is based on Saramago’s “The Double” and wrapped into a seriously myopic biopic. Or something along those lines.

You see, there’s nothing narratively new here. The names of the characters are about the only details that have changed from the book. But Adam’s fiancée Mary (Mélanie Laurent) is so much more woman than in the book. And so jealously suspicious. And it IS fun to watch the dueling doubles, if only for the fact that the movie takes itself much more seriously than Saramago’s wink-wink novel—whose author, to put it mildly, is far more interested in tedious digressions than characterization.

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

♦ Doppelganger, Ganger, and Ganger-Girl are hell-bent on desire and revenge

So while Villeneuve has nothing of Saramago’s lightness of being, our director and his scriptwriters, as well as the talented ensemble and the strangely passionless location, bring these passionate characters—jealous, resentful, power-hungry and frightened out of their wits— . . . to life.

A Mystery Clue

There is but one physical characteristic that Mary sees on Anthony which distinguishes the two doubles.

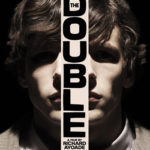

Richard Ayoade “The Double” (2013)

While “Enemy” (2014) plays out its Doppelgangerian mysteries in a relatively realistic and psychological context, the world of “The Double” (2013) is damn near the lunar opposite. Here, in what appears to be a bleak, northernmost, sunless industrial setting, life is as cold and dark and dank as the British producers could make it. The movie presents its tragicomic case in a dystopian, futuristic/mechanistic world of machines and meaningless work. What little we see of this world—through dimly lit grays and shadows—emanates everywhere as a kind of low-phosphorescent yellowish cast. The world of everyday Petersburg has become a foreboding blend of both futuristic and backward-looking Stalinist variations somewhat like a time-warped SteamPunk.

While “Enemy” (2014) plays out its Doppelgangerian mysteries in a relatively realistic and psychological context, the world of “The Double” (2013) is damn near the lunar opposite. Here, in what appears to be a bleak, northernmost, sunless industrial setting, life is as cold and dark and dank as the British producers could make it. The movie presents its tragicomic case in a dystopian, futuristic/mechanistic world of machines and meaningless work. What little we see of this world—through dimly lit grays and shadows—emanates everywhere as a kind of low-phosphorescent yellowish cast. The world of everyday Petersburg has become a foreboding blend of both futuristic and backward-looking Stalinist variations somewhat like a time-warped SteamPunk.

Our hero, Simon James (Jesse Eisenberg) is portrayed as an utterly and completely miserable dweeb, always on the verge of losing his job. Though he appears incapable of any self-determination, and lives as lonely a life as ever imagined, still, somehow, Eisenberg captures our sympathy. Bereft of confidence, and even possessed of a voyeur’s need for secrecy, he nevertheless holds one secret dear to his heart: a hopeless crush for one very pretty Hannah (Mia Wasikowska)—who for a while, unlike the distant Klara in the Dostoyevsky tale, takes a beneficent if ultimately uninterested pity on her hand-wringing suitor. Their boss, Mr. Papadopoulos (Wallace Shawn), is a demanding, mile-a-minute, browbeating cuss, but is nonetheless completely taken in by Simon James’s double, the suave, oppositely-named James Simon (Eisenberg), who shows up one day at work.

Again, as in the Russian tale, only poor Simon is aware of the switch. Maddeningly to Simon—but true to the genre’s Dostoyevskian form—no one else can see the resemblance. James, the intrusive Double, quickly and calculatingly becomes the boss’s favorite, moving up the ladder, pushing out the miserable Simon. James’ incessant cruelty and sadistic dismissiveness make for a satisfying agony whilst watching this melodrama.

HIGHLIGHTS . . .

HIGHLIGHTS . . .♦ Doppel as sexual predator/bully

♦ Ganger as whipped puppy/voyeur

Perhaps as expected, the movie introduces post-modern obsessions that Dostoyevsky would never have bothered with, let alone approved of: voyeurism and sex. The alienation, on the other hand—that would no doubt find old Fyodor much in approval. “The Double” is a wonderfully sinister take on the Dostoyevsky tale, hewing close to the cleverly warped spirit of the original. This is intense closet drama, under the expert eye of producer Michael Caine. No one does arch cruelty and condescension better than the British.

The Upshot. Doppelgangland has arrived. We have seen the enemy, and it is us. Dearest reader, take heed. No matter what time of day you choose to watch, prepare for a dark night of the soul.

visit: The Double (2013): Official Movie Trailer

One Fatal Final Factoid

“The Double” is rated R for “foul language and existential torment“.

Source summary

- “The Double” (1846) – a noir-novella, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

- “Mirror Image” (1960) – a haunting Twilight Zone 1st season knockout, written by Rod Serling

- “Infinity War #1” (2011) – Spider Man doubletakes on Spider Doppelganger, Marvel Comics

- “The Double” (2004) – an extremely verbose novel of a double intrigue, by Jose Saramago

- “Enemy” (2014) – a movie based on Saramago’s “The Double”, directed by Denis Villeneuve

- “The Double” (2013) – a movie based on Dostoevsky’s “The Double”, directed by Richard Ayoade

Leave a Reply