But Is It Poetry?

The Jarmusch Sensibility

Ah, movies! So many about art—so few about the actual making of it! I treasure Julie Taymor’s “Frida” (2002), a gorgeous biopic that dares take us into the passion, the pain, indeed the very wit and imagination, the hidden “art and soul” of the grand artiste Frida Kahlo—a rare thing indeed.

But passion, pain and suffering are not the currency of indie filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, so we pause here to explain: poetry or not, a Jarmusch movie is slow-cooked, offbeat, laidback—itself a love poem of extremes in everyday life. His movies are stunning to watch.

Decadent vampires with too much time on their hands.

His previous entry was the cult hit “Only Lovers Left Alive” (2013), a tale of two jaded, world-weary vampires (fear not: Tom Hiddleston plays Adam, a 400-year-old tormented musician cavorting with his vamping companion Eve, a lusciously pallid 3000-year-old Tilda Swinton). These two strut their wiles, and while away the midnight hours talking culture, sipping blood from wine glasses, making-out in a car in the worst neighborhoods of burned-out Detroit—(read: a culturally dead and burned-out America)—oh, and sharing near-stoned reveries of their many years of exploits over the centuries. Into this seemingly throwback swoon, though, is a visitation by Eve’s sister Ava, a wild-child, addicted to pleasure, whose unannounced visit inspires a rare murderous plot of absurdly comic proportions.

That’s Jarmusch. Clever, yes; visually astonishing, yes—but like all Jarmusch films nothing much happens for the most part. Still, who can forget the sharing of blood popsicles over a fiendly game of midnight chess?

Jim Jarmusch “Paterson” (2016)

Polka dots galore: Adam Driver and Golshifteh Farahan in “Paterson”

In what may be the only fictional movie that comes within a hair’s breadth of what actually inspires poetry—a rare film about verse with a dollop of magical realism—we are plopped down in the middle of an obscure life of an unknown poet.

The colorful window dressing persists in “Paterson,” but Jarmusch takes a leap forward into a somewhat more conventional setting, a sort of airy, everyday world just beneath the tedium of normal consciousness. Even so, it is no less achingly overstuffed with visual metaphor and cinematic eye-candy.

The film is about a poet. And the poet is a bus driver, and his name is Paterson, and he lives in Paterson, New Jersey—a town that glows with an “all-American” patina once lovingly applied by the real-life poet William Carlos Williams. Williams was himself the primo habitué of Paterson, New Jersey. In real life, his grand achievement was the five-volume epic poem, “Paterson” (1946-1958). But the poetry in the movie is not at all like that difficult poem. Paterson (the character) is himself a minimalist which is actually how Williams first made a name for himself.

The film is about a poet. And the poet is a bus driver, and his name is Paterson, and he lives in Paterson, New Jersey—a town that glows with an “all-American” patina once lovingly applied by the real-life poet William Carlos Williams. Williams was himself the primo habitué of Paterson, New Jersey. In real life, his grand achievement was the five-volume epic poem, “Paterson” (1946-1958). But the poetry in the movie is not at all like that difficult poem. Paterson (the character) is himself a minimalist which is actually how Williams first made a name for himself.

Paterson (the character) is quietly dismissive of modernism—the digital world in particular—and sort of rejects modernity. A smartphone is a leash, he says, and you could surmise correctly that Paterson is every bit the iconoclast, as is the writer-director who takes a jab at Instagram and Twitter, as if to say: I can’t buy into this new world of yours.

The movie spans seven days in Paterson’s life in an ethnically diverse “working class” part of town. Adam Driver plays Paterson, Golshifteh Farahan is his wife Laura. Each day and night is nearly the same, but with little changes, for this is a movie of slow-moving inspiration in the joy of the little things in life.

The movie spans seven days in Paterson’s life in an ethnically diverse “working class” part of town. Adam Driver plays Paterson, Golshifteh Farahan is his wife Laura. Each day and night is nearly the same, but with little changes, for this is a movie of slow-moving inspiration in the joy of the little things in life.

The out-of-doors is ringed in pastels, the indoors a plethora of pattern and color. Paterson, lunchbox always in hand, walks to work, boards the bus and each day, comes home after work with a couple more lines of verse in his notebook, straightens his mailbox. Laura spends her days decorating, painting a room, learning guitar, making cupcakes for a fundraiser, cooking dinner. Ostensibly they are lovers, but this is really symbolist theater we are watching. It seems a world of our dreams, these two lovebirds really more like two sides of the same creative force: Paterson the ploddingly thoughtful poet, Laura the spritely and unrealistic flower child, his inspiration.

And so pretty, pretty, pretty! The rotating overhead shots, the clutter of old things scattered about, the darkly dramatic conversations each night at the neighborhood bar. The characters gradually take on a depth that defies their humdrum existence. Worse still for discerning movie goers, they are uninterruptedly happy. Even Laura’s snotty bulldog has soft side to her gruff outer layer, a sort of lovable if irascible philosopher queen of the household.

And so pretty, pretty, pretty! The rotating overhead shots, the clutter of old things scattered about, the darkly dramatic conversations each night at the neighborhood bar. The characters gradually take on a depth that defies their humdrum existence. Worse still for discerning movie goers, they are uninterruptedly happy. Even Laura’s snotty bulldog has soft side to her gruff outer layer, a sort of lovable if irascible philosopher queen of the household.

What brings us here, though, is the poetry. In “Paterson” little snippets of three- and four- word ideas come now and then to our poet, arriving in slow, studied moments inspired by the tiny, little things and thoughts in his life: his wife’s polka-dot cupcakes, a thought about driving a bus and being surrounded by no more than molecules, a glimpse of an old-fashioned box of matches in the kitchen cabinet—flashbulb images of our sojourn through a normal life. These are then jotted into his notebook, a line here, another line there, in the spatial interstices between his duties as a bus driver. Eventually, over a few scenes, comes a poem.

What brings us here, though, is the poetry. In “Paterson” little snippets of three- and four- word ideas come now and then to our poet, arriving in slow, studied moments inspired by the tiny, little things and thoughts in his life: his wife’s polka-dot cupcakes, a thought about driving a bus and being surrounded by no more than molecules, a glimpse of an old-fashioned box of matches in the kitchen cabinet—flashbulb images of our sojourn through a normal life. These are then jotted into his notebook, a line here, another line there, in the spatial interstices between his duties as a bus driver. Eventually, over a few scenes, comes a poem.

The Run

I go through

trillions of molecules

that move aside

to make way for me

while on both sides

trillions more

stay where they are.

The windshield wiper blade

starts to squeak.

The rain has stopped.

I stop.

On the corner

a boy

in a yellow raincoat

holding his mother’s hand.

The lines of poetry appear on screen as he thinks of them, or rather, as his internal monolog speaks them—one word at a time, in ghostly handwritten white as if crafted by some fog light of sensibility. In the case of “The Run” (above) we see the city of Paterson, from inside the full front windows of the bus, flowing by in all its “molecules”. What emerges is the portrait of the artist as a working man, as he is first inspired, and then over time, as he builds on his inspiration to complete the piece.

Love Poem

… we discovered Ohio Blue Tip matches.

They are excellently packaged, sturdy

little boxes with dark and light blue and white labels

with words lettered in the shape of a megaphone,

as if to say even louder to the world,

“Here is the most beautiful match in the world…”

Padgett & Williams, THE POETS BEHIND THE POET

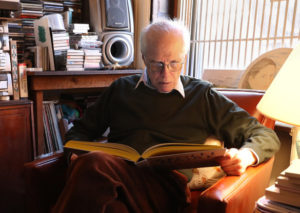

Poet Ron Padgett

As for the poetry itself, well, ta-da!

A fellow named Ron Padgett is the versifier-behind-the-curtain, the movie’s Wizard of Ozymandias. Unlike Paterson (the character), Ron Padgett (the real poet) is much older, roughly the same age as Bob Dylan. He was, and still is, quite the animated character and a friend of Jim Jarmusch. (Before studying film at Tisch, Jarmusch studied poetry at Columbia under Kenneth Koch. Ron Padgett did exactly the same, albeit one decade earlier.)

Though Padgett himself is not a household name, he is well-known in the poetry world for his avid and regular participation in the New York poetry scene, and a familiar name among what I call the plain-verse New York School poets. I say “plain-verse” not to imply one style or another, but to stress the minimalist approach that was common back in the 60’s and 70’s when Padgett was just getting started.

In a sense, his microscopically personal approach to poetic subject matter may have started with William Carlos Williams. A look back to Williams’ most famous poem of this style is likely this:

W.C. Williams

The Red Wheelbarrow

(1923)

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

The Williams’ phrase “no ideas but in things” is key to this approach. That quote appears early in the movie, lifted directly from “Paterson” (the epic poem). Let’s step back and peer at the ripples.

W.C. Williams

Paterson (1946)

—Say it, no ideas but in things—

nothing but the blank faces of the houses

and cylindrical trees

bent, forked by preconception and accident—

split, furrowed, creased, mottled, stained—

secret—into the body of the light!

William Carlos Williams 1921

Fittingly, many other references abound. Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems makes an appearance in the movie as well, and in recent interviews, Jarmusch has explained that one goal of the movie was to channel some elements of the New York School aesthetic, this cadre of American poets like Frank O’Hara and Kenneth Koch, who had this in common with Williams: an everyday sensibility about the nature of the world, along with a complementary satchel of insights using everyday parlance and “spoken language”— oh yeah, and the gall to be utterly Plain Jane about it.

W.C. Williams

This is Just to Say (1934)

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

So perhaps, if there is a kind of mysticism of the everyday, Ron Padgett made the cut. Most importantly, as has been pointed out, his political ambiguity suits us in these ungodly times. The momentary pleasures of this world are tiny, every day things.

But is it poetry?

People asked a similar question of Raymond Carver’s fiction, the perspective being one of everyday people rarely longing for more than a little relief from their problems. What’s cool is that Jarmusch gets this, and addresses the issue forthright. In a YouTube video “Paterson is an ode to making art from the details of everyday life”, NPR journalist Jeffrey Brown takes up the topic of “plain-spoken” poems in this interview with Jarmusch and Padgett first broadcast on PBS Newshour.

In an interview in “The Guardian,” Jarmusch says the New York School poets were his “aesthetic godfathers” and his philosophy is simple:

Make a poem to one other person, don’t make a poem to the world. Don’t take yourself too seriously. Allow humor. Their poems are very funny and have so much exuberance. Why shouldn’t poetry be that way? – Jim Jarmusch, in a recent Guardian interview

Jim Jarmusch

But that’s the film director talking. The real challenge for Jarmusch was how to portray the inspiration. He does so by landscape and by inference. The inner life of Paterson (the character) seems to be made visible by the colorful life of Laura. The famed city’s waterfall, the cupcakes, or the driver’s seat of a transit bus seem to be connected by patterns, by colors and by repetition everywhere. There are even twins showing up here and there throughout the movie, on street corners, at the bar, even on the bus.

Apparently William Carlos Williams was inspired by every little sparkle of life, such as a sparrow in a tree. On the other hand, Ron Padgett himself doesn’t provide much insight into inspiration. He writes his poems in the evening, he says, assuming it comes. Here is vintage Padgett, on the topic of what passes for inspiration.

I’ll watch a little bit of “Wheel of Fortune.” It’s a wonderfully predictable mindless show to watch, so it’s very soothing. And then after that I’ll work on a piece of writing, and then watch a bit of something else.

– Ron Padgett, in a recent “New York Times” interview

So if anyone can be accused of committing serious poetry here, perhaps it is writer-director Jarmusch whose “Paterson” (the movie) is a delight to watch, perhaps not so much if you’re into poetry, as into indie movies about poetry or literature. Of which, BTW, there aren’t that many—but in this vein I am reminded of another book and film, Muriel Barbery’s “The Elegance of the Hedgehog” (2006, film version 2009).

In a quirky, but admiring piece tartly titled “No Ideas But in Non-Digital Things” journalist Virginia Heffernan heaps praise on Padgett in particular.

Ron Padgett’s poetry in Paterson … sets a high-water mark for the representation of poetry in film. What’s more, Padgett’s simple lyrics are powerful tonic in an age of poltergeist Twitter dialect and sweetie-pie Instagram filters.

We might have to agree to disagree, but Jim Jarmusch makes it perfectly plain he doesn’t much care what we think.

We end in paradox. An inspiration is inexplicable, as illustrated by yet another piece by Ron Padgett, spoken by Adam Driver, but dreamed up by Paterson, our day-dreaming bus driver.

Another One

When you’re a child

you learn

there are three dimensions:

height, width, and depth.

Like a shoebox.

Then later you hear

there’s a fourth dimension:

time.

Hmm.

Then some say

there can be five, six, seven…

I knock off work,

have a beer

at the bar.

I look down at the glass

and feel glad.

Leave a Reply