But Is It Literature?

I remember as an undergrad having a book of poetry, one of Robert Creeley’s, which I had tried on several occasions to penetrate. One day when trying to work through the meanings, my mother, out of curiosity and genuinely wanting to know what was so interesting, inquired about it. So I read her a poem. She looked puzzled. She said awkwardly “Well, I could have written that!”

Now although I was quite used to her unfiltered approach to confronting the unknown, her comment secretly made sense. Because really, that is exactly what I had been thinking as well. How on earth is Creeley making these so utterly plain words on paper into a new kind of poetry?

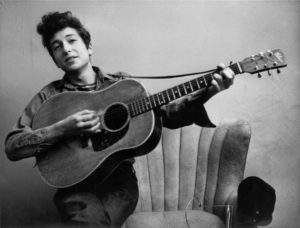

At that time poetry still struck a chord because we were reading and memorizing it in school. In second-year Latin, I turned in a translation of Ovid’s “Pyramus and Thisbe”. To me poetry was ethereal, a flight of the spirit, a good thing to have around. Like my mother, I wasn’t ready for Creeley’s poetry or Jackson Pollack’s paintings. If I had chosen to read her a few lines from a Bob Dylan song instead, she might have warmed. I say this because she also liked the Beatles of the “Norwegian Wood” phase.

Poetry was once a star above a very public planet. Poetry on the page was becoming a tiny window upon a personal inner world. In elementary and middle school, we were memorizing beloved poems. In my adult years, I used to wonder if something extraterrestrial happened between 1957 when Jack Kerouac read his hep-cat poetry on the Steve Allen TV show (intoned over the piano jazz licks of Steverino himself) and our late-century scene when poetry evolved into “readings” spoken reverently, mostly on university campuses.

Some people have suggested that poetry in the public sphere has simply disappeared. Others have proposed ever-newer theories of expression. Perhaps as a species of art, poetry has simply adapted, been selected for the newest branches on its ancestral art-tree: at the root there is bardic poetry … at the furthest reaches rock, rap, performance art and cinema.

The Bob Dylan Affair

When Bob Dylan was tapped as the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature last year, the announcement came as nothing less than a mind-blower. The times must be a-changin’.

The Nobel Committee—officially one of five committees in the “Swedish Academy”—is profoundly silent as to its annual, and equally inscrutable, intentions. The electors are mostly world-class professors, previous laureates, and presidents of various academies. The tradition is to keep it all very hush-hush. We are never privy to their thinking on any selection because (and here’s the kicker) the ruminations of said dignitaries are sealed for 50 years. The Nobel baseline is not much help either: (1) you must be living, and (2) your stuff must be really, really good.

The Academy provides one tiny tea leaf to read, but no more. That is to say, for each laureate the committee releases a one-line declaration of why the pick was made. It usually starts with the word “for” as in the case of Dylan:

For having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition

Recognizing the need for a little more clarity following the worldwide outburst of disbelief, Sara Danius, the Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, added her own special polish to the aforesaid. Dylan, she announced, was a “great poet in the English tradition… a great sound poet…”

The Swedish Academy

Suddenly it’s lead balloon season. Maybe this is why the academy is mostly silent because when they try to make sense of it, they kind of “English” it up. What’s worse, the designation sound poet actually means something else entirely. Could such an utterance be the Academy’s way of diverting attention away from controversy? If so, it seems to have backfired.

Yet another attempt at intellectual clarification surfaced:

Dylan is the brilliant inheritor of the bardic tradition.

– Salmon Rushdie

A well-meaning sentiment. Perhaps a bit of justification from on high. But “Inheritor”? Really? Is that what makes a Nobel laureate?

They’ve been giving out the prize for literature since 1901. Nowadays recipients get a stipend of million dollars as well. In 1907 the prize was for the first time awarded to a beloved poet, Rudyard Kipling. Old Kip was writing in an era that not only prized poetry, but actually read it.

Soon after Kipling, however, modernity forced its way into the Nobel cathedral. The turnstile to immortality appeared to be blocked to poets of popular appeal. In fact, looking over the list, I see only a few other poets who had a certain popular following: (1) Seamus Heaney, who is certainly world class and at least close to popular among even the literati, and (2) a few others like Toni Morrison or Herman Hesse who just happened to be poets who wrote great novels.

Over the years I’ve heard a few poets recite. If any of those had a chance to win a Nobel, I’d have to wonder about one: Allen Ginsberg, whose pedigree was not only hip but fairly historic and form-shattering. Ginsberg’s early poems were Jeremiads, and really more like prose, but dear old Allen may have ruined his chances with the Academy by morphing into a Hindu guru—and staying that way for decades. From the back of the auditorium in Chapel Hill I craned my neck just to catch a glimpse of him: draped in a dhoti and sitting on stage in a faux lotus position, he held a mic in one hand and stroked his “bardic” beard with the other. What I heard, though, was mostly chant. Was that poetry? Was Ginsburg the “inheritor” of some ancient tradition?

I must say among my favorite recitations was one by Galway Kinnell. I witnessed this bear of a man recite his muscular verse back in the 80’s over at Emory University to an overflow crowd—and I hesitate to say “recite” because Kinnell did not so much read his poetry as blast it from memory, hands tucked behind his back, pouring forth a freight train of words and off-rhymes—a kind of solo rock concert, declarative as hell, and in a rhythm unlike any other.

Some singer-songwriters like Leonard Cohen, who died recently, were often likened unto great poets too. So it was with Joni Mitchell and Neil Young. In my class on Literary Criticism, we hotly debated whether Cohen’s immensely popular “Suzanne” (1972) was a pop song or a poem. No surprise that our teacher railed against the idea of songs being poetry, vociferously and passionately. Also no surprise that the students all took him on.

The big surprise with Dylan was not so much that an honor was bestowed (he has received many others), but that the academic establishment picked him. Some ideologues outside the mainstream hoped that he would decline the honor (Sartre did). Some were of the opinion that others were more deserving, whatever that means. In 1953, in an age of great speechifying, the Nobel Prize for Literature went to Winston Churchill—for his bracing, classically-inspired oratory. But even back then, the question had to be asked: Was it literature?

The big surprise with Dylan was not so much that an honor was bestowed (he has received many others), but that the academic establishment picked him. Some ideologues outside the mainstream hoped that he would decline the honor (Sartre did). Some were of the opinion that others were more deserving, whatever that means. In 1953, in an age of great speechifying, the Nobel Prize for Literature went to Winston Churchill—for his bracing, classically-inspired oratory. But even back then, the question had to be asked: Was it literature?

Does Dylan fit any mold? He may just be so inimitable that he’s deserving. In a culture where song is almost always verse-verse-chorus, the “bardic” Dylan hearkens back to the seer, and the folk-singer mode of verse-verse-verse-verse-ad infinitum. In a culture where song rhymes are often forced by cliché, Dylan attacks with a forge of words and street slang unlike any other—the words may well be commonplace but are never cheap, bent around the vernacular in a way that is fresh and surprising and a starkly perfect pitch each time.

That’s where I think the explanations offered so far by the Nobel Committee and Danius and Rushdie miss the boat—while leaning to the academic, they overlook the raucous street-smart excitement, and thus, the real poetry, of Dylan’s work. Apart from the narrative bliss of his stories and his settings, the rhymes alone are amazing—phrase-rhymes, off rhymes, rhymes-on-rhymes—captivating but captured in the whirl of the catchphrase. The fact that he never stops for a breath is no less amazing—and always ending each aching line with a word held for at least the length of a whole note.

Dare we view the songs as poetry on the page? Let us cite but a handful of the multitude.

Subterranean Homesick Blues

(1963)

Johnny’s in the basement

Mixing up the medicine

I’m on the pavement

Thinking about the government

The man in the trench coat

Badge out, laid off

Says he’s got a bad cough

Wants to get it paid off

Like A Rolling Stone

(1965)

You used to laugh about

Everybody that was hangin’ out

Now you don’t talk so loud

Now you don’t seem so proud

About having to be scrounging

for your next meal.

Love minus Zero/No Limit

(1965)

In the dime stores and bus stations

People talk of situations

Read books, repeat quotations

Draw conclusions on the wall

Hurricane

(1975)

Now all the criminals in their coats and their ties

Are free to drink martinis and watch the sun rise

While Rubin sits like Buddha in a ten-foot cell

An innocent man in a living hell. ….

Bello and Bradley and they both baldly lied

And the newspapers, they all went along for the ride …

Couldn’t help but make me feel ashamed

to live in a land where justice is a game.

Dylan at 76. Still touring, still playing, still writing, still growling it out.

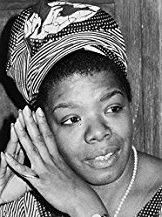

But can protest verse be lit? Open Langston Hughes—read “Let America Be America Again” (1938). Take some time with Alan Ginsberg’s “Howl” (1956). Listen to a recording of Maya Angelou recite “Caged Bird” (1983). Dylan’s stuff may or may not be capital-L lit, but it’s the same great sword of saintly revolt, the common wail and cry of the human spirit, the long dagger of dissent. Alas, it requires justification because … it’s popular.

Bob Dylan—an intemperate, high-minded scold with an aching, scratchy Victrola voice—can come across as an ingrate if you don’t see things in his terms. It took him months to formally thank the Academy, for which some in the ranks have felt spurned. But that’s Dylan, playing with his back to the audience—he is our living legend, but reluctantly so. His 40-album output is unchallenged, but still he clings to the shadows. As did Joni Mitchell, Dylan offers only his sung lyrics, a counter narrative to the idea that poetry is defunct.

So if you want to engage, first check out how poets have themselves responded—for the most part welcoming. The consensus seems to be that Dylan is so unique, so old-fashioned rhythmic, so colorfully activist, how could he not be deserving? No question that poetry still pulses in the culture, but who now is shaking us alive? Who now reminds us that some kinds of non-page-only poetry are, in fact, literature?

Maya Angelou on Bob Dylan (2011)

Maya Angelou

Performance art was the stock-in-trade of this one-time ingenue, who was, in her long life, very “unbardic.” A dancer, actor, memoirist, speaker and poet, Angelou was no less a voice for the beaten and downtrodden than Dylan, one difference being that Angelou wrote poems that were to be shouted from the mountaintop, verse that she virtually sang.

And yet her song-like lyrics drew great admiration: her repeating refrains … her powerful social message … her shared vision of overcoming obstacles—all so very much like, and sounding not unlike, Bob Dylan himself, as in this:

Maya Angelou

The Caged Bird

(1983)

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

In 2012, Maya Angelou and Bob Dylan both received the Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. In fact, Angelou’s own reminiscence of Dylan may be the best summarization of his significance to our world.

There was a time when Bob Dylan was the young kid on the block. We all sang at the Purple Onion and the Hungry I and at folk-music clubs. When Bob came along, everyone loved him because he was what we all had meant to be; he spoke for all of us. And he was known to be honest, which is what a great American artist is. It may not be expedient, but the audience can trust the artist who is honest, and Bob Dylan followed what he said in his lyrics by his actions. He supported the human being, the spirit of being an American — of knowing that the mountains and the rivulets and the voting booths belong to all of us, all the time.

– Maya Angelou in 2011

Bob Dylan “Nobel Lecture in Literature” (2017)

I wanted to write songs like nobody had ever heard. – Bob Dylan, “Nobel Lecture”

A few weeks ago on June 4, Dylan recorded a stunning, elegantly unvarnished “Nobel Lecture in Literature” in Los Angeles. He managed to get it to the Academy just under the wire, one day before deadline. For his efforts, he qualified for that cool million.

Of course, as with everything Dylan, you must listen to the lecture. He tosses in all his influences, he sifts his literary faves in Dylan-speak, he stirs in the great books he learned in school, he spices it up with Buddy Holly and Lead Belly and even John Donne. The great works, he savors, but oddly favors the epic. He dives headlong into “Moby Dick.” He hails “The Odyssey.” He tramps through the killing fields of “All Quiet on the Western Front,” recalling the painful and disquieting scenes.

In this rare glimpse into the inner life, Dylan seems to live and breathe the themes of the great stories. In them, he serves up a montage of great characters who represent the struggles of us all. He is the quintessential bard of freedom. He is ours.

By the end of the lecture Dylan turns humble and philosophical. He feels a muse working its magic through him. He confesses that his lyrics resonate with cultural, humanistic, and yes, even Biblical, references. His songs are imbued with the stories of his youth and our human predicament.

Still we feel the irony: Is it literature?

In the last paragraph he turns rhetorically to his audience at the Swedish Academy. He seems to want it both ways:

Our songs are alive in the land of the living. But songs are unlike literature. They’re meant to be sung, not read. The words in Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be acted on the stage. Just as lyrics in songs are meant to be sung, not read on a page. And I hope some of you get the chance to listen to these lyrics the way they were intended to be heard: in concert or on record or however people are listening to songs these days. I return once again to Homer, who says, “Sing in me, oh Muse, and through me tell the story.”

Ah, Dylan … “gently lecturing” the lecturers … and why not? It’s a one-take gig. He is still our generation’s Yoda, speaking in riddles and paradox. Here he flings out the obvious (that songs are meant to be sung), then he ends by putting his name alongside Homer and Shakespeare.

Hard to argue now that Dylan has made it to Mount Olympus. But does that alone make him a poet? Let’s hear from his own work once more—where he sings of a poem that was written in his soul.

Tangled Up in Blue

(1975)

She lit a burner on the stove

And offered me a pipe

“I thought you’d never say hello,” she said

“You look like the silent type”

Then she opened up a book of poems

And handed it to me

Written by an Italian poet

From the thirteenth century

And every one of them words rang true

And glowed like burnin’ coal

Pourin’ off of every page like

it was written in my soul … from me to you …

Tangled up in blue …

If someone had ever told me that I had the slightest chance of winning the Nobel Prize, I would have to think that I’d have about the same odds as standing on the moon.

– Bob Dylan

Leave a Reply