Behind Miles Ahead

jazz fusion: Miles Ago

. . . the albums . . .

- Weather Report 1971

- Return to Forever 1972

- Head Hunters 1973

- Mahavishnu Orchestra 1971

- Staircase 1976

. . . and the headliners . . .

- Wayne Shorter

- Chick Corea

- Herbie Hancock

- John McLaughlin

- Keith Jarrett

. . . and all called something like . . .

- Jazz/Rock

- Jazz/Funk

- Jazz/Fusion

These were the music and albums I cut my jazz teeth on. Not the only ones, but I actually saw some of those guys in Buffalo and elsewhere in concert back in the day. Thrilling. Something I wanted to be a part of.

One day recently, and not entirely out of the blue, I picked up Miles Davis’ “In a Silent Way” (1969)—a strange combination of jazz horns and rock rhythms driven by Tony Williams’ manic drum shuffle—a band not quite there, but pushing forward into the unknown association with rock.

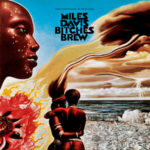

I listen twice through. I read the tiny liner notes. Then all becomes revealed. Every frickin’ one of those guys I mention at the top played with Miles Davis in the 1960’s—and Davis, who also had his own fusion breakout, “Bitches Brew” (1970)—was always itching for new material and innovative approaches—kind of led the pack.

I listen twice through. I read the tiny liner notes. Then all becomes revealed. Every frickin’ one of those guys I mention at the top played with Miles Davis in the 1960’s—and Davis, who also had his own fusion breakout, “Bitches Brew” (1970)—was always itching for new material and innovative approaches—kind of led the pack.

Fusion was huge. And sacrilegious. A lot of jazz devotees were befuddled. Davis himself credits the influence of Jimi Hendrix. “You can’t stand still,” Davis was fond of opining. No sense of me going into material that has been discussed many times, but this leads to two thoughts this beautiful Sunday morning: (1) memories of a new and youthful and exciting colorful world of music opening out before me, and behind me, (2) the dark clouds of a history of music I had not known before. Both worlds of airy bliss would, over time, eventually part, and allow me into their secrets.

Don Cheadle “Miles Ahead” (2016)

But if you actually listen to Miles Davis—the musician—over all his years—the early, mature, late—especially to an ear as untrained as mine—you may not agree with me, but I find the same dude always singly exploring the spaces in whatever musical environment he presently inhabits. Yes, true, he always liked new ideas, new technologies, new forms, new expressions—but that same old horn player is always there, tipping his hat from the mountaintop, blessing us with his bluesy jazz lines, and slipping out before you know it in the shadows behind the curtains.

But then there’s Miles Davis the man—immersed in a sea of hurt and anger and addiction—leading to his utter unpredictability and the inevitable chaos of his life. His musicians often complained of his walking off stage in the middle of a performance. His near-paranoia of the music industry sharks, his understandable distrust of white people, are legendary.

But then there’s Miles Davis the man—immersed in a sea of hurt and anger and addiction—leading to his utter unpredictability and the inevitable chaos of his life. His musicians often complained of his walking off stage in the middle of a performance. His near-paranoia of the music industry sharks, his understandable distrust of white people, are legendary.

These two flip sides of Miles Davis collide like galaxies in Don Cheadle’s movie “Miles Ahead” (2016). The intensity of his playing drew on this deep well of unrest, and his uncontrollable passions often threw his career into a careening mess. Was this something he had in common with Vincent van Gogh?—topic for another day . . . .

That movie just opened this month, and I was waiting to pounce. I had put in a request with Fandango for the automated email. Dang, Fandango! When will it hit Atlanta? I mean, jeez, it just opened in New York at the first of the month—where the hell is it?

Finally that email arrived last Tuesday. Movie was due in the ATL on Friday, first showing at Tara Theater, 2pm. I immediately arranged to take Friday afternoon off. Connie and I weren’t the first to settle in our seats, I can tell you that.

Cheadle’s long-awaited, crowd-funded, un-biopic takes us into two very dark and lonely places: the successful, imperious, complicated and misunderstood Miles Davis of the late 1950’s and the nearly-psychotic down-and-outer of the late 1970’s. We are tossed violently and unmercifully back and forth between the two worlds, and in the end left with a man who does make a comeback, and does it on his own fuckin’ terms, mutha-fucka—as he himself would say.

The plot is a mess, but so is life. A present danger hovers—Miles having a mix tape stolen in the late 70’s—and keeps jolting us back to the past. It is crazy, but not unlike jazz, you just let it happen to you—though I must admit the Dolby surround sound helps a lot. It is wonderful and transforming, the movie and its music, and Don Cheadle—himself a bit of eccentricity rolled into one tight body—does a masterfully impossible embodiment of both ends of Miles’ personality. He also wrote and directed the film. He even learned trumpet.

Don Cheadle as Miles Davis

It is one of the best pictures I’ve seen in years—but bear in mind—the critics—the oh-so-hepcat critics—while praising Cheadle—are crapping all over the film for the intrusion of a made-up story line. For shame, critics. You miss the theater of it. A once-in-a-lifetime drama about a near-psychotic genius always on the very edge of out-of-control but somehow managing to hang on within the lines. This is an impressionist effort. It cinematically mimics the man’s style as much as his talent. Here we get only the high points and reverberations of his life. Here we get the music and we get the man—and his marvelous wife and his amazing musicians. You get the anger and the drugs and the paranoia and the forbidden fruit. It is all very real.

Davis the genius lived on a planet of his own. His music—especially that from the late 50’s—was out of this world. He loved music and musicians—that is where he lived, when he could. But he was flawed in ways that worked for and against him. He wrote an autobiography that is almost unreadable if you don’t care to know everyone he ever played with, how they played, what they said, and so forth.

Connie and I once saw Miles Davis “live in concert” in late summer of 1990 with his “DooWop” group. It was the end of a long night of a Jazz Fest at the outdoor Lakewood Amphitheater, and Connie was tired, pregnant with Kyle at the time—but we, and the crowd, breathed a sigh of relief when the man appeared on stage after what seemed like an hour late. ’twas worth it, of course. A little over a year later, Miles Davis died of just about everything you could die of. He was 65.

I recommend the movie to any Miles Davis fan. Better than any Davis book I’ve ever looked at. The books are overload. The movie is pinpoint. Can you wrap a genius into a movie? It’s been tried many times, and many times has come up short. But yes. Yes you can. Right now I am listening to the seminal album “Kind of Blue” (1959). But I wonder if Miles isn’t somewhere walking off stage as I write.

Leave a Reply