Our Refugees, Our Enemies

Refugees is a “term” we now live with daily. It could be defined as those fleeing persecution, or worse: drought, famine, poverty, war. I’m not sure we have a name for those who don’t make it out; perhaps left-behind is a good as any. Clearly they are really two sides of the same coin.

Two years ago this month, our country observed a polarizing and awkward event: the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. For the most part it was a muted celebration. There were, of course, the obligatory news stories, some candlelight vigils, but no real pomp and circumstance. Some Americans were not yet ready; some were returning to visit. Many of us watched the riveting documentary “The Last Days of Vietnam” (2014) on the PBS series “American Experience.”

Some would say these were our refugees. In those final, agonizing days and hours of April, 1975, the communists of the North at long last commandeered the suburbs of the South. News cameras captured Russian-made tanks rolling into Saigon. A flurry of unreal sights caught the world’s attention: the takeover of the Presidential Palace, the mad crush of civilians fleeing the city, a view of rocket-pocked runways bereft of the promised, waiting airplanes.

Some would say these were our refugees. In those final, agonizing days and hours of April, 1975, the communists of the North at long last commandeered the suburbs of the South. News cameras captured Russian-made tanks rolling into Saigon. A flurry of unreal sights caught the world’s attention: the takeover of the Presidential Palace, the mad crush of civilians fleeing the city, a view of rocket-pocked runways bereft of the promised, waiting airplanes.

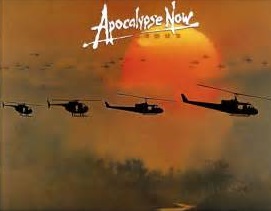

Sitting at home in front of our televisions, we watched over several days as U.S. forces fled the scene. The lasting image may be that of helicopters valiantly but haphazardly airlifting families from rooftops—transporting the lucky few to aircraft carriers waiting at sea.

Cameras were at too safe a distance to capture the many personal agonies that were unfolding, almost by the second—stray bullets, senseless violence, the resulting chaos a sobering testament to the inability of the American forces to evacuate even a fraction of those who would soon be slated for re-education camps, or worse. Of the “boat people” picked up at sea, most were delivered to the U.S. base at Guam where, in tent cities, the agonizingly slow process of applying for passage to America was just beginning.

That we as a people really don’t know much about the people we were fighting for is by now an understatement. That we as a people still know next to nothing about our enemies’ war experience is also a truism.

But the Vietnamese, both North and South, they remember. In books, in family and oral histories, in old newspaper articles and documentaries, in the shared culture of the many “Little Saigons” everywhere, a heartbeat stirs: the personal stories of the old who never adjust, the young who suffer alienation, and those in the middle—who, once young, still awkwardly stand between two worlds.

Last year the slowly disappearing memory of Vietnam was loudly pierced by a Pulitzer Prize, awarded to author Viet Thanh Nguyen for an astonishing novel I had completely overlooked at the time, “The Sympathizer” (2015). This year, I devoured his next offering, “The Refugees” (2017). Over the last twelve months, I dipped into other Southeast Asian authors that seemed to hold promise, and found Bao Ninh’s “The Sorrow of War” (1990). Things haven’t been the same since.

Viet Thanh Nguyen “The Refugees” (2016)

Viet Thanh Nguyen (pronounced Viet Taan When)

We begin with Nguyen’s latest book, “The Refugees,” which was assembled from twenty years of the author’s published and unpublished short stories.

It is an inviting introduction to the real people—some struggling, some falling from grace, some salt of the earth—as they embrace and cope with the great shadows of a former life. Here in America they encounter hostilities, the loss of heritage, fear of a mysterious new culture, and bring with them the paradox of Catholicism combined with ancient Confucian belief. In this collection we fall in not just with our refugees of the past, but a new generation peeling off from the diaspora of somewhat hidden lives in the United States.

“The Other Man”

Memories of the last days of the war hang heavy over the story of young Liem whose memories of the final days haunt him incessantly.

Although he hadn’t planned on kicking, shoving, and clawing his way aboard a river barge, he found himself doing so one morning after he saw a black cloud of smoke over the airport, burning on the horizon, lit up by enemy shellfire. A month later he was in Camp Pendleton waiting for sponsorship.

Having succeeded in saving himself, he spends long days in the tent city at San Diego.

As he lay on his cot and listened to children playing hide-and-seek in the alleys between the tents, he tried to forget the people who had clutched at the air as they fell into the river, some knocked down in the scramble, others shot in the back by desperate soldiers clearing a way for their own escape. He tried to forget what he’d discovered, how little other lives mattered to him when his own was at stake.

Liem is tortured but hopeful of rebirth. Eventually he is sponsored by a gay businessman from San Francisco. The man’s young partner Marcus eventually, and inevitably perhaps, becomes Liem’s unwanted suitor. In many of these stories, the inner life of the refugee is suffused with a subtle but poisonous mix of forced gratitude and remorse, but here there is a crippling sensation of social inferiority.

“War Years”

We wade into the midst of a family fissure taking place at a mom-and-pop grocery located in the comfortable confines of the Little Saigon Market in San Jose “where English was hardly ever spoken and Vietnamese was loud.” Our narrator is 13 years old, and while it is his job to place price tags on all the cans of fish sauce and star anise and red chilies, it is his nature to observe.

We wade into the midst of a family fissure taking place at a mom-and-pop grocery located in the comfortable confines of the Little Saigon Market in San Jose “where English was hardly ever spoken and Vietnamese was loud.” Our narrator is 13 years old, and while it is his job to place price tags on all the cans of fish sauce and star anise and red chilies, it is his nature to observe.

The owners are in the crosshairs of a well-known local personage, a certain Mrs. Hoa whose goal in life is to shake down community businessmen for contributions to a guerilla army of anti-communist soldiers training in the jungles of Thailand. Mrs. Hoa snakes into the store and meets the owners at the cash register.

“I struggle to make ends meet too.” Mrs. Hoa unclasped and clasped the silver latch on her purse. … “But people talk. Did you hear about Mrs. Binh? People say she’s a Communist sympathizer, and all because she’s too cheap to give me anything. There’s even talk of boycotting her store.”

Our grocery mom is fed up, infuriated at the extortion. Her husband is of the mind to simply pay the “hush money” and get on with life. They argue about the communists. These parents saved their minuscule profits for themselves, sending some scraps of profit back to the old country. The father’s brother, still in Vietnam, writes there is no money for auto parts at his parts store. Says the mother: “I hate the Communists as much as Mrs. Hoa, but she’s fighting a war that can’t be won.”

Of course, the persistent Mrs. Hoa revisits the store time and again. As a last resort she loudly proclaims to all within earshot:

“You heard her didn’t you? She doesn’t support the cause. If she’s not a Communist, she’s just as bad as a communist. If you shop here, you’ll be helping the Communists.”

“The Transplant”

A man named Arturo grants a Vietnamese refugee the use of his carport because the refugee’s father has saved his life through a blood transfusion. But the goods in the carport are all counterfeit. At first Arturo refuses the offer of a 10% take. But Arturo is broke, a gambler who whose body is failing, has jaundice, marriage gone to seed, etc. And now he has no choice but to cut a rotten deal with the likes of a crass Vietnamese broker.

“I’d Love You to Want Me”

An old professor, unable as a refugee to get a job in his specialty as an oceanographer, takes to teaching Vietnamese to “Heritage Learners” for which there is almost no market. His memories cloud his judgment, his place in the world has been humbly diminished. Ticking against the clock of a meaningful resolution is his creeping dementia.

“Someone Else Beside You”

A strict, old-world father—divorced, old-fashioned, perennially unhappy—confronts the failures of his life and, at least for a time, must go to live with his Americanized son—where, needless to say, things do not go well.

“Fatherland”

A young, successful American woman of Vietnamese descent visits the present-day Vietnam, and is distrustfully regarded, a puzzle to her relatives who eventually discover she is lying about her success, as she is but a part-time worker back in the U.S., and currently out of work.

“The American”

Here we find not just the sly Vietnamese soul willing to play by multiple rule books, but an insight into role reversal caused by a horrid war of long ago. James Carver, an American, and his wife of Japanese descent, Michiko, have come to Quang Tri to visit their daughter Claire, once a youthful idealist, now an accomplished rural English teacher. Carver is a 60-something former U.S. pilot who once flew bombing missions in Vietnam. Claire’s boyfriend Khoi is working on a grant from the D.O.D. to provide a robotic solution for defusing landmines (“demining” they call it), a project that a cynic might regard as a 21st century band-aid for a 20th century epidemic.

Gradually, as Carver becomes reacquainted with the surroundings, as he grows more intimate with Claire, as he raps with Khoi and the young man’s villager-assistants, the former pilot instinctively recoils time and again. To seeming slights, he reacts fitfully and unpredictably. He feels betrayed and poisoned by the naive good works of his daughter. At the wisp of a bitter memory, he feels himself falling into a swill of despair.

Outrage and self-pity propelled his every step. He had never explained to Claire the difficulty of precision bombing, aiming from forty thousand feet at targets the size of football fields, like dropping golf balls into a coffee cup from the roof of a house. The tonnage fell far behind his B-52 after its release, and so he had never seen his own payload explode or even drop, although he watched other planes of his squadron scattering their black seed into the wind, leaving him to imagine what he would later see on film, the bombs exploding, footfalls of an invisible giant stomping the earth.

Bao Ninh “The Sorrow of War: A Novel of North Vietnam” (1990)

Bao Ninh in 2006

Bao Ninh, himself a survivor of eight long years in the jungle during the conflict, has delivered our battlefield enemy’s contribution to the canon. This book burst onto the scene in the early 1990’s thanks to the British who translated it long before official publication was allowed in Vietnam.

In the novel’s opening scene, we come upon the dark jungle of the Central Highlands in the years following the end of the war. Kien, a soldier, is cataloging and locating the remains of his fallen comrades. He has been reassigned to this MIA Team (Missing in Action—Remains-Gathering), and we find him lapsing into memories both pleasant and painful, such as evenings with his fellow soldiers playing cards and smoking rosa canina root, a local anesthetic, as it were, used both to sustain and to numb.

With canina one smoked to forget the daily hell of the soldier’s life, smoked to forget hunger and suffering. Also to forget death. And totally, but totally, to forget tomorrow. -p.12

This is a war novel that kind of defies its own categorization, told as a reverie that haunts the narrator Kien all the days of his life. We drift in and out of his life: as a teenager when he fell in love; as a soldier when he killed many others; as a writer when he strove to put it all together, in a strange and disconnected perspective.

The author was a member of the Glorious 27th Youth Brigade, which itself was utterly defeated in battle in 1969 and became known as the “Lost Battalion.” Over 500 young men were wiped out in a matter of hours, and but a handful—ten—survived. Thus Kien too knows this spot well. This ghostly locale became a symbol of the revolution and has ever since been referred to as the Jungle of Screaming Souls.

That was the dry season when the sun burned harshly, the wind blew fiercely, and the enemy sent napalm spraying through the jungle and a sea of fire enveloped them, spreading like the fires of hell. Troops in the fragmented companies tried to regroup, only to be blown out of their shelters again as they went mad, became disoriented, and threw themselves into nets of bullets, dying in the flaming inferno. Above them the helicopters flew at treetop height and shot them almost one by one, the blood spreading out, spraying from their backs, flowing like red mud.

The sobbing whispers were heard deep in the jungle at night, the howls carried on the wind. Perhaps they really were the voices of the wandering souls of dead soldiers. Kien was told that passing this area at night one could hear birds crying like human beings. They never flew, they only cried among the branches. And nowhere else in these Central Highlands could one find bamboo shoots of such a horrible color, with infected welts like bleeding pieces of meat. – p.6

Kien as cataloger also acts as our witness to the many ghosts, voices, apparitions in the dense, dark forest that still cry out, voices that seem not to have fled their earthly bonds.

Time in this novel flows both ways. There are no chapters, only segments and narrative breaks, but Ninh’s style—which imparts an endless quality and an unrelenting persistence of memory to the narrative—is combined with the author’s penchant for heart-wrenching detail. Now and again we go back to a special time and place, before the American escalation in 1965. And in those early years in Hanoi, Kien had a love affair with a beautiful girl named Phuong. But the Youth Union members denounced them with the fervor of their communist precepts.

Time in this novel flows both ways. There are no chapters, only segments and narrative breaks, but Ninh’s style—which imparts an endless quality and an unrelenting persistence of memory to the narrative—is combined with the author’s penchant for heart-wrenching detail. Now and again we go back to a special time and place, before the American escalation in 1965. And in those early years in Hanoi, Kien had a love affair with a beautiful girl named Phuong. But the Youth Union members denounced them with the fervor of their communist precepts.

There were frenzied campaigns championing the “Three Alerts” and “Three Responsibilities” and the harshest, the “Three Don’ts,” which forbade sex, love or marriage among young people. – p.131

The intensity of the affair fills Kien with aching, and as we move through the book more and more details are revealed like a dream expanding and contracting with each new development. Oddly, as bittersweet and agonizing as the memories are, this one love affair seems to sustain Kien in his darkest hours, and nourishes his need to feel real, and alive, in opposition to the great sadnesses he has witnessed.

Kien’s memory, which acts as the Everyman of this novel, puts him also squarely in the Thanh Hoa train station in May, 1965, during one of the most horrifying bombings known to the Vietnamese.

Everything that could burn was burning. From the capsized train, men, women, and children rushed onto the platform to escape. Clothes caught fire and burned on their bodies. Headless shadows stamped about. The roar of the planes continued unabated, with bombs falling obliquely in the sunlight. -p.119

Of course the bombing of Hanoi and the north continued for years. What the U.S. Generals termed “Operation Rolling Thunder”—a campaign intended to cut off supply lines to the south, and damage the morale of the Viet Cong—accomplished the opposite. The more soldiers the North lost, the more they supplied. In true guerrilla fashion their troops would retreat during a bombing mission, and forge ahead during the intervals.

As happens in these books, April, 1975, stands out as a particularly horrifying day to Kien, especially the days of the 29th and 30th, the very last days of the war, when irrationally but intractably the young were still dying at each other’s hands. Though in this case there were no Americans left, the gunfire was chaotic and the fight was purely the Viet Cong vs. the “Saigonese” who proved themselves fierce warriors to the bitter end.

In those last days, Kien is assigned to the airport. He witnesses not anything like the joyful celebrations seen later on newsreels. To Kien the scene—the drunkenness and violence, literally “a barbarian world”—was awash in both death and sudden freedom. At the furthest end of his memories, he nearly lost his own humanity.

He began to have nightmares about the naked girl they’d dressed up. … her chest white, her hair messy, her dark eyes swarming with ants, and on her lips a terrible twisted smile. … this was a human being who had been killed and humiliated, someone even he had looked down on.

The remainder of the book draws upon all these disparate memories, and fashions them into a touching, if at times horribly ugly, story. After the cessation of hostilities, while the Vietnamese felt relieved, many were lost and many mournful of their former culture which had been ripped apart. The economy in postwar Vietnam was ruined; the country still divided.

Hanoi was not like his jungle dreams. The streets revealed an unbroken, monotonous sorrow and suffering. … There was a shared loneliness in poverty. Another idea flashed into his mind by a written sign: “Leave this place! Leave!” He began dreaming again of returning to Doi Mo, where someone had promised to be waiting for him. The orchard at the rear of Mother Lanh’s house, the view across the stream to the forest, the peace of the rural scenes. – p.151

In 2006, when President Bush visited Hanoi, the author was interviewed by visiting journalists, among them The Guardian. His novel is testament to the dignity of those who died, and a monument to their purity before the storm. So you’ll know: Bao Ninh is still living in Hanoi, never left Vietnam, and never published another book.

Viet Thanh Nguyen “The Sympathizer” (2015)

Nguyen himself was 4 years old in April of 1975 when his family was suddenly plucked from their South Vietnamese life and replanted in a camp for refugees in Pennsylvania. Nguyen is an insightful student of history. He has taught English and American and Ethnic Studies at the University of Southern California for 20 years now, all the while quietly devoting his creative energy to fictional accounts of the refugee experience. In this, his first novel, he has created a first-person antihero the likes of which we rarely see in American writing.

Nguyen himself was 4 years old in April of 1975 when his family was suddenly plucked from their South Vietnamese life and replanted in a camp for refugees in Pennsylvania. Nguyen is an insightful student of history. He has taught English and American and Ethnic Studies at the University of Southern California for 20 years now, all the while quietly devoting his creative energy to fictional accounts of the refugee experience. In this, his first novel, he has created a first-person antihero the likes of which we rarely see in American writing.

I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds. I am not some misunderstood mutant from a comic book or a horror movie, although some have treated me as such. I am simply able to see any issue from both sides. Sometimes I flatter myself that this is a talent … – Chap. 1

As is typical of this genre, the storyteller remains unnamed throughout. In voice, I was reminded of the snarky Oskar Matzerath in Gunter Grass’s “The Tin Drum” (1959); others have pointed to a more salient precursor, the well-drawn and unnamed narrator of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” (1952). Perhaps it is not a stretch to feel the presence of the darkly comic/psychotic narrator of Dostoyevsky’s “Notes from Underground” (1864)—all of these phantom personages are admittedly highly unreliable, but each of them sort of an Everyman as well—each of them, to a tee, surgically correct in their unconventional perceptions.

The book opens in the final days of the Vietnam war, as chaos is raining down upon a despondent South Vietnamese General for whom our narrator works—as driver, as officer, as attaché, as Captain, and (unbeknownst to anyone, even his best friend Ban) as a mole for the communist North. But he (from here on, I shall simply call him “the sympathizer”) is also a Eurasian—a half-breed, in his own words, a bastard—the very predicament of so many other Southeast Asians in this time of war.

It was not [the French] who invented the Eurasian. That claim belongs to the English in India, who also found it impossible not to nibble on dark chocolate. Like those pith-helmeted Anglos, the American Expeditionary Forces in the Pacific could not resist the temptations of the locals. They, too, fabricated a portmanteau word to describe my kind, the Amerasian. Although a misnomer when applied to me, I could hardly blame Americans for mistaking me as one of their own, since a small nation could be founded from the tropical offspring of the American GI. This stood for Government Issue, which is also what the Amerasians are. – Chap. 2

Our sympathizer is not without a plenitude of opinions, many of which concern the identity of both himself and his countrymen. This contrasts sharply with the view of their overseers, the American military, and even that of the typical Vietnam narrative.

In other words, what we see here is the desperate voice of survival in a world of unreason, a man purposely without allegiances, an informer and a survivor. And what we witness are unexpected and absurd terrors woven into eye-opening scenes of the evacuation not elsewhere reported.

So the gloves are off. The opening narrative veers right and left as if we were riding along in a crazed Saigon taxi. The sympathizer has hidden ties to Hanoi, and equally hidden ties to the CIA—both of which ensure him carte blanche to pass around large sums of money. In the privacy of the halls of power, money is exchanged for all manner of largesse. In the final hours fleeing civilians are shot in the back by the South Vietnamese army. In the evacuations on the tarmac we huddle with the bleeding and fleeing hordes, who by the way are made up mostly of the wealthy, all manner of bribe-paying citizens, prostitutes favored by the sergeants, even spies like himself.

In essence: we have been invited into perception from below, the experiences of the oppressed, the crushed spirit of the powerless who must sell out to the powerful, in a withering storm of surviving, tattered and torn patriotism that, in the end, can come and go either way. In short, we live the fate of the refugee.

After Guam we arrive in San Diego and refugee camp life from which our sympathizer writes letters to his “aunt” back in Vietnam, what are carefully coded dispatches in the duty of his espionage. His General is heading up a plot to lead an insurgency from the jungles of Thailand, but hears there is a spy in his midst and requests that his counsel, in the body of our sympathizer, look into it. The sympathizer, afraid that he will be found out, fingers a lowly major, and then with Ban, his longtime friend from the old country, sets out to “take care” of this falsely accused former major, this stand-in stooge, with cold vengeance and hardly a wisp of conscience.

I wanted to persuade the General that the major was no spy, but it would hardly do to disinfect him of the idea with which I had infected him in the first place. … Not doing something was not an option, as the General’s demeanor made clear to me …. He deserves it, the General said, disagreeably obsessed with the indelible stain of guilt he saw stamped on the major’s forehead. … But take your time, I’m in no rush. – Chap. 6

Gradually the General and the sympathizer come into contact with an ultra-right-wing congressman whose nickname was Napalm Ned:

He was so anti-red in his politics he might as well have been green, one reason he was one of the few politicians in Southern California to greet the refugees with open arms. The majority of Americans regarded us with ambivalence if not outright distaste, we being living reminders of their stinging defeat. We threatened the sanctity and symmetry of a white and black America whose yin and yang racial politics left no room for any other color, particularly that of pathetic little yellow-skinned people pickpocketing the American purse. – Chap. 7

Over time, as this new and authoritative voice evolves, yet another sympathy emerges that makes it possible for the sympathizer himself to attempt, now and then, to empathize. In this way Nguyen brings to life the ambivalence and the dashed hope of the refugee. Freedom is contingent on so many things.

I kept my tone upbeat about life in Los Angeles. Perhaps unknown censors were reading the refugee mail, looking for dejected, angry refugees who could not or would not dream the American Dream. I was careful, then, to present myself as just another immigrant, glad to be in the land where the pursuit of happiness was guaranteed in writing, which, when one comes to think about it, is not such a great deal. Now a guarantee of happiness—that’s a great deal. But a guarantee to be allowed to pursue the jackpot of happiness? Merely an opportunity to buy a lottery ticket. – Chap. 9

After the war, well, the war rumbled on. The Military Vietnam became the Hollywood Vietnam. We no longer exported our propaganda via speeches and the movement of aircraft carriers, but rather via the “Platoon” strategy—movies that delivered an American hero with an antiwar message. Movies, however, that continued to ignore the Vietnamese victims. Indeed, one of the best sections of the book is when the sympathizer is eventually hired by the stuffy director of “The Hamlet” (a dead ringer for Francis Ford Coppola and “Apocalypse Now”, btw) to breathe some bit of life into the native characters of that movie.

After the war, well, the war rumbled on. The Military Vietnam became the Hollywood Vietnam. We no longer exported our propaganda via speeches and the movement of aircraft carriers, but rather via the “Platoon” strategy—movies that delivered an American hero with an antiwar message. Movies, however, that continued to ignore the Vietnamese victims. Indeed, one of the best sections of the book is when the sympathizer is eventually hired by the stuffy director of “The Hamlet” (a dead ringer for Francis Ford Coppola and “Apocalypse Now”, btw) to breathe some bit of life into the native characters of that movie.

The real world, though, doesn’t breathe life. It turns out refugee camps. There were as many then, in the months following April of 1975, as there are today: camps for the Vietnamese all over the world, in Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Hong Kong—swollen with refugees from war and poverty and drought and slavery.

And as our ever-evolving sympathizer heads out to recruit Vietnam extras for the movie, he pauses to meditate.

I had seen refugees before, the war having rendered millions of the southern people homeless within their own country, but this mess of humanity was a new kind of species. It was so unique the Western media had given it a new name, the boat people, an epithet one might think referred to a newly discovered tribe of the Amazon River or a mysterious, extinguished prehistoric population whose only surviving trace was the watercraft. These boat people were either runaways from home or orphaned by their country. In either case, they looked bad and smelled a little worse: hair mangy, skin crusty, lips chapped, various glands swollen, collectively reeking like a fishing trawler manned by landlubbers with unsteady digestive tracts. They were too hungry to turn up their noses at the wages I was mandated to offer, a dollar a day, their desperation measured by the fact that not one haggled for a better wage. I had never imagined the day when one of my countrymen would not haggle, but these boat people clearly understood that the law of supply and demand was not on their side. What truly brought my spirits down, however, was when I asked one of the extras, a lawyer of aristocratic appearance, if the condition in our homeland were as bad as rumored. Let’s put it this way, she said. Before the communists won, foreigners were victimizing and terrorizing and humiliating us. Now our own people are victimizing and terrorizing and humiliating us. I suppose that’s improvement. – Chap. 9

2 Responses to “Our Refugees, Our Enemies”

I read The Sympathizer while viewing the PBS Vietnam Documentary–after hearing about the book from this blog’s author. The Sympathizer reminds me of Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison. This is first rate extraordinarily high quality literature! I will be reading the other books discussed here.

It is truly insightful. As for “Invisible Man” I mention, but do not explore, Ellison’s influence on Nguyen. I would love to hear in what ways you see parallels.