Esteban in His Own Words

His name was Esteban, and he was a rare breed for sure: a black Moroccan slave who lived 500 years ago, celebrated for his exploits alongside Spanish explorers in the Americas. That he also survived a disastrous voyage and became a gifted interpreter and trailblazer—all that contributes to his street cred even now.

He came to the New World in 1527 on the Narváez expedition, a mission intended to further colonize northern Mexico and seek out new land for conquest. At this point in his life, he was not on anyone’s radar, essentially a nobody, just another slave among the eighty on that expedition.

Esteban’s master was Andrés Dorantes, a stern Spanish nobleman and captain of the Gracia de Dios. His ship was one of four caravels sailing on the final leg of the undertaking, with soldiers, conquistadors and colonists aboard. The expedition departed from Seville nine months earlier and by February 1528 was headed due west out of Cuba in the direction of present-day Tampico, Mexico.

The journey was never expected to be a cinch, but during the crossing from Spain to the Caribbean it was plagued with adversity. There were desertions after docking in Santo Domingo. There was the loss of two ships from a hurricane in Trinidad with 60 men killed and one-fifth of the horses drowned. Even after reestablishing the fleet and wintering in Cuba, they set sail again only to run aground on an archipelago at low tide. Finally sailing west, they missed a resupply stop in Havana due to bad seas.

You would think things could not get any worse, but soon after leaving the island of Cuba they encountered winter winds and rugged currents preventing them from tacking westward. In those days they didn’t really understand the Gulf Stream but were keenly aware of running out of time and food. And so after four weeks of knocking their heads against the forces of nature, the stubborn Narváez signaled for a change of direction.

You would think things could not get any worse, but soon after leaving the island of Cuba they encountered winter winds and rugged currents preventing them from tacking westward. In those days they didn’t really understand the Gulf Stream but were keenly aware of running out of time and food. And so after four weeks of knocking their heads against the forces of nature, the stubborn Narváez signaled for a change of direction.

Narváez was the Governor of the expedition and, as such, he alone made the final decisions. He did not, as others might have done, reverse course. Instead, he turned northward, his sights now trained on La Florida, a land with a baleful reputation. There would have been no confusion among soldiers, passengers or crew about the upshot of this course correction: engagement with the Indians was virtually guaranteed. For in that fabled land with (as yet) no established Spanish military presence, Portuguese slavers prowled the shores with the sole purpose to profit by capturing and enslaving unsuspecting natives. The Indians were primed and ready for any and all trespassers.

The initial approach brought them close to present-day Sarasota, and from there the navigators headed cautiously northward, up the western side of the peninsula. The lookouts aboard ship scanned for signs of indigenous settlement. Eventually a small fishing village was sighted. The ships weighed anchor, and the wary adventurers climbed into their boats, in teams, descending to the waves below and rowing ashore. The colonists were to remain aboard ship and await further instructions.

ESTEBAN: THE BACKSTORY

Esteban was originally not Esteban. He was an obscure North African man with no known ties to any family or community. Of this earlier life, we know only that he came from Azemmour, a town on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, about 50 miles southwest of Casablanca. As for his origins, that is all we know. We don’t even have his real name.

As a slave in the Spanish empire, he would have been forced to “give consent” to convert to Catholicism, be baptized, and receive his new “Christian name”—Esteban, Steven in English. From that point on, his full legal name was Esteban de Dorantes, linking him to his owner. We should add that his contemporaries often called him Estebanico, Little Steven—the diminutive “ico” being applied to slaves just as it was for children.

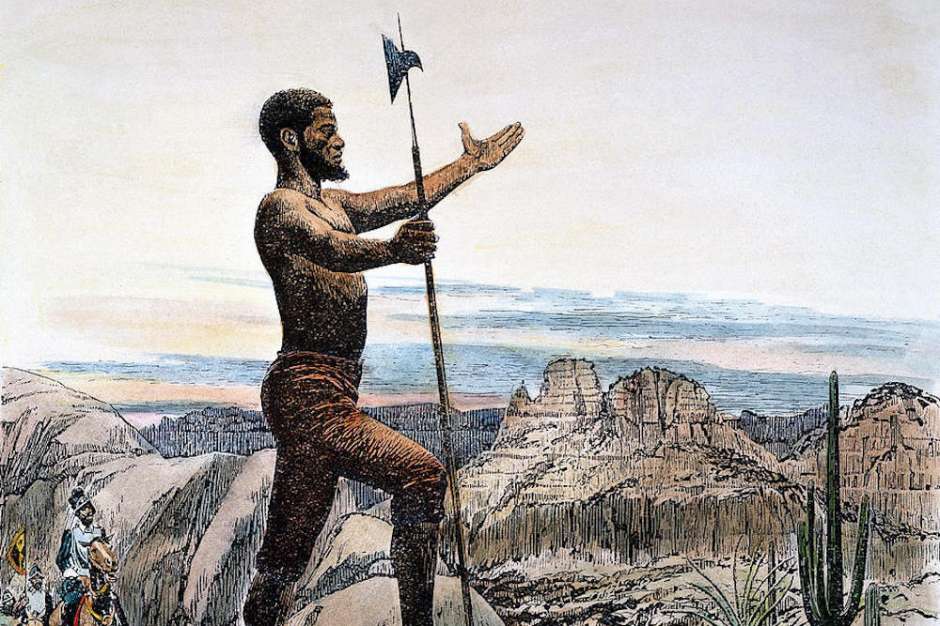

The Narváez expedition was, quite simply, an unmitigated disaster. There were only four survivors out of some 300 explorers who set foot on land, and Esteban was one of those four. After an eight-year ordeal submitting to, and travelling among, Indian tribes, the four men eventually made it safely to Mexico City in 1536, and by that time Esteban was a somebody. He caught the attention of the Viceroy of Mexico, and a year later was assigned the job of lead guide on an exploratory expedition to discover the Seven Cities of Gold. It was on that second trip in 1538-39 that he earned his reputation. His story appeals now as classic saga of the mighty contributions of a lowly personage, just as in the movies.

Idealized bronze-Tampa, FL

The problem with Esteban is that we esteem the explorer but know so little about the inner man. With the survivors and other principal characters, historians can consult letters and documents and contemporary portraits. With “the slave,” on the other hand, the primary sources only describe his actions. Other than skin color we have no clue what he looked like. We do not hear or read what he might have said, or how he might have said it. If there are any quotes or writings from him, I haven’t found one.

We do know that for his endeavors he was highly regarded, but we yearn for particulars. Historians today do what they can to resurrect him in the flesh, scouring source material for clues regarding Esteban’s “possible” past, his “probable” intentions, or the “likely” skills or even doubts that he “must have” possessed. Mostly we learn the details of the expedition, and the stories of survival. The heart and soul of this individual still fall into the shadows.

For now, since the story of Esteban cannot be separated from the story of the Narváez expedition, we imagine Esteban walking cautiously alongside Dorantes, who would have been on horseback, slogging through the mangrove swamps and backwaters of this alien landscape. We shall return to him soon enough, but first we must hear a little more about the fate of the explorers, their route, and, if you will, the utter routing of their number.

Cabeza de Vaca

“Account of the Narváez Expedition” (1543)

In our day, the word “ill-fated” might easily be inserted into the title of this book. Published by Penguin and still available, the author’s “Account” is as gripping now as it was in its day.

Cabeza de Vaca was second-in-command, a skilled warrior, first and foremost, but he was also well-educated, an engaging writer and sympathetic explorer. For all his accomplishments he was in one way significantly different: he never seems to have resented the Indians’ will to fight and to survive, as did so many other conquistadors who had to engage them in battle. His sympathies show through.

Cabeza de Vaca was second-in-command, a skilled warrior, first and foremost, but he was also well-educated, an engaging writer and sympathetic explorer. For all his accomplishments he was in one way significantly different: he never seems to have resented the Indians’ will to fight and to survive, as did so many other conquistadors who had to engage them in battle. His sympathies show through.

Pánfilo de Narváez, on the other hand, was a decorated commander with an outsized ego and a checkered history, much renowned for his vicious treatment of the Indians in Cuba. He was no deal-maker. Here in Florida the Indians were hostile and deceptive to a degree rarely encountered by the Spanish back on the islands. Indeed, by the time of this expedition, even the legendary Ponce de Léon himself had gone down fighting near present-day Charlotte Harbor, Florida, dying in 1521 from a poison arrow wound in his leg.

Pánfilo de Narváez, on the other hand, was a decorated commander with an outsized ego and a checkered history, much renowned for his vicious treatment of the Indians in Cuba. He was no deal-maker. Here in Florida the Indians were hostile and deceptive to a degree rarely encountered by the Spanish back on the islands. Indeed, by the time of this expedition, even the legendary Ponce de Léon himself had gone down fighting near present-day Charlotte Harbor, Florida, dying in 1521 from a poison arrow wound in his leg.

Before long one of the men found “a golden rattle among the fishnets” and, in another village, “traces of gold.” From that point on, there was no stopping Narváez. Out of nowhere came this do-or-die mission to locate the source of the gold. And for that alone, the men would have to march northward. The colonists would just have to wait.

To press forward, Narváez devised a cockeyed scheme to separate the ships from the landing party. He himself would lead a contingent of 300 soldiers on foot and horseback, in search of gold, while the ships would head north to a “great bay” that his navigator had promised would be there. Only after the gold had been found would the colonists be able to rendezvous with the foot soldiers.

EVERGLADES AND SWAMPS

The Indians were adept at a primitive version of guerrilla warfare, attacking and then disappearing into the dense marshes and everglades—a watery nightmare that must have seemed to the Spanish like an underworld dystopia. Many of the Spanish could not swim, a fact that did not go unnoticed by the Indians as the invaders forded many a river. Surprise skirmishes were the norm. While the conquistadors were attempting to load, prime and fire their harquebus rifles, the Indians’ armor-piercing arrows whistled out of nowhere.

Indians crept up unseen and fell upon our rear. A boy belonging to a nobleman named Avellaneda, who was in the rear guard, sounded the alarm. Avellaneda turned back to assist, and the Indians hit him with an arrow on the edge of the cuirass [the chest plate coupled with back plate], piercing his neck almost completely through, so that he died on the spot, and we carried him to Aute. … There we found that all the people had left and the lodges were burned, but there was plenty of corn, squash, and beans, all nearly ripe and ready for harvest.

— Cabeza de Vaca, “Account,” Chapter 7

When the Spanish entered a village, they seized all the available food even if it was still ripening in the fields. Usually the Indians had evacuated just prior to invasion, but before they left, they burned their own huts. At night they would counterattack and take hostages, as did the Spanish.

When captive Indians were tortured, Narváez would ask them: where is this great city of gold? And the Indians would always say: “Apalache.” The Spanish assumed that discovering Apalache was something akin to finding the city of Tenochtitlán, the renowned Aztec capital. Yet when finally Narváez made it to Apalache, there was no gold, no great city, just another village, a little bigger than the others.

Scouts routinely returned to the coast to look for the ships with the colonists, but neither ships nor bay were ever sighted. (We now know the “great bay” was actually Tampa Bay—which was not north, but south of their original landing.) Narváez simply moved on to other villages where stolen food, especially corn, quickly became the catch of the day. When one of their own horses was wounded in battle, the animal would be finished off and fricasseed for the next day’s meal.

THE FIRST ESCAPE

If we can assume anything about Esteban at this point, we would think of him on the lookout, walking alongside Dorantes and his horse—the both of them in ever-present survival mode—of a mind to assist his master in any way. His ticket to fame was yet to be punched.

Andrés Dorantes

Eventually the leaders all agreed they must return to the sea, fighting those whizzing arrows all the way. When they arrived at a satisfactory inlet, scouts confirmed the Gulf was close at hand. They devised a plan to make their own boats from trees, and one of the men contrived a forge, allowing them to smelt any available armor and iron into tools and shapes that would be needed. The effort took weeks. While building the boats, they continued to fight Indians, and steal food. They made five boats with room enough for about 50 men in each.

Once on the open sea they would head for Mexico, hugging the shore as best they could in their handmade boats. Curious Indians would approach Cabeza de Vaca’s boat, gawking at the surviving occupants from their canoes, offering food sometimes, but never shelter. The storms were horrific. The survival epic took months, and as they passed the Mississippi they gave thanks to God, for they were able to paddle close in and drink some fresh water.

THE ISLE OF MISFORTUNE

Early in the first episode of the Ken Burns production “The West” (1996), the camera scans a colony of gulls flying over a roiling sea under stormy skies. Veteran narrator Peter Coyote takes the reins.

On a cold morning in the autumn of 1528, a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico blew a frail boat onto the coast of Galveston Island in what is now Texas. A handful of Spanish soldiers staggered ashore. They were the first Europeans to set foot in the west.

The reference here is to one of the five boats, specifically that of Cabeza de Vaca and his crew, precisely as written in the “Account.” The Spanish were dehydrated, near-death, and starving. For a time, the local Indians—the Karankawa—welcomed them, providing nourishment and shelter, but within a few weeks these same native inhabitants also began to suffer—from cholera. Many Indians died and they argued over whether to blame the outbreak on the Spanish. Speaking of the invaders, the narrator continues:

They had hoped to come as conquerors.

Instead, they entered the West as captives.

All true, but … merely captives? In his own “Account,” the word that Cabeza de Vaca himself used was slaves. So whether or not the Indians thought of it that way, and whether or not historians agree, from the Spanish point of view the tables had turned.

Cabeza de Vaca’s “Account,” cover illustration

Of the five boats that left Florida, only two were able to land safely on the island. All men on the other three boats, including Narváez, were lost at sea. In the two boats that landed successfully, only fourteen men made it to the beach. Over time more deaths piled up as crew members scattered—a few leaving in search of other tribes, a few killed by Indians for showing hostility, others dying from starvation. Cabeza de Vaca escaped from the island to the mainland, but afterward another tribe took him captive. He soon submitted to the misery of doing the slave work.

After two years of this long ordeal—it may have been something like three or four—Cabeza de Vaca escaped and returned to the island where he heard from other Indians that two white men and a black man were staying with another tribe. On meeting up with them, he found his companions alive: Dorantes and Esteban and Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, another of the captains.

MEDICINE MEN

At long last, we meet Esteban—who is not mentioned in Cabeza de Vaca’s “Account” until almost everyone else has disappeared or died. The four men were soon forcibly separated from each other but still managed to communicate and occasionally visit amongst themselves. There was hope that their very proximity foretold a possible escape.

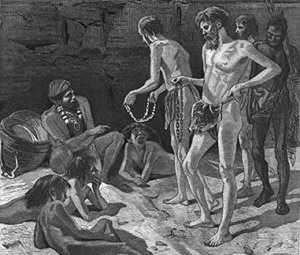

We are told several times in the “Account” that each man cut his own dashing figure in the flesh—for unlike the featured painting on the cover of Cabeza de Vaca’s “Account,” not one of them had any clothes whatsoever, neither survivors nor Indians.

I have said already that we went naked in that land, and not being accustomed to it, we shed our skin twice a year, like snakes. Exposure to the sun and air covered our chests and backs with great sores that made it very painful to carry big and heavy loads, the ropes of which cut into the flesh on our arms.

— Cabeza de Vaca, “Account,” Chapter 22

The tribes here were hunters and gatherers—spending long hours each day tracking animals and looking for roots, prickly pears, grasses and tubers … just to stay alive. As a result, the Indians as well as the expedition survivors were always foraging and forever hungry. During his job scraping skins Cabeza would “keep the parings” which could be eaten in secret. The Spanish sometimes secretly ate raw meat “because if we broiled it the first Indian who came along would snatch it away and eat it.”

At last, here was an opening. For when the Indians were sick, infected or diseased, as they often were, their medicine men would “make a few cuts where the pain is located and then suck the skin around the incisions … cauterize with fire … and breathe on the spot where the pain is.” When that did not do the trick, Cabeza and Castillo might be approached. These men came up with their own spiritual cure, to wit: “make the sign of the cross over them while breathing on them, recite a Pater Noster and Ave Maria, and pray to God, our Lord.” (Cabeza de Vaca, “Account,” Chapter 15)

It worked—and that’s all I’m going to say. And whatever you want to call these Europeans—shamans, faith healers or witch doctors—the Indians themselves were taken in. They would shower the men with gifts of gratitude, bows, arrows, flint stones, skins, baskets of fruit, venison, and even, for the cold nights, hides. The healthy as well as the sick asked to be blessed. As time went on, their reputation received a boost among other tribes, and it dawned on the Europeans that perhaps they could sell their services on a “world tour” of other tribes and nations.

Simply put: their nonstop survival instinct was now evolving into a groupthink of cunning and intrigue. Their first successful escape was from the seasonally-itinerant Karankawa to the perpetually-itinerant Avavares—not a total relief, but at least they had removed themselves from a slave-like existence because the Avavares had heard about the healing.

During that time people came to us from far and wide and said that we were truly the children of the sun. Until then, Dorantes and the Negro had not cured anyone, but we found ourselves so pressed by the Indians coming from all sides that all of us had to become medicine men. We never treated anyone that did not afterward say he was well.

— Cabeza de Vaca, “Account,” Chapter 22

There are few conquest chronicles as entertaining or as colorful as Cabeza de Vaca’s account. But towards the middle of the journey, he does tend to get lost in the details. Timelines become hazy. Details grow exaggerated. The facts behind Esteban are often contradictory.

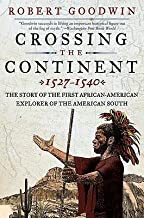

ROBERT GOODWIN

“CROSSING THE CONTINENT: 1527-1540” (2008)

Robert Goodwin

Robert Goodwin is a British historian whose specialty is the Spanish conquest of the New World. This book, one of two he has written for popular history buffs and professionals alike, is definitely not for the factually faint-hearted. But by virtue of his fair treatment of the many historical sources, he happens also to provide our featured novelist Leila Lalami with many of her realistic settings.

As for their planned break-out, Goodwin says, the survivors lucked out. It was the late summer of 1534 and well into the “prickly pear season”—the ripening of the red-purple fruit of the prickly pear cactus, a crucial source of food for the Indians—and would-be escapees. The Karankawa hunters of every settlement were away on a hunt. Each of the survivors had agreed some months earlier to sneak off by the light of the next full moon and meet up at an “inland heath” known for its prickly pears. There, they had agreed for Esteban to lead the way.

That same day they escaped and rushed headlong … through a hitherto hostile land …. Although the four men found few ripe fruits on the prickly pears, there were enough to keep them going. … Esteban had become their leader … he went first and blazed their trail. [and by going first] Esteban now controlled the Indians’ understanding and image of the survivors.

. . .

He was the first to meet the Indians, to talk with them, to tell them who he was and who the white men were. From this moment onward, Esteban became the agent of the survivors’ constant movement, negotiating with the Indians, choosing the roads they would take, the byways they would explore, and the nations and tribes they would meet.

— Goodwin, “Crossing the Continent” Chapter 16

Although they wintered that year with the Avavares, regular postings of their success ensured that their reputation preceded them even into the hinterlands. Rumor was indeed their salvation.

*

Their internet of the day? word-of-mouth. Their hashtag? #healers. Their growing reputation allowed them to move quickly from one itinerant tribe to another, and eventually from the smaller settlements to larger villages all across northern Mexico and the American southwest.

Their internet of the day? word-of-mouth. Their hashtag? #healers. Their growing reputation allowed them to move quickly from one itinerant tribe to another, and eventually from the smaller settlements to larger villages all across northern Mexico and the American southwest.

They followed the Rio Grande river and along the way encountered Indian cultures based on agriculture. In nearly all of the settlements they found, an aura of the supernatural was bestowed upon them. Tribes would send messengers to other villages, passing the word that the “Children of the Sun” were coming to heal the sick and, by their blessing, bring prosperity. They happily joined in stalking deer, they smoked tobacco, and they also celebrated with the Indians.

On this point, there is no hint of cynicism in the accounts of Cabeza de Vaca. The Spaniards accepted their own cooked-up belief that their shamanistic sham, as it were, was an inspiration and gift from God. With it, they carved out a niche for their Catholic teachings as well. But it was their will to live that supplied the power for the survivors to move on and tell their story of salvation.

As for Esteban? Any slave would have no choice but to play along.

One Spanish conquistador, a man who knew Esteban, reported that he always wore his shamanistic finery: a splendid feather headdress and jangling bells strapped to his arms. He carried his shaman’s scepter, a richly decorated gourd, the native rattle from near Monterrey in Mexico which was a symbol of his power and which sounded like the sinister drone and cackle of an angry rattlesnake. He had a collection of fine ceramic plates decorated in many colors, no doubt personal souvenirs. Another history described how Esteban developed friendships with the people [Indians] of northwestern Mexico, so much so that they pressed upon him gifts of turquoises and other valuables. They even offered him their womenfolk ….

— Goodwin, “Crossing the Continent” Chapter 17

It did not happen overnight, but on this long trek home clearly a gutsy and flamboyant new Esteban emerged. He began experimenting with this cover, and soon the team was making its way through grateful tribes on the way back to civilization. In case you hadn’t noticed, there is a variety of Estebans that have been imagined by our contemporary artists, portraitists and sculptors—and, who knows, perhaps, one day a movie director as well.

THE SCOUT

As they moved on, there were fewer and fewer teepees, more and more settlements, agricultural fields and “oasis towns” where they first sampled corn tortillas and beans, fish and “hearts of deer.” The tribes were generally more friendly and welcoming. Many Indians indicated there were more riches to be had in the north, but the team, anxious to return to civilization, chose to head west, in the direction of modern-day Sinaloa, taking the roads that would be likely to lead to Mexico City.

Esteban’s ability to interact with unknown tribes and communities was uncanny. To do this successfully, historians believe it was in part due to his being born into a coastal trading culture that was chock full of many languages: Arabic, Portuguese, Spanish, some central African. It also seems apparent that Esteban had been personally endowed with rare linguistic affinities.

We had the Negro talk to them all the time; he inquired about the road we should follow, the villages—in short, about everything we wished to know. We came across a great variety and number of languages, and … they always could understand us and we them.

— Cabeza de Vaca, “Account,” Chapter 31

As they made their way into northwestern Mexico, Indians from each settlement would join the throng. The numbers gradually swelled to hundreds, maybe more.

In this more realistic representation, Esteban is shown standing behind Cabeza.

But they soon began to hear from Indians who were afraid of the “Christians on horseback”—men from the south who would make slaves of them. In fact, the further south our survivors trekked, the fewer Indians they found upon the plains, as many had fled for their safety to the mountains. Along the way the survivors also encountered Spanish who had been looking for Indians to enslave, unsuccessfully however, and as a result, had lost their way and were malnourished. Such lone desperados had no way of acquiring food other than thievery.

It seemed Cabeza de Vaca and Esteban had no end to their distractions but soldiered on as best they could at every opportunity.

When we reached Compostela, the governor received us very well. He gave us what he had for us to wear, but for many days I could bear no clothing, nor could we sleep anywhere but on the bare floor. Ten or twelve days later we left for Mexico.

— Cabeza de Vaca, “Account,” Chapter 36

A NEW EXPEDITION

Safely in Mexico City, the survivors were nursed back to health, celebrated, wined and dined, and eventually able to wear clothes again. The three captains gave verbal testimony to the high court of conquest, the “Audiencia of Mexico.” Esteban himself was not called to testify since his actions were not legally his own, but rather carried out in service to his master Dorantes.

Following the official hearings, both Dorantes and Cabeza de Vaca left for Spain. Castillo married and receded from view. But within a few years, the Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, a reformer, was eager to pursue a mission into the unexplored territories of what is today the southwest United States. The prize to be had? The Seven Cities of Gold.

Both Church and State were angling for this jewel, both intending to claim some real estate for the Empire and at the same time convert and minister to the Indians. Their competing interests resulted in a pact. Viceroy Mendoza offered to set aside all brutality and slaving that had been the norm for years. Archbishop Juan de Zumárraga envisioned a “peaceful conquest.” And for these goals, they insisted on an expert translator, and Esteban fit the bill. He brought along his brash multicolored costumes, his personal savvy and the charm to go with it.

The leader of the mission was Marcos de Niza, a Franciscan friar with the usual dubious credentials. His second-in-command, if you will, was “another Franciscan, Brother Honorato, a young friar eager to proselytize the heathen of Arizona and New Mexico” (Goodwin, “Crossing the Continent” Chapter 19).

De Niza was the titular head. Esteban would shoulder all the technical responsibility and establish first contact for all native populations they discovered. He was to be assisted by Indian guides who would be picked up along the way. And finally there would also be a commander-in-waiting, the ambitious Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, who would afterwards undertake the full expedition. At the moment, however, Coronado was busy neutralizing internecine strife, which is to say Indian uprisings in need of a little suppression.

In March 1539, the Franciscan mission proceeded on schedule. Their command was comprised of (1) two inexperienced Friars, (2) one Moroccan scout dressed as a medicine man, and (3) a cadre of Indian guides who likely had never travelled very far north.

What could possibly go wrong?

THE LAST HURRAH

Marcos de Niza’s “Account” to the authorities (1538) is the primary source material for Esteban’s second mission in search of the Seven Cities of Gold. The problem is that the document he wrote is now seen by many historians as fanciful and wildly inaccurate on details, timings and locations. Nevertheless, the general drift of their progress is fairly straightforward.

Initially the mission took a northwesterly route along the Gulf of California. Esteban already knew much of the terrain—where the fertile valleys were, where the rivers flowed, where mountains and deserts might impede progress. On this first leg, Marcos de Niza and Esteban crossed over into Indian lands. They arrived at a settlement called Vacapa, located in modern-day Sonora. They were warmly greeted, and the Indians were especially wowed by Esteban’s showy outfit.

Marcos de Niza with an Indian guide

It was April, and before heading to the next Indian settlement, de Niza was busy planning services and blessings for Holy Week. But they needed to proceed on schedule, so de Niza settled on a plan for all of the subsequent destinations. At each village, Esteban would depart a few days ahead of de Niza’s team. He would take his own platoon of Indians to establish relations, and he would send back signs or verbal messages. If Esteban should ever see the Seven Cities, de Niza instructed, he should send back a messenger with a cross, carved to represent the size of their magnificence: small, medium, large.

As it developed, however, Esteban did not stop here and there. He did not wait at each village as he was told to do. Instead, he just kept moving.

After leaving Vacapa, Esteban decided to disobey Marcos’s order to wait for him fifty or sixty leagues farther along the trail. Instead, Esteban put as much distance as he could between himself and the friar, and it seems likely that he had decided to escape. He had become a cimarrón, a runaway slave.

— Goodwin, “Crossing the Continent” Chapter 20

Escape? Well, that’s one historian’s viewpoint. But it has always been curious that Esteban put a goodly number of miles between himself and the Friar—so many miles, in fact, that it would take a week or more before Marcos de Niza could hope to catch up with him.

At long last, Esteban’s Indian messengers sent back to Marcos an announcement that he had found the first city of gold, which was in actuality the multitiered pueblo that the Zuni Indians themselves called “Hawikuh.” From the comments ascribed to Marcos de Niza, it would appear that Esteban himself may have been responsible for the Spanish christening: Cibola.

The Zunis today call themselves A:Shiwi, Esteban called their lands Shivo:a, which sixteenth-century Spaniards wrote as Çivola or Cibola.

— Goodwin, “Crossing the Continent” Chapter 20

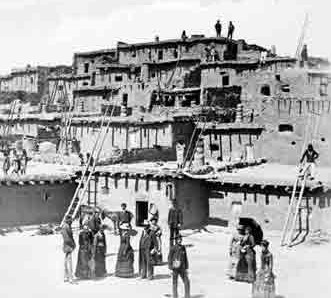

The Zuni Indians were farmers and traders, and many other tribes knew about them, and had traveled there. Their unique “city” was indeed an impressive sight, an ancient pueblo of multi-level houses built of rock and clay and wooden ladders, unlike any other in the experience of the discoverers. But to the Spanish, it was something of a disappointment. It wasn’t modern or sophisticated. It wasn’t bejeweled. It had neither the size they had heard about, nor the sparkle they were hoping for. In essence, it wasn’t Tenochtitlán.

Zuni Pueblo in the 1870s – Visitors in foreground

Before approaching the pueblo, Esteban “is said” to have left his own Indian escorts behind. Did Esteban make contact with the Indians at Hawikuh? It is likely, as there appears to be corroborating evidence for that. Did he return? No, he did not, and in fact was never heard from again. Did his Indian guides, upon returning to Marcos de Niza, have a story to tell? Oh yes, very much so, and that story grew into legend. Esteban, they said, was killed by the Zunis. Friar Marcos de Niza turned their story into literature that you can still read about in books and on the web.

But all the “knowledge” of Esteban’s death relies on the believability of Marcos de Niza. The Indians were never interviewed, and several researchers now have their doubts. Up for grabs are at least three outcomes:

- Esteban was killed by the Zunis for one of several traditionally-cited reasons, foremost among them:

(a) the claim that Esteban overstepped his bounds by coming on to the women.

(b) the Zuni council suspected he was a spy, and then beheaded and quartered him. - Esteban died in battle after his Indian support came to help.

- Esteban disappeared by sneaking away.

For the first two scenarios, no expedition member was present at the killing. Other than the unreliable Marcos de Niza, there really are no other primary sources of evidence, beyond hearsay. There are nevertheless many stories and shadowy legends that continue to circulate—none of which have been officially sanctioned by the famously tight-lipped Zuni officials. In the words of Larry McMurtry, whatever truth there is has “long since been heavily marked over by the crude pencil of legend.”

A few historians including Robert Goodwin believe that Esteban may have indeed escaped the Spanish and his enslavement, with or without the help of the Zunis—that he may have lived out his life elsewhere, in other words, possibly among Indians as a free man. If so, he certainly could have trekked eastward, back in the direction of the Rio Grande. Most certainly he would have had many contacts in his address book.

*

Coronado leading his expedition on white stallion.

Illustration by Frederick Remington

Coronado arrived a year later, with 300 soldiers and his own supporting cast of, yes, 1000 Indians. In this, his only major battle and his first bloody conquest, the Spanish brigade made toast of Hawikuh. Of interest to us, however, is Coronado’s “Letter to the Viceroy” submitted on August 3, 1540. There, in one small paragraph, he addresses Esteban’s fate.

The death of the Moor is a certainty because many of the things he was carrying have been found here. The [Zuni] Indians told me they killed him here because the Indians from Chichiticale told them he was a wicked man and not like the Christians. Because the Christians did not kill anyone’s women, but he did kill them. And also because he was touching their women, whom the Indians love more than themselves. Therefore they decided to kill him, but they did not do it in the way that was reported.

— Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, editors,

“Documents of the Coronado Expedition” (2012) p. 262

Did Coronado really believe that Esteban went around touching and killing Indian women? As if to contradict himself, just two paragraphs later he complains about the lying, dissembling and equivocating he found to be common among the Indians, especially concerning the source of Zuni gold. Then he basically just throws up his hands.

And I see that they refuse to tell me the truth about everything.

— Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, editors,

“Documents of the Coronado Expedition” (2012) p. 262

Coronado left Hawikuh a few weeks later and followed his Indian guides all the way to the Great Plains of the northern continent, in what is now Kansas. He never found the Seven Cities of Gold.

LEILA LALAMI “THE MOOR’S ACCOUNT” (2014)

Esteban’s skin color and features both puzzled and delighted the Indians of the southwest and seemed to be considered an asset by the Spanish. Some historians and anthropologists argue he was originally from central Africa, while others go with the Moorish or Mediterranean heritage that Cabeza de Vaca assumed.

We know enough to know we don’t know. We know the Portuguese slavers operated out of many ports, including Azemmour. We also know they often sold their slaves to the Spanish. And we know the slaves came from both north Africa and the central African cultures. Robert Goodwin, whose book we surveyed above, devotes ten pages to the subject of the Moor’s probable ethnicity. Yet after more than a century of speculation and digging through archives, there is still no agreement—all the options are still on the table—and unless a birth certificate or engraving of Esteban turns up, our subject’s mysterious beginnings will likely remain unsolved.

We know enough to know we don’t know. We know the Portuguese slavers operated out of many ports, including Azemmour. We also know they often sold their slaves to the Spanish. And we know the slaves came from both north Africa and the central African cultures. Robert Goodwin, whose book we surveyed above, devotes ten pages to the subject of the Moor’s probable ethnicity. Yet after more than a century of speculation and digging through archives, there is still no agreement—all the options are still on the table—and unless a birth certificate or engraving of Esteban turns up, our subject’s mysterious beginnings will likely remain unsolved.

Except, of course, in a novel.

It was the year 934 of the Hegira, the thirtieth year of my life, the fifth year of my bondage–and I was at the edge of the known world. I was marching behind Senor Dorantes in a lush territory he, and the Castilians like him, call La Florida … a large island, larger than Castile itself, and it ran from the shore on which we had landed all the way to the Peaceful Sea. …

… I had not wanted to come here … the journey across the Ocean of Fog and Darkness had been marred by all the difficulties to be expected of such a passage: hardtack was stale, the water murky, the latrines filthy … the worst of it was the smell—the indelible scent of unwashed men, combined with the smoke from the braziers and the whiff of horse dung and chicken droppings … a pestilential mix that assaulted you the moment you stepped into the lower deck.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 1

*

Would it have occurred to any Spaniard of the 1530s that their Moor might have a history of his own, let alone write a first-person “Account” of the expedition? This book, by Moroccan-born novelist Laila Lalami, purports to be his secret weapon against the daily cruelties of slavery and the cooked-up superiority of the Spaniards. It both confirms the abuses and shatters the idea that “The Conquest” was in any way righteous, or morally correct.

In this novel he not only has a name, he has a fantastic story to tell. He is Mustafa ibn Muhammed ibn Abdussalam al-Zamori, who for now we shall simply call Mustafa. (In case you are wondering, the “ibn” in his name should be read as “son of” and the “al-” in the surname as “originally from”).

When the book opens, we are viewing the landing in Florida through the lens of this Arab, who is about 30 years old, enslaved for five years or so, and still unaccustomed to serving the whims of a master. In chapters that alternate between the Florida expedition and Mustafa’s youth, Lalami treats us to his origin story and early life in Azemmour, all told in the first-person. Eventually the chapters no longer alternate but come together in a timeline that corresponds to when Cabeza de Vaca first learns of the survival of Dorantes and Esteban on the Isle of Misfortune.

But really, you ask, how could a slave even begin to write his own story? We learn in the second chapter of this novel that it was the doing of his father, a stern but humble notary who had fled the city of Fez around the year 1500, during a mass immigration of Jews and Arabs who were fleeing forced conversions to Catholicism in Spain. So it was, from the age of seven, Mustafa attended school at the mosque in Azemmour, which included several years of reading and writing lessons from the fqih, a scholar who taught the Quran to children.

From a very young age, Mustafa’s mind was elsewhere. Especially as he grew older, he felt drawn to the souq, the marketplace. Mustafa never wanted to become “a recorder.” He wanted to be with boys his own age. And in his heart, he yearned to become a merchant.

On Tuesday, which was market day … the other boys were able to run around, exploring stalls, eating sweetmeats, watching a dancer or a snake charmer, or otherwise getting into mischief, while I had to sit in a dark, musty classroom with my fqih. Before long I began to skip school in order to … visit the souq. There I watched fortune-tellers, faith healers, herbalists, apothecaries, and beggars. They promised a healthy child, a painless life, a pliant husband, a dutiful wife, or a path to heaven, perhaps different versions of the same things.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 2

Very much not what his father desired for his eldest son, for whom the prescription would be a respectable job and a religious life, all aspects of which his loving mother reinforced with home cooking and parables of children gone astray.

The City-State of Azemmour, hand-colored, as depicted in a manuscript, circa 1572

Gradually Mustafa realizes he must help his family as his father grows older. He has two younger brothers, and with his father’s health declining, he grinds away at school and finally graduates with a certificate. Soon, however, he takes leave of his education. He seeks an apprenticeship, and eventually sets up his own business. As his own middleman, he is on his way to becoming a merchant. His heart-broken father can never cope with the news.

Also in those days there was a legitimate slave trade coexisting alongside the restrictive Muslim judicial system. One day:

I was negotiating the price of seven loads of wheat destined for Lisbon. The farmer selling the grain … brought with him three slaves he had unexpectedly inherited from an old uncle. Do you know of a buyer? …

Sixty for all three, I said.

From that sale, I derived a profit of one hundred and fifty reals …. I was stunned at how easy it had been and how high the proceeds.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 4

This simple bid for a cut of the action—how quickly it transpired! Had he not felt even a tinge of sympathy for the slaves? Had he not a moment of remorse after looking at their faces? Here is Lalami, drawing for us a brash, young, ambitious Mustafa—now a man of the street, a young Arab on the cusp of success, savvy yet literate, now able to exploit the system. In this one brief transaction, Mustafa feels the awful irony of his choice: “I consigned these men to a life of slavery and went to a tavern to celebrate.”

*

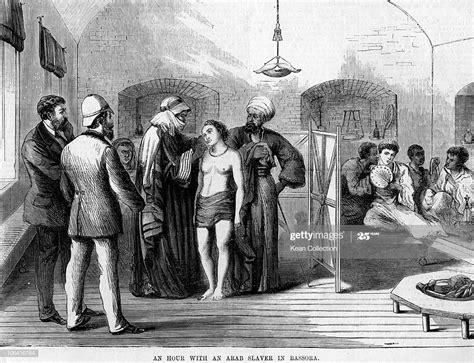

History tells us there were two back-to-back disasters in Morocco during the early decades of the new century. In 1513, the citizens of Azemmour were refusing to pay taxes to the Portuguese, and in response the Portuguese had shut down the harbor with a naval blockade, an act of war which brought the once-proud city to its knees. In a swift invasion, Portugal took possession of the town, controlling trade and shipments.

Then, around the year 1520, a devastating drought beset the area, striking both southern Spain and northern Africa. Over the space of two years this scourge further wrecked the local economy of Azemmour, and day by day working families lost jobs, and there was less and less food. The sheiks were blaming the calamity on greed, loose women, even the inns that sold wine. “Every story needs a villain,” Mustafa’s mother says grimly.

Within this historical inferno of politics and drought, Lalami creates the perfect fit for her story of the Esteban timeline. It is only a matter of a few years before Mustafa’s aging father loses his livelihood, and in time, dies. Mustafa himself falls victim to the economic collapse, losing his startup business. With the family barely scraping by, he too must grapple with the crushing reality of their poverty. His mother is reduced to making soup from salt, cumin and chicken bones. In the depths of his despair, he struggles with the idea of proffering himself to the slave merchants at the dock.

A young man being offered by an Arab Slaver

In those days many children, especially daughters, did in fact “flee into slavery” (what is sometimes called voluntary slavery) to help their families pay off ruinous debt. Finally, at his lowest ebb, Mustafa approaches the slavers at the docks. They immediately recognize him. He brings his brothers with him, but they are standing some distance away. The jaded traders have seen everything. The brothers watch as Mustafa steps forward, as the men prod his muscles with a stick, as they find his eyes sufficiently good and confirm his teeth are all in place. Then one asks: “Are you sure you want to do this?” He assents.

The younger siblings still have no clue what he is up to until Mustafa turns to them and dispiritedly hands over the money—payment from the sale of his own life into servitude. He hugs them and sends them grieving back to their mother.

Of all the contracts I had signed, this was the only one my father could not have imagined me signing, for it traded what should never be traded. It delivered me into the unknown and erased my father’s name. I could not know that this was just the first of many erasures.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 6

*

For all intents, Mustafa now becomes Esteban. He is thrown into the life of a household slave. At his christening in Seville he writes: “Here in this high-ceilinged church, I felt small and helpless.” (“The Moor’s Account” Chapter 8).

The slave Esteban is forced to navigate a maze of indecipherable Spanish customs. He is mercilessly flogged by his master, beaten for kneeling on the floor, kicked for chanting mantras. The battering continues until he learns to pray in silence. There is another Muslim slave in the household, Elena, a female who has been similarly severed from her family. Gradually a bond of sympathy forms between them, which they both know cannot last.

Several years pass, each day an eternity. But one day he is called to court, where his first master confesses there is a debt he cannot repay. A nobleman by the name of Andrés Dorantes steps forward and explains that he is taking the slave as payment. It is all news to Esteban, for what at first seems a release could easily become just another enslavement with a new unpredictable master.

Esteban never returns to the house of his former master. He never has a chance to say goodbye to Elena. Instead, he finds himself standing next to his new owner on the deck of the Gracia de Dios.

Epilog

When we first hear of Esteban’s story and his many successes on the missions, we almost feel like rooting for him, as if he were an underdog. But at the same time, it seems not entirely consistent that a slave who witnessed many cruelties could so easily be fooled by the Spaniards’ goals. The very idea that an African slave can so willingly sign on to the conquest narrative rings false. Lalami’s novel serves as a corrective.

Leila Lalami

To appreciate this, let’s backtrack to the first battle after the Florida landing, an immensely bloody affair with bullets and arrows flying faster than lances. After the skirmish, the Spaniards solemnly bury their own dead, as reported by Cabeza de Vaca. In the novel Esteban steps away to prepare the evening meal for Dorantes. In language that Cabeza de Vaca would certainly consider too vulgar to include, Esteban passes a pile of Indian bodies, stacked up against a cypress tree, and we readers are instantly thrown into the dark side of the Conquest.

The heap of bodies, with arms and legs jutting out at odd angles, smelled of decaying flesh. The odor wrapped itself around my throat like a noose …. Some of the bodies had been mutilated, their nose, ears, or fingers cut … and hung from strings as keepsakes.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 3

Even as the expedition progresses to Apalache at the beginning of this novel, we begin to witness the differences between what Lalami’s Esteban perceives and what we know is in the official account. In many ways large and small, we gradually come to doubt Cabeza de Vaca’s veracity. Narváez’s men take Indian women in the wake of their village assaults. Dorantes is revealed as often fickle, changing his loyalties among the conquistadors as suits his mood. Torturing is seen as commonplace. It is in these forests and everglades that Esteban comes into his own, rising from a humble memoirist to committed participant and underground chronicler.

In Lalami’s portrait of Esteban we have not so much a slave as a fellow traveler who paints Cabeza’s original episodes in far more vivid detail. He contributes to the work of making boats, mending sails and seeking out food, but in his heart, he is privately sorrowful, suffering from a creeping forgetfulness, dreaming one night of returning to his mother and his brothers—none of whom recognize him. Chapter by chapter, Muslim and Christian are thrown into contrast. The hypnotic rhythm of his thoughts, his observations, and his remorse feed into his sympathies for the natives.

As he is wont to do throughout the novel, Esteban tasks himself with little kindnesses here and there, as when secretly feeding the tortured Indian prisoners.

How strange I must have seemed to them: not a conqueror, but the slave of a conqueror, who had brought them the small comfort of a little food. Perhaps this led them to think of me as a good man … but I had once traded in slaves … it shamed me that I caused the suffering of others.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 3

*

In her book, Lalami has brought us to a crossroads—the intersection of Esteban the historical enigma and a fictionally-fleshed-out human being. Tormented by his past and uncertain present, the fictional Esteban/Mustafa is poised to make something better of his life. It soon becomes clear that he will rely on his native talents, and we see him as passionate and empathetic—“fictionally real” if you will—capable of achieving a level of humanity that historians always knew was there, but perhaps could never convey through the evidence.

Esteban at the lead. Marcos de Niza and a conquistador follow closely behind on horseback (lower left).

For some of you, this fictional Esteban is a temporary detour. For me, a door was opened. At the very least it seems likely that the real Esteban could never fully identify with the Spaniards, and in fact he was never released from bondage. As a slave he had nothing to lose. He threw his heart and soul into the journey—come what may.

The three other survivors are conquistadors through and through. They have no yearning to stay among the Indians (though a few other survivors actually did remain in Texas voluntarily, Cabeza tells us). The Spaniards must at all costs get back to civilization to reclaim their land, their lives, their family and their rewards.

We can imagine other dramatists, novelists or film directors playing out their own narratives for this same shadowy figure. But surely each of them would emphasize an Esteban who seems committed to communicating with the people in the “Land of the Indians,” and frequently conveys his own reverence for the tribulations of a life of hardship in this vast, inhospitable countryside.

Cabeza de Vaca’s quaint tales of his healing of the sick provide a special insight into the added value of a fictional enhancement. Cabeza would have us believe that he alone cooked up his “cure” which was not, in his telling, medicinal at all but really a claim of divine intervention, a “laying on of hands,” what today we would call faith healing.

For the realist Leila Lalami, on the other hand, the healing could never have been heaven-sent. If it was as effective as the Indians declared, the techniques must have been sourced from the empathy and depth of the survivors’ own experiences.

From [Chaubekwan of the Yguaces tribe] I learned how to grind roots without destroying their power, how to store medicinal plants, how to prepare various poultices, but also how to wear a costume and entice a patient to drink a bitter potion.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 15

Among another tribe, the Avavares, the local medicine man observed Esteban mixing an “infusion” to settle Dorantes’ stomach.

He wanted to know how I had prepared it, how much of it I had used, and whether it was safe to give to a child as well as a man. I told him what I knew: it was a simple remedy my mother used whenever I complained of stomach ache.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 16

Esteban could also be stumped now and then, as were the others, but his particular ruse was to employ a magic “cupping cure,” a trick he had learned in the Moroccan souq, placing heated cups on different parts of the shoulder or body, then lifting it and releasing the pain into the air, “in order that I might mitigate any failures.” In the novel, it bought him some time to investigate further.

Dorantes and Cabeza de Vaca used soldiers’ remedies they had learned when they fought in their king’s wars. As for me, I used what I had learned growing up in Azemmour. I gave infusions of wild garlic for pain in the joints; I cleaned wounds with the ground back of young oak trees; I treated constipation with verbena; for a sore throat, I suggested gargling with salted water. If I was confronted with an illness I did not recognize, I listened to the sick man or woman and offered consolation in the guise of a story … something I had learned in the markets of Azemmour: a good story can heal.

— “The Moor’s Account” Chapter 16

There are many such refreshing turns in this historical novel. Esteban’s desire and hope to be free flows quite naturally from the first pages. He communicates with the Indians always in their language and by looking the part of a shaman from the East. The hypnotic rhythm of his thoughts, his observations, his remorse—these all-to-human characteristics feed his hope to be free again one day.

Additional Sources

- Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, editors, “Documents of the Coronado Expedition” (2012)

- Dennis Herrick, “Esteban” (2018) — a comprehensive examination of the facts; debunks off-repeated legends, and unsubstantiated claims

- Larry McMurtry, “Sacagawea’s Nickname: Essays on the American West” (2001) – Chapter 5: Zuni

- Geoffrey C. Ward, “The West: An Illustrated History” (1996) – based on the Ken Burns film script

Media

- Chicago Humanities Festival – Nov 24, 2014, Lalami video interview by Gina Frangello, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rRbEMK5zE1w

- National Book Festival, Lalami video interview by Bilal Qureshi, Nov. 28, 2016 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIZ9e_Lsg30

- University of South Florida, “Le Moyne Engravings” — http://fcit.usf.edu/florida/photos/native/lemoyne/lemoyne.htm

One Response to “Esteban in His Own Words”

Truly astounding that one man could have lived so many lives. His willpower seems only matched by his intelligence.

I had not heard of Esteban before but I am enthralled now.

Thanks for a really engaging read.