M Train

There is a situation that plays out with friends only. It goes something like this: first, the friend gives or loans you a book that they loved, and you are grateful, hoping this will be your next shared experience. Then there’s a space of time (sometimes a LONG space of time) during which you are reading, or trying to read, or not getting around to reading—and your friend is patiently awaiting the news. Eventually, though, it comes out that maybe you did not quite like the book–oh yes, that book they loved so much and just knew you would too. You come up with an excuse like “I couldn’t quite get into it”—but however much a friendship warms to the touch, we find now and then that the gulf between our souls is a wee bit wider than we want it to be.

Patti Smith

“M Train” (2015) by Patti Smith is the loaner (Diane)–above referenced, gratefully received, difficult to fathom. It is Ms. Smith’s second memoir by the way; a kind of memoir wrapped up as travelogue-exploration-

I really knew squat about Patti Smith. Her name, yes—and her top-40 hit “Because the Night”—you still hear it now and then—but delving into “M Train” I knew immediately I was missing something because you don’t get too far into the book when it dawns on you that the author is expecting you to know a bunch of other things about her. For a while I ventured on—but I kept thinking, jeez, there seems to be a world of shared experience here I hadn’t known anything about.

So for sanity’s sake, and to save myself a lot of unnecessary background reading, I called another friend, Ruth Banes—for many years a professor of American Studies at the University of South Florida—and for me, the closest thing I know to pop-culture-geek.

Ruth set me straight. “You’re right,” she said. “If you don’t know much about Patti Smith, you’ll probably need to read her earlier memoir just to get in the groove.” Ruth explains the earlier memoir—”Just Kids” (2010)—is where Smith tells the story of her life in New York with artist and photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. A dim light goes on in the basement of my aging mind. Oh yeah . . . that guy. I had heard something about Mapplethorpe and seen some of his shockingly-out-there art—but I didn’t know he and Smith were friends or whatever, and certainly knew nothing of their youth. They really were, to me, little more than two names from the era.

PATTI SMITH “Just kids” (2010)

So I drop the meandering “M Train” and opt for “Just Kids”—which is lovingly told, I will say that. At age 21 Patti Smith arrives in New York penniless and having to live on the street for a while, and she and Mapplethorpe meet and “fall in” together, somewhat romantically at first, but over time developing a loving bond and devotion to each other’s art. It’s the late-60s. Smith, the more practical of the two, saves her money and works in bookstores, while Mapplethorpe suffers through, and loses, many odd jobs. I would say most of the book is taken up by their efforts in getting to know other artists and poets and singers, including their friends and acquaintances at the famed Chelsea Hotel (“my university” she says).

It’s an affecting story, and the interest is held by their inch-by-inch progress toward their divergent goals—she, BTW, has an incredible knack for day-to-day details—a keen memory—or possibly a fact-packed diary. But Smith’s predilection for simple-sentence raw-fact-recital becomes a bit of a chore for me—told in a way that plows the fields of day-to-day life if you are up for that. No doubt a lot of her fans are appreciative, as, in both memoirs, a life lived for art is the dominant theme.

The two lives in “Just Kids” are really more kindred spirits. They share a hunger for creating something NEW. They meet up with many, many others over the years: skirting the edges of the Andy Warhol group, drinking and smoking and “dropping” with almost everyone on the scene—and eventually things do happen. Mapplethorpe’s drawings and sculptures take a life-changing turn when he is gifted with a Polaroid camera. Smith’s knack for offbeat poetry is transformed to performance art when she is cajoled into reciting at St. Mark’s Church alongside Lenny Kaye’s improvised guitar accompaniment. What happened was the naturally shy Smith realized something about herself—that she became a tiger in performance. She is the beneficiary of Mapplethorpe’s drive for notoriety, as well: you get the feeling that if it weren’t for Robert, the shy Patti might never have gotten to know the many others that scooted her along.

On the other hand, she might have succeeded anyway. Patti Smith is, if nothing else, Artistic Temperament Writ Large. That she is also decent, family-loving, practical, genuine, and endearing—well, it does seem to rattle the way we want to look at Punk—for which she was first known—but also casts the prose of her memoirs into the spoken word of an instantly lovable persona. The asides in “Just Kids” make it plain that her momentum took her in a different direction than the trajectory of her beloved Robert. She makes it plainer still that their relationships with the Warhol Gang were not of immediate interest. Although she herself eventually turned away from drugs, she possessed a great empathy for those who did not, and which washes over into her poetry.

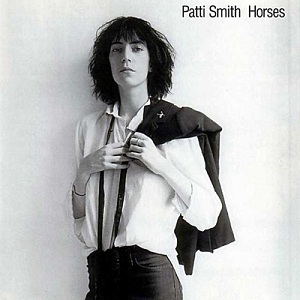

Over time she got to know everyone on the scene, the younger ones—the punk musicians, known and unknown, dramatist Sam Shepard (with whom she had a dalliance), and the rock stars Joplin and Hendrix and Bob Dylan—and the older bohemians as well: William Burroughs and Allen Ginsburg (the latter at first mistaking her for a pretty-faced boy). Gregory Corso, Viva, Holly Woodlawn, Salvador Dali—so many in-crowd names are dropped, it’s a wonder that she manages to do so with that lovable casual aplomb of hers. By the end of the 70’s decade, it wasn’t just the Mapplethorpe photo of her that was “iconic”—the one on her mighty first album “Horses”—it was Patti Smith herself.

Over time she got to know everyone on the scene, the younger ones—the punk musicians, known and unknown, dramatist Sam Shepard (with whom she had a dalliance), and the rock stars Joplin and Hendrix and Bob Dylan—and the older bohemians as well: William Burroughs and Allen Ginsburg (the latter at first mistaking her for a pretty-faced boy). Gregory Corso, Viva, Holly Woodlawn, Salvador Dali—so many in-crowd names are dropped, it’s a wonder that she manages to do so with that lovable casual aplomb of hers. By the end of the 70’s decade, it wasn’t just the Mapplethorpe photo of her that was “iconic”—the one on her mighty first album “Horses”—it was Patti Smith herself.

“Just Kids” ends there, with a homage to Robert’s last days. There’s really not much about her punk grrrl persona in the book. And so at this point I’m left wondering about the Patti Smith of later years, because the “M Train” references and refrains have not been resolved. And the Patti Smith of earlier years? Well, a bit of Wikipedia reveals that Smith—female punk rocker extraordinaire for about 6 years—retires from the New York scene by 1980.

For roughly the next 15 years, during her marriage to guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, she raises a family in Detroit. No doubt she was reading her beloved mystic poet William Blake, and the street urchin poets she idolizes (Rimbaud, Genet), and other books aplenty, and likely polishing her own visionary view of poetry as well. Following Fred’s death in the early 90’s she makes a comeback, and seems a perfect match for the times: poet-slash-performance-artist, a somewhat fabled one by then. She arrives with a reputation that had only grown in her absence, the once-upon-a-time punk singer AND poet rapper. She did, in the interim, publish a book of poems as well, and an album.

The Music

At this point I foolishly take another crack at “M Train”—and still not clicking with it. In that meandering back-and-forth thoughtfulness of hers I am still lost. I know nothing of this person other than facts— nothing of this woman, this artiste, this singer, this celebrity. I decide that what’s missing is a familiarity with her work—since, after all, what I know of her is really second hand. Why else would she have won so many awards? It is not memoirs alone that engenders an audience.

I must again burst backwards in time. I pick out a smallish book of her poetry, off the shelf, “Auguries of Innocence” (2005), and read the whole thing sitting cross-legged on the floor at Barnes and Noble. It is . . . poetry . . . I think . . . about something, I’m not sure. I pick up a late-life covers album, “twelve” (2007). I watch a film about the person and the phenom, “Patti Smith: Dream of Life” (2008). I listen to another album “Peace and Noise” (1997)—which has some originals, and is ably sung, singed with pain. I go back to the pre-Sonic days on her third album, “Easter.” I head even further back into YouTube Land, watch some scratchy videos. I listen to the entire “Horses” album. I marvel at the Mapplethorpe photo of her, back in the day of album covers.

Patti Smith was quite the phenom. She brought her gift for spontaneous poetry and fever for the stage. She hounds the microphone with Jagger-esque panache, and sings with a longing, Dylan-esque croon. Her feel for reinterpreting and covering classic hits (“Gloria”, “My Generation”) was wildly successful. A great back-in-the-day film of her singing “G-L-O-R-I-A Gloria” from that first album—the nimble and haughty and dark-eyed Smith prancing and bantering between the musicians of her band, their on-stage call-and-response, throwing her effervescent bad girlishness at the audience, hooting, screeching, banging on a guitar she can’t even play. Oh, and feeling the adoration. Mustn’t forget. The performance is everything. The audience is everything. Solid and head-banging.

I had some friends in those days who read Rolling Stone, so I wasn’t without feelers. But I only remember one, David King, who once said to me, “Have you heard about this Patti Smith Group”? Well David, I missed the train. In her lusty baritone, her thin, androgynous look of loose-fitting t-shirts, jeans, leather-jacket, her in-your-face song titles like “Piss Factory” and lyrics like “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine”—Patti Smith had arrived—and without me.

She seems perfect for her time, sleek and curiously bisexual. She was appropriately jaded. And she added this: stream-of-consciousness poetry. If Ginsberg popularized coffee-house performance poetry, I know of no other artist besides Patti Smith who took it to the rock stage, apparently with huge success—her poetic chants are listenable if puzzling—once compared by a critic to Sufi poetry—sometimes called “raps” in that pre-rap era—and perhaps she didn’t so much popularize it as scandalize it. Another critic called it “startling freewheel poetry”—but it was perfectly natural, I discovered, and rose from the deep well of her intimacy with the poems of William Blake.

I picked out “Easter” (1978) to spend a day with—because this was a more mature effort, a comeback album after a disappointing interim release—recorded a year after her well-known (to some) brush with death in 1977, falling from a stage in Tampa and breaking her neck. The album featured an odd top-40 hit, “Because the Night,” written for her by Bruce Springsteen. But none of this is in anyway real to me. As I said earlier I do remember only the hit song. Her old, original band on the record is still just okay, but has a full sound on the studio recording, tight in a raucous way—and, it must be said, perfectly suited to Smith’s moody songs and her preference for head-banging rock. But this is not “punk” in the usual sense—and I’m no rock critic, nor wish to be (to me most rock writing is overwritten and churlish, all confetti and word mush) but I gathered in just enough of it to get a feel for the reputation of Ms. Smith.

The thing I take away is her uniqueness in the moment. In this regard, “Easter” does not disappoint. It  contains “Babelogue”, a sample of her ranting as well. During “Rock ‘n’ Roll Nigger” (yes, you got that) she raps out the names of outsiders—the paint-drizzling abstract expressionist Jackson Pollack among others—in a song that peels off the names of misfits and calls them “outside of society”—in league with “black sheep, whores and niggers” as she says, not cynically. This is work very much like Ginsberg’s, an anarchist combination of defiance and freedom and righteous indignation, but done with a rock band that, actually, makes the improvisational poetry kind of exciting for a new audience.

contains “Babelogue”, a sample of her ranting as well. During “Rock ‘n’ Roll Nigger” (yes, you got that) she raps out the names of outsiders—the paint-drizzling abstract expressionist Jackson Pollack among others—in a song that peels off the names of misfits and calls them “outside of society”—in league with “black sheep, whores and niggers” as she says, not cynically. This is work very much like Ginsberg’s, an anarchist combination of defiance and freedom and righteous indignation, but done with a rock band that, actually, makes the improvisational poetry kind of exciting for a new audience.

Dialing ahead 30 years

By the turn of the century, Patti Smith has come full-circle, having lived a full life—back on stage, not big-time, but back, definitely back. In the early 2000’s we find her fronting for Bob Dylan. An amazing resurrection, really. Articles come out. Audiences revive. The “The Patti Smith Group”—pretty much the same band with Lenny Kaye—has improved a bit, now finally sporting a young 20-something named Oliver Ray, who is not a lead guitarist exactly but tickling solos here and there, throughout most of the songs, and providing a musical burnish that was never there before.

In the movie “Patti Smith: Dream of Life” (2008), we meet Ms. Smith head-on. Thank you, dearest filmmakers! Of course, they really don’t reveal any more about what she is actually doing up there on stage—her covers are bracing, her original songs accessible—but in the POV-like movie we see her revealed as everything else she is, day-to-day, sometimes wistful, often sullen, given to overlong oratory, harangues, piquant philosophical ruminations, and a glowing sense of humor.

But what IS SHE DOING? Alas her precise received wisdom is scarcely broached. In the movie she is seen mostly in her later years, on stage, traveling, joking with some of her same band members—trying, and without success, to play guitar with Sam Shepard—who was a musician as well, back in the day, and with whom she is still friends—she is seen painting and drawing, photographing everything, dabbling in every kind of art, reciting Ginsberg, even toying with some of Mapplethorpe’s ashes from a tiny urn that she keeps with her on her travels.

Maybe Patti Smith is not really great at anything except being Patti Smith. Certainly that appears to be enough. She is unique on the circuit, the essence of a word that once captured the hearts of our own generation: spontaneous. Not unlike Frida Kahlo, an inspiration of hers, she defines “other-worldly” in a way that is both down-to-earth and mystical—deadpan on the outside, roiling with message on the inside.

As with many other artists of mid-century, the prolific Ms. Smith does not easily give up her meaning. If she does indeed have a secret sauce—and it is my opinion that she does—it is esoteric. It was not (at least for me) in her poetry. A second helping of her poetry would require an encryption key. I could not decipher what any of them were about. They are—I will say this—a veritable waterfall of words—not dense exactly but seldom sticking together in the usual sense of direction—appearing to be headed in every direction as a fine mist rises, back-and-forth, churning up-or-down, more a rich pastiche of images, fleeting sights and sounds mixed with dreams, ideas and visual feelings . . . some appear to be on topics of current, contemporary affairs, personal tragedy . . . . References to Genet and Blake and others reinforce the feeling that something spiritual is up. Heck, and even fairies are made mention.

Patti Smith “M Train” (2015)

The punks have now been mainstreamed, lauded and canonized. Just last week in Los Angeles, a Mapplethorpe retrospective opened simultaneously at two museums: the J. Paul Getty and the L.A. County. This week, a companion documentary film “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures” will debut on HBO. It is said that several punk grrrls have memoirs on the way—thanks in large part to “Just Kids.” Can tribute bands be far behind?

Paul Getty and the L.A. County. This week, a companion documentary film “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures” will debut on HBO. It is said that several punk grrrls have memoirs on the way—thanks in large part to “Just Kids.” Can tribute bands be far behind?

I am back to reading “M Train”—and finding, now, that I can at last read it and get a little of what she is after. Smith, an incurable romantic, has expanded her repertoire and her color and her expressiveness as a writer. Yes, she is back to dropping names, Blake and Rimbaud and Genet, in particular, and various other literary and artistic loves abound—a little THINLY sometimes, but COYLY nonetheless—leaving it up to everyone else as to whether she too is indeed a visionary. But, as she says in the movie, and practically flaunts in the book, spirits of the past flow through her. She is haunted by her books and her reading. She weaves her thoughts and experiences into and around visits to the little Cafe ‘Ino near her apartment, and takes literary flight from there, allowing us to accompany her on trips and experiences and little thought-experiments that have transformed her.

Patti Smith won a National Book Award for “Just Kids”. Here’s what I’ll say about “M Train.” The texture-less prose of “Just Kids” has improved mightily. And now she has an intriguing meditative style. Having unearthed her many talents, I know her a little better, yes. Her literary voice has that same mournful quality that pervades the best of her songs. Since so many of her intimates have died along the way, she finds solace in their words and closeness to their spirits. Shy from an early age—a ponderer and a medium for the fault lines of history—in this book she looks backwards as well: she visits graves and tombs and hotel rooms the world over, and melts before a number of physical talismans—the prison cell of Jean Genet, the desk of her father, the chair of Roberto Bolano. Perhaps for the modern reader she touches upon the lives of famous artists and intellectuals of a tradition of her choosing. A good bit of the narrative is a paean to her former husband.

But her stream-of-conscious poetic impulse can lead to a morass of oddly-inspired thoughts. A meditation on Haruki Murakami’s mysterious contemporary novel “Wind-Up Bird” is somehow and very modernly mixed with idle thoughts on “CSI: Miami” which she binge-watches. Real, true—okay, but not terribly engaging. In one of her better passages, she has a notion that her desk itself is a conduit to other lives, other experiences, and this she weaves into several other of her own touchstones, previously expounded-upon:

I taped one of the photographs of the stone table above my desk. Despite its simplicity I thought it innately powerful, a conduit transporting me back to Jena. The table was indeed a valuable element for comprehending the concept of portal-hopping. I was certain that if two friends laid their hands upon it, like a Ouija board, it would be possible for them to be enveloped In the atmosphere of Schiller at his twilight, and Goethe in his prime.

All doors are open to the believer. It is the lesson of the Samaritan woman at the well. In my sleepy state it occurred to me that if the well was a portal out, there must also be a portal in. There must be a thousand and one ways to find it. I should be happy with the one. I might be possible to pass through the Orphic mirror like the drunken poet Cegeste in Cocteau’s Orphee. But I did not wish to pass through mirrors, nor quantum tunnel walls, or bore my way into the mind of the writer.

In the end it was Murakami himself who provided me with an unobtrusive solution. The narrator in “Wind-Up Bird” accomplished moving through the well into the hallway of an indefinable hotel by visualizing himself swimming, akin to his happiest moments. As Peter Pan instructed Wendy and her brothers in order to fly: Think happy thoughts. —“M Train”, p.104

Not bad, but can’t say I’m crazy about Patti Smith the writer. As a musician she seems more of a folkie than a rocker now, but gosh, there’s still not a box you can put her in. Dabbler and dervish, rapper and poet, she’s completely unafraid to strike out into any untried form of artistic expression whether or not she has a handle on it. To my ear, it is her performance poetry and the early punk rock that defines the beauty and the audacity of her. That was her electric kool-aid: accessible, rhythmic, harsh, revealing, sexy. A song or two on each of her albums really does resonate “greatness”—what some might call performance genius—acting out a role that thrills a crowd.

Ms. Smith turns 70 this year. In videos, interviews and on stage, her affecting personal qualities still do emerge, as they did in the beginning. “M Train” is probably just another turn on the many side roads of her life. Politically she is correct, in the folk tradition. She leans into the wind, sometimes shouting still—but seems always to pull back into that shy-girl on-stage slouch that fans know so well. She is gigging and touring, sometimes as a warm up for Bob Dylan. She has made quite a career of her life. The self-described “Rock n’ Roll Nigger” of the 70’s is this decade’s toast of the New York underground—and has a National Book Award to top it off. Who else in punk rock can say that?

Ms. Smith turns 70 this year. In videos, interviews and on stage, her affecting personal qualities still do emerge, as they did in the beginning. “M Train” is probably just another turn on the many side roads of her life. Politically she is correct, in the folk tradition. She leans into the wind, sometimes shouting still—but seems always to pull back into that shy-girl on-stage slouch that fans know so well. She is gigging and touring, sometimes as a warm up for Bob Dylan. She has made quite a career of her life. The self-described “Rock n’ Roll Nigger” of the 70’s is this decade’s toast of the New York underground—and has a National Book Award to top it off. Who else in punk rock can say that?

Okay, then, last question: does Smith deserve to be considered Legendary Literati of our 21st Century? Probably not, but I kinda think, after trying my best to figure what she is really doing up there on stage, we may yet live to see this elder-statesgrrl become the female Ginsberg-Dali of our new day.

Leave a Reply