Alternate History 101

Today our world is abuzz with talk of incipient fascism. Some would say the concern, trending not only here in America but the world over, is exaggerated. For others, evidence abounds. Many millions in Europe and America yearn for a strongman that will “take their country back.” Some voters dismiss the possibility; others blame social and economic problems on minority demands out of sync with the traditions of our homeland.

Today our world is abuzz with talk of incipient fascism. Some would say the concern, trending not only here in America but the world over, is exaggerated. For others, evidence abounds. Many millions in Europe and America yearn for a strongman that will “take their country back.” Some voters dismiss the possibility; others blame social and economic problems on minority demands out of sync with the traditions of our homeland.

Is “fascism” simply the rise of a demagogue in a nation addicted to slanted news and racially-tinged resentments? Is it the emergence of lying as a form of persuasion? How do people come to accept a dangerously ignorant leader and allow him to dominate national dialog so rapidly and with such bombastic authority?

The answer may reside in our psyches. For at the very moment that a viciously resentful and vulgar new U.S. President rants that his nation is teetering toward catastrophe, an even bigger danger lurks: the authoritarian impulse. It has arisen not just in a leader but in ourselves, in the national conversation. Fear-mongering, bullies, racists, and all manner of hate-based agendas sprout like weeds. Repugnant symbols are proudly held in front of cameras. Counter movements are suddenly called for.

No, no, the tut-tutters maintain, this is all blown out of proportion! Actor Meryl Streep’s recent announcement that “I feel compelled to stand up in the face of Trump’s troll attacks and his armies of brown shirts” is shrugged off as either melodramatic or worse. Surely, this is not real fascism. Surely there is a middle ground between such a dire assessment of today’s social media and the fact that people just want to walk back all the extremism erupting around the world.

Last year the Gallup Poll confirmed that only 32% of the population now believes that the news media is trustworthy. Citizens and historians have drawn striking parallels from our own presidential predicament to the tactical propaganda of known dictators. Alongside a notable stench of “acceptable lies” flooding our nation, there has also arisen a psychology of appeasement. A recent CBS News poll conducted by YouGov shows the extent to which Trump “believers” (roughly 20% of the population) might in fact display an affinity for fascist-style behavior. One of the poll’s conclusions is jarring:

They’re overwhelmingly for the travel ban (at 91 percent support) and two-thirds would also be for a religious test for those seeking entry. Most would have the President ignore the courts if the courts overturn the ban.

Naysayers, I see you are still shaking your heads. Why all the fuss? you say. After all, there are the courts. And some journalists who won’t put up with it, and some politicians too. Doubting historians. Investors hedging their bets. Concentration camps? No way. Brown Shirts? You have to be kidding. These things could never happen in America. Intensely patriotic men and women simply voted for a change, a big change, and are hoping for the best. And what authoritarian agenda are you talking about anyway? It seems impossible to believe that Ecclesiasticals and Klansmen will be one day holding hands on the parade ground of ethnic cleansing.

The worried among us say the demagogue encourages unity with his fulminations. Trump’s barrage of tweets helps the world forget his previous lies and evasions just long enough for him to move on to the next. In so doing he is able to establish credibility and paint an alternative landscape of miscreant facts and blatant misstatements. Without our shrugging it all off, without the acquiescence of many millions of Americans, he wouldn’t stand a chance.

Finally … there are those who say it has already begun. Those people sense the worst, feeling that all it takes in this culture of heightened fear is just one more massive disaster—some sort of serious terrorism perhaps. Don’t forget Berlin, 1933: a shocking arson attack on the national parliament turned the tide. Hitler stepped up to the challenge. His “emergency powers” were not long in coming.

Alternate HistorY

Let’s unsettle matters even more. Let’s take a look at history as unchangeable except for one single event in the past that has been altered—not by intervention, but by some logically flipped switch. Pick a known set of circumstances that could easily have been otherwise. Is it reasonable, then, to assume that an assassination, or a war lost, or an election won could be a game-changer?

Altering or re-framing of history is actually a genre of speculative fiction called Alternate History—or, alternatively, Counterfactual History. And take my word for it, the two genres sometimes cross boundaries. Some alternate histories contain fantasy or science fiction, employing devices, say, to change the past from the present. Others take a more traditional approach, narratives that presume a blip in history’s timeline. A writer steps in to create an alternative universe from the outcome.

The old What if. Here follow some examples from a list of titles on the “Sidewise Award” site for alternate history:

What if—Hitler was never born?

What if—War broke out during the Cuban Missile Crisis?

What if—Kennedy survived the assassination attempt?

What if—The Spanish Armada was victorious and Queen Isabella came to rule England in the time of Shakespeare?

Of course there is no guarantee we will learn anything from the past—that stubborn thing we are otherwise condemned to repeat. In fact, the impulse to imagine alternatives is always eating away at us. It is our mind’s tendency to wander that brings us to acknowledge the odds of the alternative, such as when, upon a slow Saturday afternoon, we stop to ponder, privately perhaps, and for the briefest moment, a road not taken.

Such an imaginative venture presupposes a more fundamental question about civilization: what is, and is not, necessary. Not all of it may be necessary. At least until the last page.

Philip K. Dick “The Man in the High Castle” (1962)

The year is 1962, precisely 15 years after Capitulation Day. Exactly why the world is divided between Germany and Japan at this moment is not yet revealed, but Mr. R. Childan, an antiquities dealer at American Artistic Handicrafts in San Francisco is anxiously preparing for a visit from his loyal customer Nobusuki Tagomi, a powerful bureaucrat at the Trade Mission.

The year is 1962, precisely 15 years after Capitulation Day. Exactly why the world is divided between Germany and Japan at this moment is not yet revealed, but Mr. R. Childan, an antiquities dealer at American Artistic Handicrafts in San Francisco is anxiously preparing for a visit from his loyal customer Nobusuki Tagomi, a powerful bureaucrat at the Trade Mission.

Mr. Tagomi needs a gift for a visiting dignitary, a Mr. Baynes. Tagomi has requested a rare Civil War recruiting poster which Childan cannot obtain. Childan, who often anguishes over the idiosyncrasies of his Japanese overseers, has no idea what else to propose. A mirror from the 1812 war? An ice cream maker circa 1900? An original Victrola cabinet? He at last presents Tagomi with a 19th century Colt .44. Tagomi is delighted, but says he needs ten of them.

There is a lot of tongue-in-cheek at play here, as we have come to expect from science fiction writers. But the story itself is bleak. That Childan is a bigot, and seems never able to fully satisfy his wealthy clients, is a recurring theme. That he was not originally a discerning art dealer does not go unnoticed either. His business, which started out as a second-hand shop, was invigorated by the Japanese invasion.

In fact Childan’s business has done rather well since the establishment of the Pacific States of America (PSA), largely because the wealthy Japanese have developed a “craze for Americana.” But he has trouble hiding his prejudiced inclinations too. There are “reds” (American Indians) and “blacks” (mostly slaves) and the “Jews, gypsies and Bible students” have been mostly bundled off to elsewhere. In Europe the Slavs have been successfully relocated to Asian Steppes, “back to riding yaks and hunting with bow and arrow.”

But Childan represents average Americans who, despite being vassals, consider themselves mostly better off than before. To the east, the Rocky Mountain States (RMS) form a kind of free, unfettered state, and as a result are a somewhat unruly territory. Further east, comprising the remaining continental states, stands the Reich’s far more disciplined USA. The Germans have succeeded in conquering much more of the world than the Japanese. Their engineering prowess has resulted in the adaptation of rockets for extremely fast air travel, exploration of space and the planets, even the draining of the Mediterranean to establish “Project Farmland.” In this alternate history, only Germany holds the keys to nuclear weapons.

Of course not all is going swimmingly. Hitler has stepped down, and is dying of syphilis. The much-vaunted German pride and work ethic has over time rusted into internecine infighting, with many divisions among the previously united rulers at each other’s throats. Africa has spiraled out of control.

Admittedly history itself is a little warped. In our real-life timeline, on February 13, 1933, FDR was actually the intended target of an assassination attempt while riding in his open-air convertible in Miami. In Dick’s novel, FDR was assassinated.

Admittedly history itself is a little warped. In our real-life timeline, on February 13, 1933, FDR was actually the intended target of an assassination attempt while riding in his open-air convertible in Miami. In Dick’s novel, FDR was assassinated.

And for that reason the economy never fully recovered, and the United States remained isolationist, and the Americans never joined with the British against the German invasion or dove headlong into the Japanese wars either. Even 15 years after Capitulation Day, extermination camps still do their evil work, but widespread corruption complicates the process. Jews go underground, and go to great extremes to change their names and identities.

Juliana Frink has fled the PSA for the RMS. She lives in Colorado, we find her in search of something meaningful in her life, not least of which is a good man. In time she falls in love with an Italian émigré, Joe, who had been a fighter for Mussolini against the British in Northern Africa. And Juliana happens across a rather curious book in Joe’s apartment.

“The Grasshopper Lies Heavy” by Hawthorne Abendsen is a book-within-a-book, a fictional alternate history within Dick’s own fictional alternate history. In “High Castle,” which we are reading, FDR was assassinated. In “Grasshopper,” which his characters are reading, FDR was not assassinated. As Dick’s novel becomes a wonder for us, Abendsen’s novel becomes a wonder for the characters in Dick’s novel. It is as if each of them is sorting out the strange logic of alternate facts gathered on the page. It is as if they are looking out at our world from the prison of their own.

As you might expect, most of the characters in “High Castle” disagree with some aspect of Abendsen’s conjectures. How could it be that America’s victory would be better than Germany’s? Julianna’s Italian heart-throb Joe has his own opinion.

“They [the Axis Powers] saved the world from Communism. We’d be living under Red rule now, if it wasn’t for Germany. We’d be worse off.” - Chap. 6

Juliana brings a fierce curiosity not seen in the other characters. She is fascinated by the “Grasshopper.” She reads nonstop, and gathers further insight of the plot details from Joe, a former soldier with Mussolini’s infamous Italian General Graziani. But Joe is dismissive. Speaking about the book’s conclusions, he says:

Sure the U.S.A. expands economically after winning the war over Japan, because it’s got that huge market in Asia that it’s wrested from the Japs. But that’s not enough; that’s got no spirituality. Not that the British have any. They’re both plutocracies, rule by the rich. If they had won, all they have thought about was making more money, the upper class. Abendsen, he’s wrong; there would be no social reform, no welfare public work plans—the Anglo-Saxon plutocrats wouldn’t have permitted it. - Chap. 10

Normally the only book that Juliana carries with her is the “I Ching” which everyone else consults as well. But Juliana’s curiosity is getting the best of her. Joe is no Nazi sympathizer, only a practical man. He might despise the Nazi regime and its culture (he makes fun of the inane New York musicals that trot out such things as a history of Gothic tribes) but he has made his peace with it.

A good many other characters and plot twists ensue, but at long last we hear from Tagomi’s expected guest, Mr. Baynes. He has arrived in San Francisco nonstop from Berlin on one of those Lufthansa rockets. He is on a personal and secret mission. He reveals that his real identity is Captain R. Wegener of the Reich’s Naval Counter-Intelligence. He tells Tagomi that the Germans have a horrifying plan that goes by a deceptively innocent ID:

“Dandelion,” Mr. Baynes said, “consists of an incident on the border between RMS. and the US. US troops will be attacked and will retaliate by crossing the border and engaging the regular RMS troops stationed nearby. … The basic purpose of Operation Dandelion is an enormous nuclear attack on the Home Islands, without advance warning of any kind.” - Chap. 12

The “Home Islands” are the Japanese islands, but up to now the Japanese have never personally experienced the horror. Hermann Goring, who has recently ascended to power, is said to stand behind the plot. The only hope for Baynes is to convince Japan, return to Germany, and hope that his own allegiances, shared by a certain SS General Reinhard Heydrich, will allow him to live and continue the fight against the Goring administration from within.

Overall the plot is a crazy quilt of back-stabbing, corruption, secret vendettas and all manner of hooliganism which appears to the characters themselves as normal operating procedure. By the end of the book we too are dreading what might happen, holding on to a thin shred of hope that something will deter the Germans from making a holocaust of it all.

Author Philip K. Dick

When is Dick at his best? When he dotes on characters eager to fit in—the businessmen and socialites and even the workers who have understandably given in—but contrasting them to the individualists who make a heroic difference. Tabuki of the Japanese mission, and another character from the SS both seem to arrive at a final insight. Baynes, who has revealed the disastrous Dandelion plot, makes the most of his courageous humanity as an insider secretly at war with his own country. And ultimately, there is Juliana, who realizes she MUST locate Abendsen at his “high castle” in the wilderness outside Cheyenne, if for no other reason to seek out this oracle. By the end, she has seen that there really is no oracle, but she has also pretty much given up on throwing her fate to the “I-Ching.”

Philip K. Dick drew a dark and gruesome vision of a possible world based on one event in history. The clever and comic scenes serve to draw us into the realization that real life will not be altogether different—only numbed by the acid of acquiescence, here the underpinning of fascism.

A few years ago Amazon picked up this title for a streaming series on television which I understand is highly rated and still going strong. The intrigues are baffling, horrifying, counter-intuitive—as any good serial narrative must be—but there is that grim depiction of “normal life” as well, wherein the realities of war and racism and Zyklon-B have all but been accepted by those who have stopped fighting. But not all. Some fight on.

Oh, and by the way—the Colt .44? It comes in real handy.

Philip Roth “The Plot Against America” (2004)

It is the summer of 1940. The Republican Convention is underway in Philadelphia and the delegate votes are distributed evenly on the first round, creating a “brokered” convention. Round after round, and still no winner. But for years there had been hopes that the great American icon and reluctant candidate Charles Lindbergh could be drafted for the cause. The once-dashing former air mail pilot was heralded the world over when, in 1927, he successfully undertook the longest transatlantic voyage, New York to Paris, on “The Spirit of St. Louis.” He was a huge hero to many, and was bestowed the Medal of Honor.

It is the summer of 1940. The Republican Convention is underway in Philadelphia and the delegate votes are distributed evenly on the first round, creating a “brokered” convention. Round after round, and still no winner. But for years there had been hopes that the great American icon and reluctant candidate Charles Lindbergh could be drafted for the cause. The once-dashing former air mail pilot was heralded the world over when, in 1927, he successfully undertook the longest transatlantic voyage, New York to Paris, on “The Spirit of St. Louis.” He was a huge hero to many, and was bestowed the Medal of Honor.

On the other end of the political spectrum, Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt had decided to run for an unprecedented third term as President. The Republicans were outraged, but felt they had an advantage. Roosevelt had been nudging and urging Congress to step beyond the country’s isolationism to assist Great Britain in a war that raged on in Europe. People were frightened. Germany had conquered Poland and was poised on Russia’s doorstep. The Nazi Luftwaffe was bombing London. From Italy, Mussolini had taken great swaths of North Africa. In the far east the Empire of Japan had invaded China and was keen on seizing every island in Southeast Asia.

Of course in our recorded history Lindbergh and his wife had left America for England in the mid-1930’s following the kidnapping and death of their baby boy. It is an un-alternative fact that Lindbergh, once in England, also visited Germany several times, even once receiving a medal of heroism, the Service Cross of the German Eagle. On his travels throughout Germany, Lindbergh fell—hook, line and sinker—for the near-mystical Nazi nationalism. He thereafter became an “America Firster” and later its organizational spokesman. It was both his Firsterism and his isolationist political philosophy that made him such an attractive potential candidate for the Republicans to run against Franklin Roosevelt. He was often mentioned as a viable candidate, but never seriously taking up the challenge.

Of course in our recorded history Lindbergh and his wife had left America for England in the mid-1930’s following the kidnapping and death of their baby boy. It is an un-alternative fact that Lindbergh, once in England, also visited Germany several times, even once receiving a medal of heroism, the Service Cross of the German Eagle. On his travels throughout Germany, Lindbergh fell—hook, line and sinker—for the near-mystical Nazi nationalism. He thereafter became an “America Firster” and later its organizational spokesman. It was both his Firsterism and his isolationist political philosophy that made him such an attractive potential candidate for the Republicans to run against Franklin Roosevelt. He was often mentioned as a viable candidate, but never seriously taking up the challenge.

When Lindbergh returned to the U.S., though, he toured as a Firster and spoke out against an American war with Germany. He warned of a Jewish influence in “the press, and the radio, and the government”—media was not yet a word—and advised Jews to stand with America, not with their relatives or their sentimental leanings to the European nations.

So here’s where history becomes warped in earnest. In Roth’s telling, the Republican Convention of 1940 eventually drafted—yes—Lindbergh. Given advance notice, the former pilot flew to Philadelphia in his own plane, and waltzed into the convention to standing ovation lasting 30 glorious minutes. Lindbergh was no orator. He was a simple man who loved flying. He gave the shortest speech ever recorded at a political convention. He continued to do so during throughout the campaign.

Lindbergh took as his slogan “Vote for Lindbergh or Vote for War”. Since Roosevelt had come to believe that America must intervene militarily, Lindbergh, in his speeches, would denounce “other people” for exploiting their influence to “lead our country to destruction.” This, in fact, was both the Firster message and the kind of wink-wink Jew baiting that Firsters had actually come to be engaged in.

In June 1941, just six months after Lindbergh’s inauguration, our family drove the three hundred miles to Washington, D.C. to visit the historic sites and the famous government buildings.

The alternative history is in the form of a memoir by the author himself, Philip Roth. He imagines a working-class New Jersey family drama, from his own (real) past. But even if unbelievable, the election had been a surprise to many. It was the polls that were wrong (as Roth writes presciently from over ten years ago). Still, life goes on. Far from a Grimm’s fairy tale of some horrible eventuality, the book charms us with the usual Rothean world of fanciful, ho-hum, daily existence full of family foibles and eccentric characters with the best of intentions.

Phillie, as he is sometimes called by his relatives, is about 8 years old. He is a stamp collector, and adored FDR who himself used to talk about his own collection on the radio during the “Fireside Chats.” Phillie’s collection had many valuable commemorative stamps, including ones featuring Lindbergh. At first nothing appears to be a problem in the political arena, though his father is constantly angry—in fact, can hardly stand to utter the words “President Lindbergh”—and his mother fearful. There were daily rumors wending through the all-Jewish neighborhoods.

Phillie, as he is sometimes called by his relatives, is about 8 years old. He is a stamp collector, and adored FDR who himself used to talk about his own collection on the radio during the “Fireside Chats.” Phillie’s collection had many valuable commemorative stamps, including ones featuring Lindbergh. At first nothing appears to be a problem in the political arena, though his father is constantly angry—in fact, can hardly stand to utter the words “President Lindbergh”—and his mother fearful. There were daily rumors wending through the all-Jewish neighborhoods.

And little things start happening. The family, having checked in at a hotel in Washington, D.C., is summarily denied a room. Phillie’s father Herman demands an answer but is shown the door. In the news, Lindbergh meets with Hitler in Iceland to seal a treaty of peace, the “Iceland Understanding.” Another treaty, the “Hawaii Understanding” settles things with Japan. Upon his return, Lindbergh set out a historic message:

We will join no warring party anywhere on this globe. At the same time we will continue to arm America and train our young men in the armed forces in the use of the most advanced military technology.

Aid to Great Britain approved by the Roosevelt Administration is overturned, leaving Canada as the sole support for England. Lindbergh praises Hitler’s invasion of Russia as a victory against Bolshevism—the greatest threat to our nation and our way of life. It must be destroyed.

On the homeland, though, peace is celebrated by many. Even the Jews begin to believe things won’t be so bad—the president’s anti-Semitism seems to be neutralized by new legislation, in particular the establishment of the OAA, Office of American Absorption. Under the OAA, a youth program called “Just Folks” is established to help young Jewish children conform to the norms of American life by spending summers on farms in the American heartland. Phillie’s aunt Evelyn, educated, a teacher and union member, suddenly gets a job with the OAA.

Of course we find out that Evelyn is the mistress of a collaborator, a well-known Rabbi. She has influenced Phillie’s older brother Sandy, an aspiring artist, to accept a summer outing with the new program, and he loves it, loves the hard work, loves the acceptance of the Gentile farming community. But the Jews are split—even in the Roth family, not everyone agrees. Canada begins to be spoken about as a possible destination. Phillie’s mother takes a job and puts away all her earnings in a Canadian bank for the sole purpose of having cash on a moment’s notice. Their cousin Alvin who lives with them signs on with the Canadian Armed Forces “to fight Hitler” but is severely injured, and loses the lower part of his right leg, and comes home to New Jersey angry and distraught, and creates a moment for the family to reconsider a lot of their own loyalties.

Little Phillie begins to feel his family coming apart. Herman Roth, the father, the most realized character, likes to go to the local “newsreel theater” (an all-news movie house with a 1 hour show of patriotic clips, sports and shorts, and the “March of Time” feature). Herman is beside himself. He hates even the sound of the name “President Lindbergh”. Brother Sandy says “Give it a chance”. Aunt Evelyn has become a bride-to-be and senior government administrator. Phillie and his buddy Earl take to following Gentiles around, spying on them and sharing information.

Yet under that veneer of All-Americanism, the divisive Jewish threat resolves into a horrific normality. Roth makes it plain that the real demon is not Lindbergh, but rather the collaboration of Americans, including some Jews and Rabbis. It wasn’t just the politicians. The German-American Bund becomes a hugely popular club. The bigoted Henry Ford becomes Secretary of the Interior. At the very mention of a political dustup, Lindbergh would get on his plane and fly around the country, stopping in four or five cities a day, campaigning all over again and promulgating the idea of a Citizen Army.

But voices of protest emerge, not least of which is radio personality Walter Winchell, himself a Jew. His programs morph into diatribes against Lindbergh, and before you can say “Hello Mr. and Mrs. America” he is fired outright by the sponsor Jergen’s Lotion. His celebrity news newspaper column in the “New York Daily Mirror” is suspended by William Randolph Hearst.

In the meantime, the ever-irascible Herman Roth gets a letter from his own company.

Dear Mr. Roth: In compliance with a request from Homestead 42, Office of American Absorption, our company is offering relocation opportunities to senior employees like yourself, deemed qualified for inclusion in the OAA’s bold new nationwide initiative.

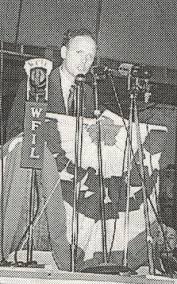

Lindbergh the American Firster

Under the new “Homestead Relocation Program” he and his family will be moved to Danville, Kentucky which his employer, a signatory to the new law, has agreed to. After much hand-wringing, he quits his job as a salesman and takes a job working overnight at his brother Marty’s vegetable market. Marty, Herman and even the kids become persons of interest in some shady FBI investigation.

Winchell sets out on a campaign for the Presidency and is met in every town and city by stalwart foes, the likes of Detroit’s Father Coughlin (a real-life Limbaugh precedent) and the “Christian Front.” Even vigilante groups. Winchell’s firebrand campaign speeches become a danger to public safety. The “Winchell Riots” cause a public uproar, but Winchell soldiers on.

In Buffalo the mayor announces his intention to distribute gas masks to the city’s citizens, and the major of nearby Rochester initiates a bomb shelter program “to protest our residents in the event of a surprise Canadian attack.”

Something called the “Good Neighbor Project” is created to insert Gentiles into the Jewish neighborhoods. The Roths are lucky, while they lost a Jewish family from their first floor rental, they receive into the house an Italian whose loyalties are not so much ethnic as socialistic.

Then, oddly, out of the blue, Lindbergh disappears. He was on his way back to Washington, D.C. and his plane never landed. The hunt is on. Conspiracy theories abound. Martial law is declared throughout the land. War is declared on Canada.

So it is not long, within a year actually, before protests and riots begin to rip apart the illusion of peace in America. The President has been replaced by his “unhinged” V.P. and over a fortnight 122 people, mostly Jews, lose their lives in anti-Semitic riots across the nation. Many others are killed and wounded by the Klan. Soon Winchell is assassinated at a campaign rally. All the big-name Jews are rounded up, including Supreme Court Justice Frankfurter and New York Mayor La Guardia, arrested for collusion in the Lindbergh disappearance. Even Franklin Roosevelt is detained “for his own safety.”

Author Philip Roth

Eventually all of this ends with what we now call a grand conspiracy theory which I will not reveal here, though be assured that Lindbergh and the Germans appear to have some kind of deal in the making. In the last chapter a burgeoning police state is taking shape across the 48 states. It IS thwarted at long last, but not before a permanent fear has settled in.

Roth did not create, or predict, a Trump-like figure. His Lindy is quiet, solemn, a perfect model toy soldier. But a Nazi-sympathizer he was. Indisputably. And an “American Firster.” His leadership was grounded in the appearance of solid gold American values. What Philip Roth does create, convincingly, is the profile of fascist collaborators who continue throughout the book to deny any ill intent or outcome.

By the last chapter, “Perpetual Fear – October 1942” things have pretty much jelled for Americans and their future. And back in real-life, ironically, good old Walter Winchell lost all his good will by siding with Joseph McCarthy and his House Committee on Un-American Activities.

SINCLAIR LEWIS “IT CAN’T HAPPEN HERE” (1935)

This piece was added

March 20, 2017

The year is 1936. The country is mired in financial turmoil. Bleak prospects abound. As with Roth’s vision, the electorate is fascinated not so much by German Nazism but the power and prestige of those European countries that appear to have arisen to greatness from the ashes of the 1920’s. Nationalism, militarism, and the promise of a restored America light up our own presidential campaign like a Fourth of July fireworks extravaganza.

The year is 1936. The country is mired in financial turmoil. Bleak prospects abound. As with Roth’s vision, the electorate is fascinated not so much by German Nazism but the power and prestige of those European countries that appear to have arisen to greatness from the ashes of the 1920’s. Nationalism, militarism, and the promise of a restored America light up our own presidential campaign like a Fourth of July fireworks extravaganza.

Even the town of Fort Beulah, New Hampshire, is all in. FDR is now out of fashion. Senator Buzz Windrip is taking to the radio airwaves, and the community is indeed abuzz with the claims of this outspoken huckster who offers a future of jobs aplenty and cash payouts to ALL working class folks in hardship—all laid out in his “Fifteen Points of Victory for the Forgotten Man.”

In what at first appears to be another unremitting Sinclair Lewis satire, we find our hero, Doremus Jessup—a wizened, wise-cracking editor of the local newspaper “The Daily Informer”—in denial. Jessup is taking the high road. No way, he thinks, that this upstart, blowhard, low-class, bloviating senator from the sticks of southern statehood will ever be elected.

While “It Can’t Happen Here” is not exactly an alternate history (it was written before the fictional events of the novel’s 1936 elections), lately Signet Classics has been working night and day printing softcover copies of this somewhat forgotten classic. Forgotten, as well, by me—and thankfully my trivia buddy, journalist and pop-history specialist Jim Dexter focused my attention on it. The waiting list at my local library had climbed to eleven! Oddly I found a copy on the shelf at Atlanta Vintage Books, complete with crisp white pages and that comforting, new-book smell.

What this magical book gives us is an ever darkening, and ultimately horrific, view of what it might be like to have your country taken over. Gradually—as Lewis notes, “drip-drip-drip”—the country descends into Fascism. Windrip is not at first a maniacal tyrant but a strongman figure modelled on the contemporary Willie Long of Louisiana. Following his election to the Presidency, Windrip begins the necessary propaganda tours needed to both convince and assure the American public that he, and they, must unite against their enemies and prepare for a new and dangerous undertaking. Day by day, one injustice proceeds logically to the next. Judges are replaced under emergency orders. The military grows by leaps and bounds. Local militias, and a paramilitary cadre, here called the “MM” (Minute Men), acquire prestige and near-criminal and violent empowerment with which to “restore peace.” Jews and blacks and illegal immigrants are all targeted.

All this devolves in the context of the normal lives of students and wives and working men and bankers and … yes, even the once-disbelieving editor of the local paper. Eventually, for the crime of a “subversive” editorial, Jessup loses his job and is sent into forced labor. He experiences prison and torture, but discovers along the way a New Underground, which helps to spring him from the camp. He makes for Canada about the same time as a war with Mexico is declared.

The book is long and endearing, but Lewis is a great writer, and Jessup and his friends and family are great characters. The author’s sauntering and homely prose, so typical of his era, combined with his powerfully understated cynicism, had me in his clutches. Events begin ever so quickly to surprise, and then to shock. Detainment turns into prison. Beatings turn into killings. The prisons are so full that concentration camps have to be erected nationwide. The violence Lewis witnessed in his day in Europe is described here in sickening detail, except it is bleeding red-white-and-blue. The last half of the book is undeniably unputdownable.

Author Sinclair Lewis

Illus. by David Levine

If we as a nation have forgotten how dire and dreadful the real world of 1935 seemed at the time, this novel lays it out before us. Should you need a refresher, you will have your wake-up call well before the end of the book. Food lines were just around the corner, poverty on the next doorstep. The government had to hire people for federal work projects. The German Bund was quickly acquiring converts. There was no Social Security for a pension, no Savings and Loans to protect your mortgage, no FDIC to insure your savings. In fact, when Doremus Jessup finally has to gather several thousand in cash for his underground undertaking, he must visit a number of banks in order to withdraw small sums from each—in those days it was the tried-and-true method of self-insuring your own assets.

So if Steve Bannon’s movie “Generation Zero” hasn’t yet horrified you, get a load of Lewis’s chapter excerpts from “Zero Hour”—the novel’s Bible of our new country—the new “Mein Kempf” if you will. Just make sure you have a copy on your living room table when the MMs come a-knockin’. You might also want to bury or burn anything that could be construed as treasonous.

OR, IS IT TOO LATE?

In 1941, Stefan Zweig, an Austrian refugee, novelist, cultural critic and historian of the Weimar era, spoke of the tragic inability of people to accept even the possibility of fascism. Before we leave our novelists, let us go back and revisit a few lines from Zweig’s “The World of Yesterday” as quoted by George Prochnik in “When It’s Too Late to Stop Fascism” The New Yorker Feb. 6, 2017.

The few among writers who had taken the trouble to read Hitler’s book, ridiculed the bombast of his stilted prose instead of occupying themselves with his program.

The big democratic newspapers, instead of warning their readers, reassured them day by day, that the movement would inevitably collapse in no time.

Hitler merely had to utter the word ‘peace’ in a speech to arouse the newspapers to enthusiasm, to make them forget all his past deeds, and desist from asking why, after all, Germany was arming so madly.

Leave a Reply